Interview with artist Melissa Wilkinson

Melissa Wilkinson, originally from Chicago, has been teaching art at Arkansas State University in Jonesboro since 2010. She uses watercolor to give a softness to her images that straddles abstraction and representation. Think of Max Headroom from the 1980’s and a loose cable connection where data are swapped in seemingly random order. Except, Melissa is in full control and wants us to peek inside the curio cabinet. Her work is in collections throughout the country and abroad. More of her work can be seen at her website melissawilkinson.net.

AAS: Melissa, where did you grow up? Are there other artists in your family?

MW: I grew up in a really diverse, bustling area just north of Chicago with two other siblings. Since my mom was a single mom, money and space were tight. Even though my parents were quite conservative and fairly realistic about future prospects, they were very encouraging of my devotion to art. No one in my family could be considered traditionally creative, even though we were all industrious. I think the art thing was entertained out of my enthusiasm, but it was expected that I’d probably become a K-12 art teacher to make ends meet. I’m the only one in my family who really went whole hog into something considered so unrealistic and lofty.

AAS: How did you end up at Arkansas State University?

“Artists have to be continually learning in order to make interesting things and teaching required me to share those lessons.”

MW: I went to Western Illinois University and received a BFA in Painting in 2001 and was awarded my MFA in Painting in 2006 from Southern Illinois University-Carbondale. I ended up at ASU because an offer was made for the tenure track, which was my goal, and they were looking specifically for someone with extensive experience in watercolor.

I started at ASU on the tenure track in 2010 — so up until this month, I’ve served there 11 years. I headed the painting area and taught drawing, watercolor, mural, and painting courses. Since undergrad, I’ve really modeled my life after my own former professors — wanting to serve in that way since it meant so very much to me as a young person. I had a very traditional, observation-based training where our inherited histories were closely examined, and well-crafted objects were the primary objective in practice. I realized the great impact a few words could have at such a pivotal time in a young artist’s life. Professors played a crucial role in asking students to embrace discomfort, confront failure, and see their role as artists as a vital responsibility. I mean “vital responsibility” in that artists are not posh trinket makers for the wealthy, but actual taste makers and mirrors of our shared cultural values. The world has enough strife and wretchedness in it, so why not make the world better than you found it? Enrich things, investigate them, pursue making as if you were charged to do it by a greater power. Artists have to be continually learning in order to make interesting things and teaching required me to share those lessons. Plus, it was requisite that I make art and be successful at it…not just pursue it as a dilettante. I had to model disciplined behaviors and live into the lessons I taught my students out of duty but also job description. It fit for a long while and I felt like I was really making a difference at the end of the day in student's lives.

AAS: You help lead mind/body Art and Yoga Retreats. Would you talk about that and your views on the spirituality of art and creativity?

MW: I’ve recently resigned from my position at Arkansas State University in order to follow and support my wife in a big professional venture. I’ve taken on retreats as a means to continue teaching adults art since I don’t have a teaching position lined up. I’ve partnered with a friend and clinical therapist to offer experiences that engage the ‘wholistic’ self, and not in the granola/wishy-washy/tie-dyed/touchy-feely kind of way that you might imagine. For years, I’ve taught the making and tradition of objects independent of their intention in order to be secular and sensitive. In other words, painting is often stripped of its original intention, more often focusing just on technique. Objects were and are still made to not only transcend beauty but to connect with the divine, to move beyond worldly concerns. This kind of coursework asks students to live into meditation, spiritual reflection, and consider God while drawing from history in making illuminated miniatures or icons. Plus, it’s meditative movement combined with creative stillness at a beautiful location where someone feeds you. Who wouldn’t be into that?

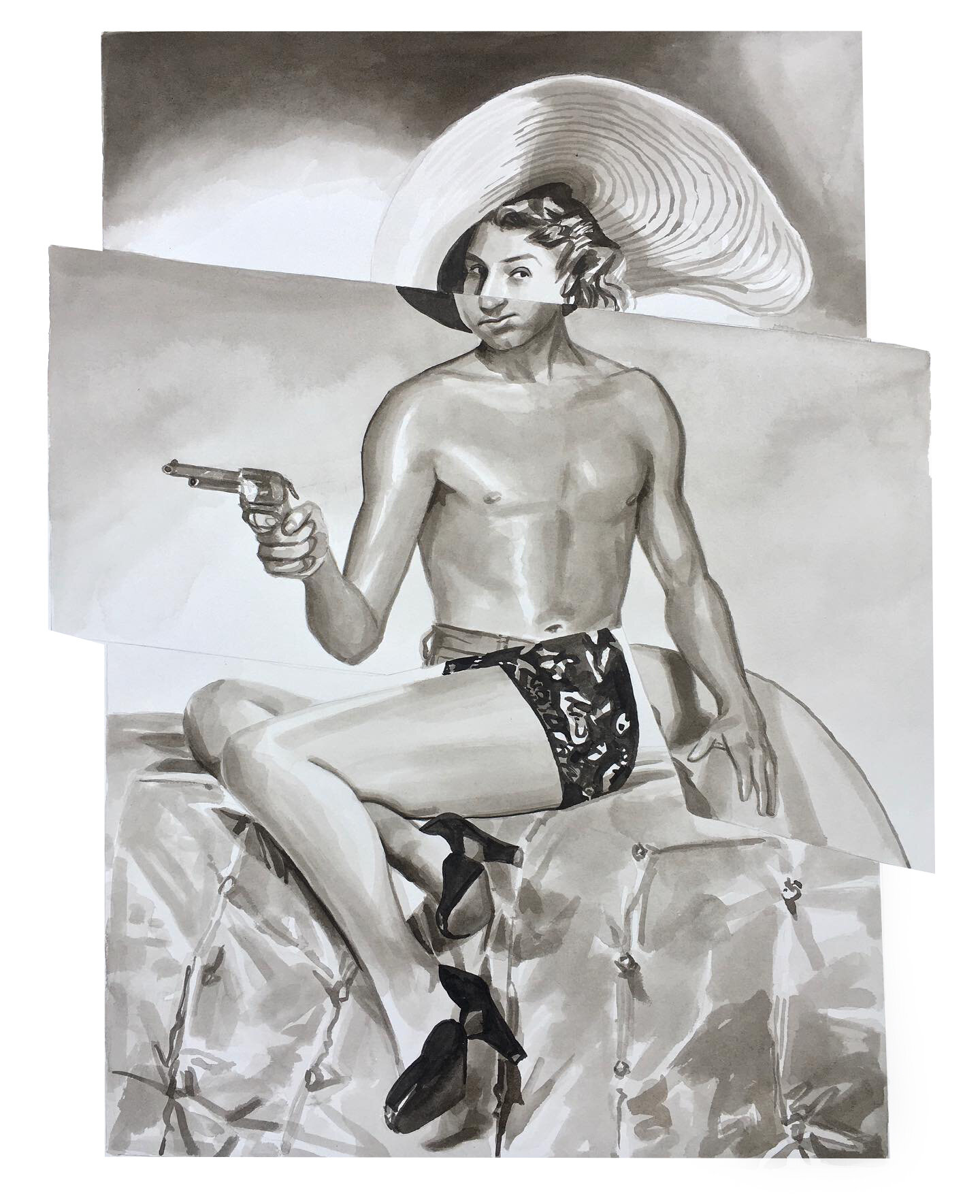

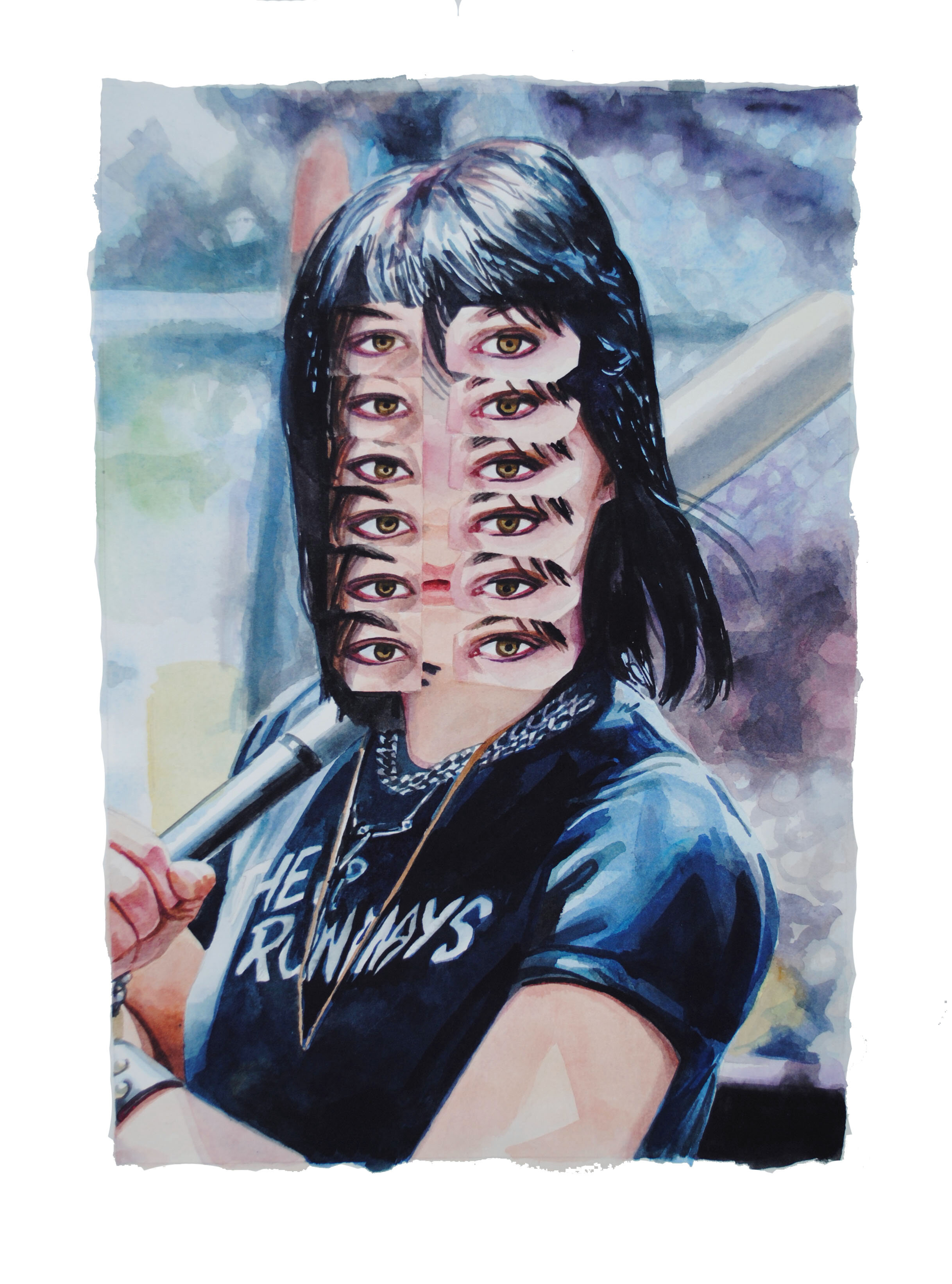

AAS: I love the way you deconstruct, rearrange and reconstruct your ‘subjects’ in provocative, often humorous ways and often centered around gender.

MW: I’m most drawn to painting the figure. I’m an appropriation artist and so I pull from images that are already out there and recreate them into something new. I try and paint it in such a way that seems completely contrived and disconcerting. I’m a lesbian and so my intentions are to investigate the absurdity of emphatic gender conformity in media- specifically in the golden age of Hollywood. Our restrictive inheritance of gender expectations often come directly from these sources in the form of toxic masculinity and the princess narrative… all the things that personally make me want to wretch. I just want to make transgressive paintings that break with the binaries that hold us to unlivable standards. I suppose I’m remaking these figures to make them strange, or “queer” if you prefer. It’s all a remix.

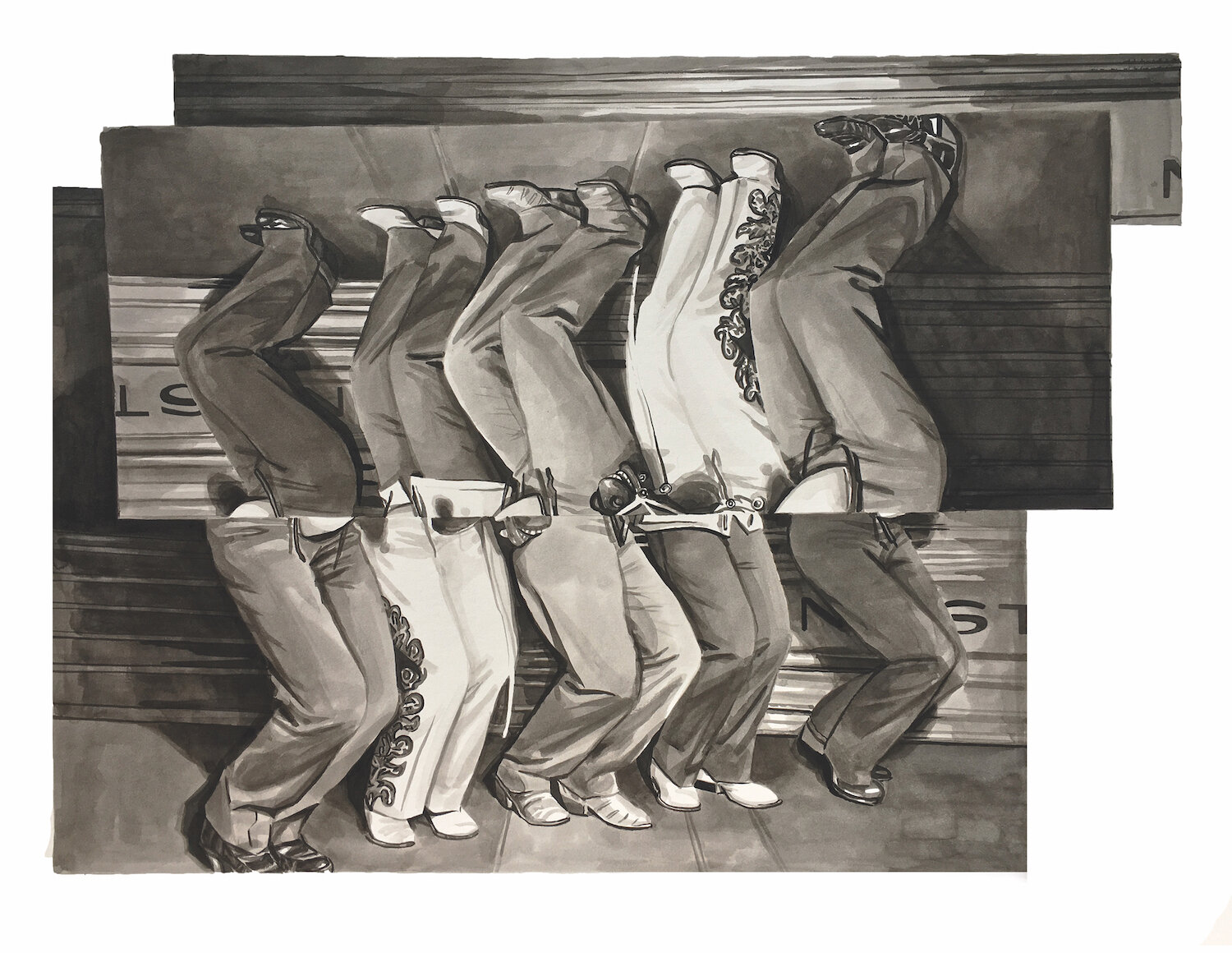

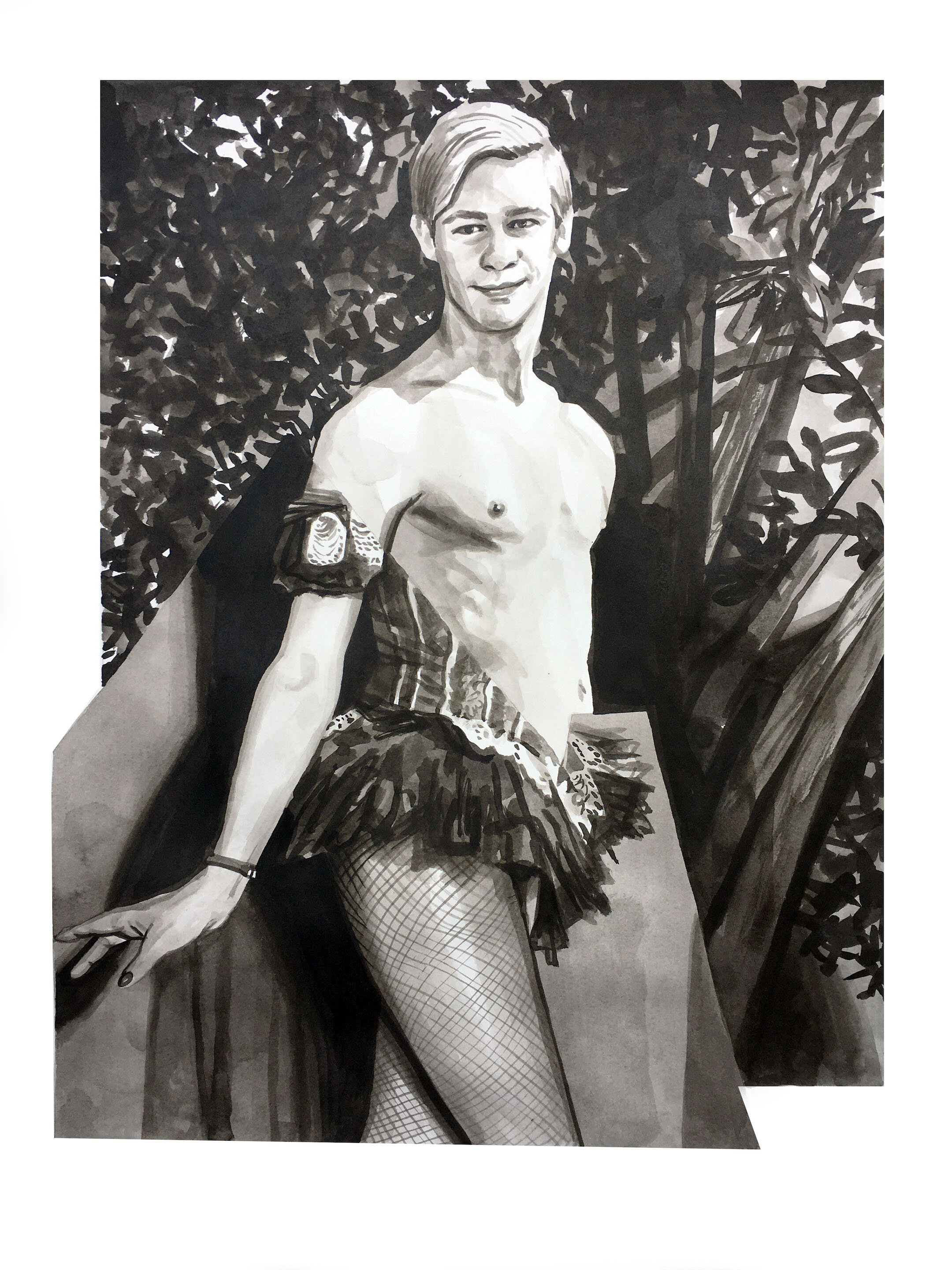

AAS: Your Chimera series is terrific. The Old Hollywood feel in black and white and the quintessential poses – this series must have been a lot of fun. Are you a fan of old movies?

Chimera Series, ink wash on paper, 20” x 16”

MW: Nope. I think old movies are often stiff and rigidly robotic. I generally avoid sitting through them because they bore me to tears. The old buffs are going to hate me for saying that but truthfully, the delivery and lack of complex humanity is the very thing I’m wanting to depict in my paintings. I’m a bit of an asshole in that most of what I paint comes from an intention to question or challenge. I paint these images in a quasi-photorealistic fashion in order to provide a kind of portrait-like devotion, one that attempts beauty on the surface but has no real character…much like a caricature of masculinity and femininity. Francisco Goya painted the Spanish royal family beautifully even though they were horridly ugly. I want you to do the whole “figuring out it’s John Wayne” kind of thing with them but also ask why he suddenly has perfectly arched brows and fishnet stockings on. I’m wanting to ruin the fantasy for straight viewers, I guess.

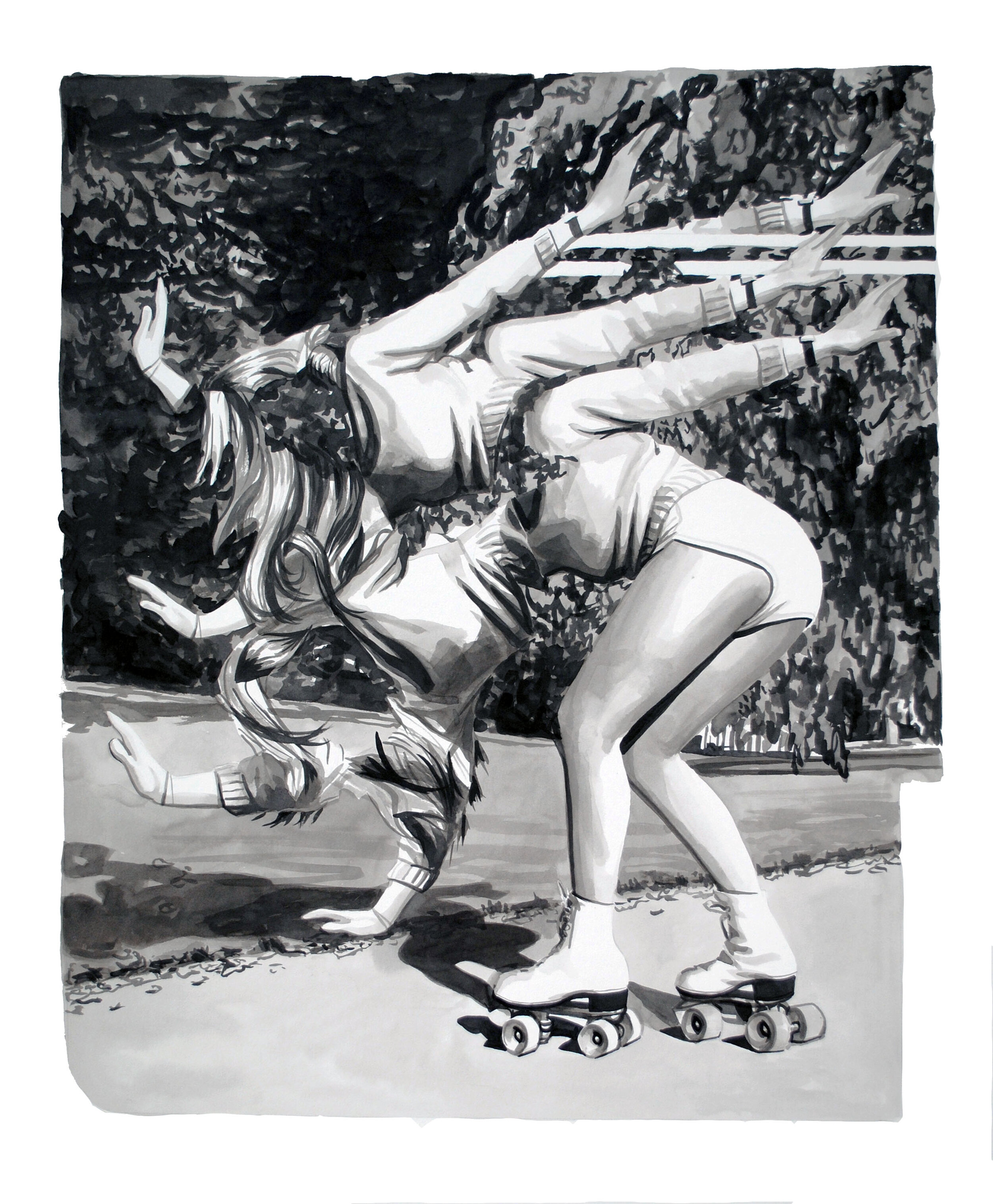

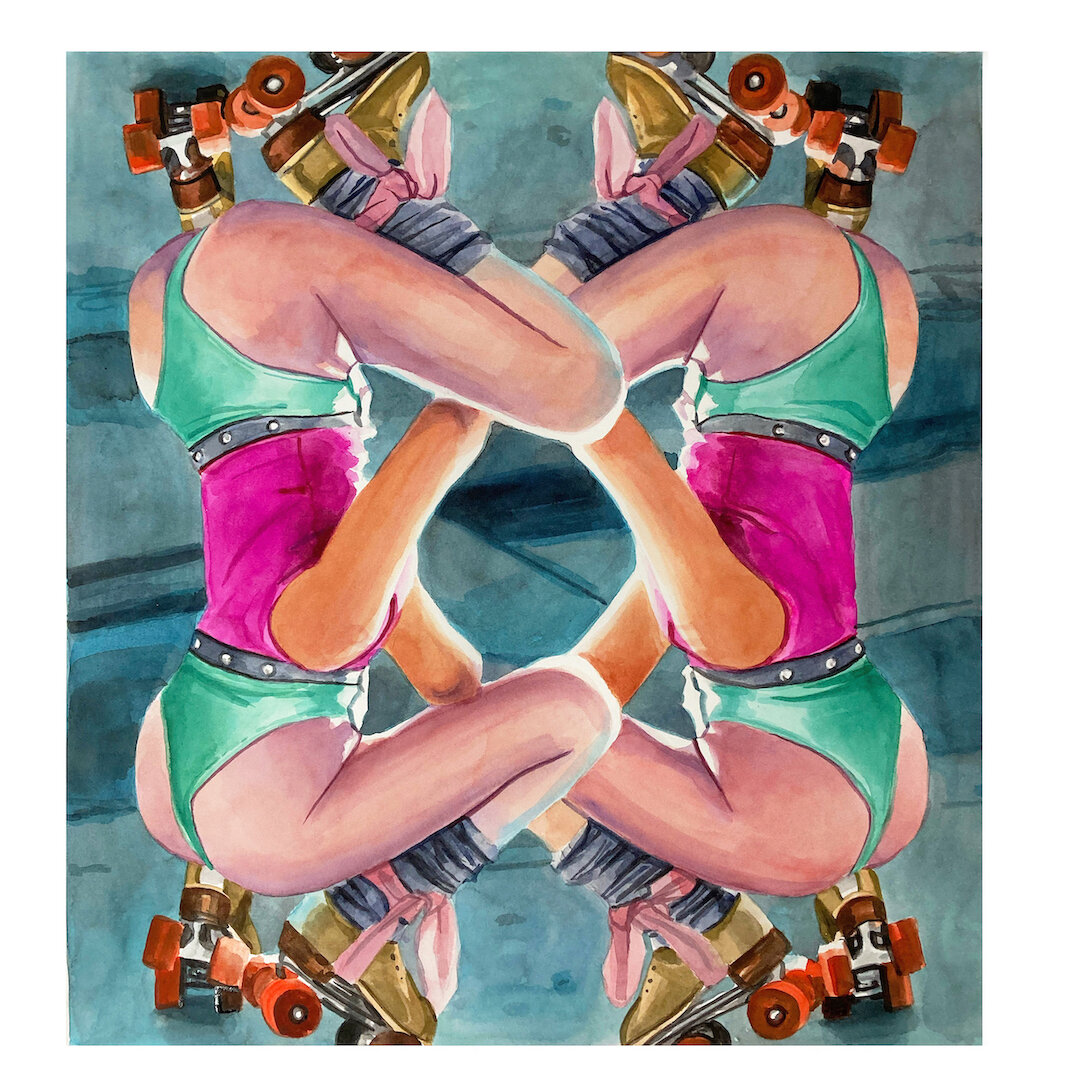

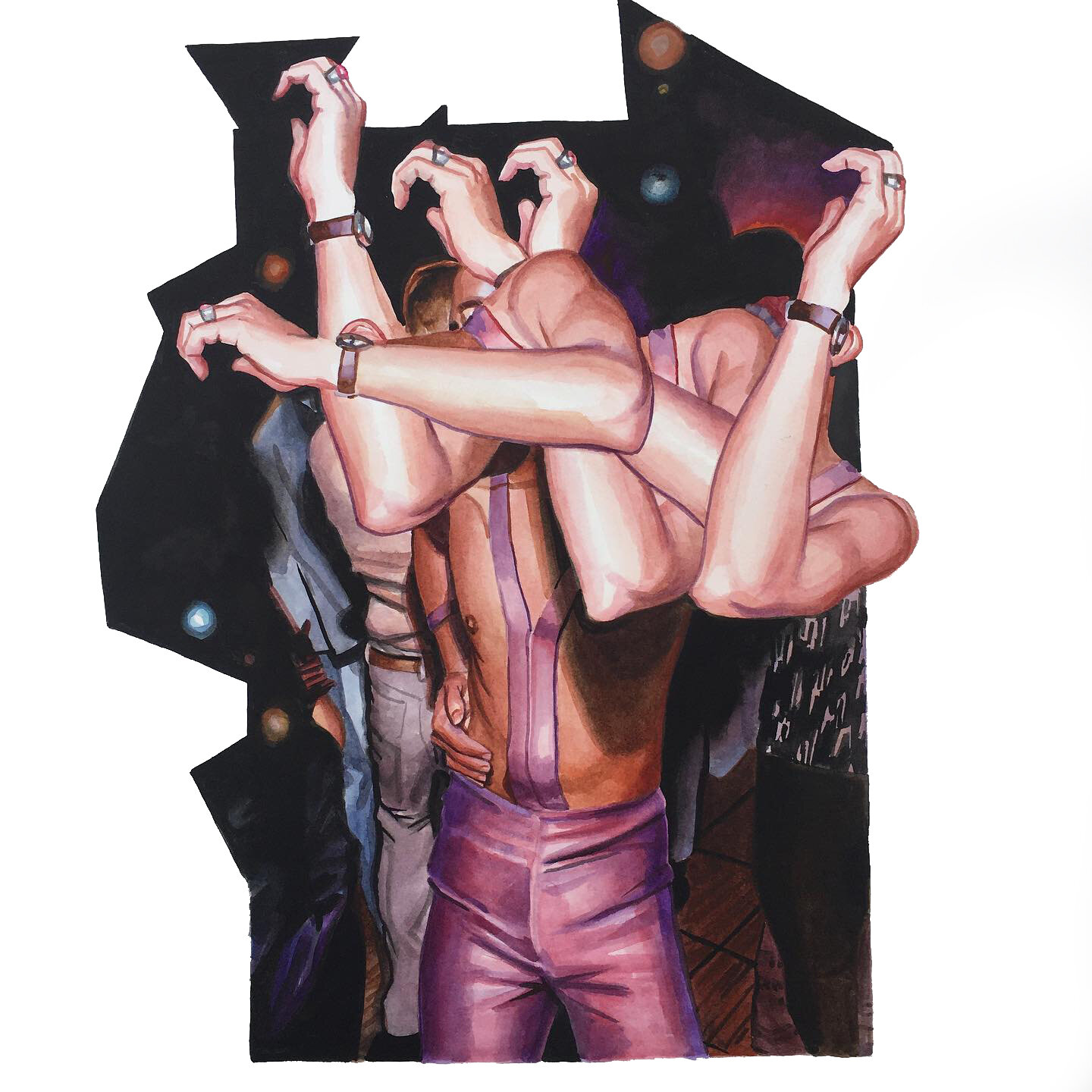

AAS: What about the 70’s and 80’s? In your series Queens you capture the colorful chaos and over the top self-expression of the youth at that time. Would you talk about Just Do It and Swing Kick and what inspired those pieces?

Just Do It, watercolor on paper, 20” x 16”

MW: In Queens I really pulled from my childhood TV and radio influences. Growing up in the 80’s, the films, music and advertising rubbed off on me in the form of acquiring a campy humor. I guess you could say I had a sex saturated television form of parenting. Just Do It and Swing Kick are broken and rearranged to distill what they are really about to me…which is easy sex appeal. Just Do It is a Nike advert with clear overtones of homoeroticism and Kick depicts a roller-skating Cher twirling her leg open in an impossible, spread eagle windmill. There’s a kind of crazed, vehement happiness to images of the 70’s and 80’s that seems absurd to me. It’s like the “Mad Men” of the whole two decades needed to convince us that we’d all reach orgasm from buying useless crap and name brands. I’m a bit of a grump about it, but I can’t help wanting to paint it. I’ve told my students for years that your paintings either reflect you perfectly in persona or the complete opposite- one or the other and never in between. I’m definitely crotchety and critical with a great big toothy smile.

Kick, watercolor on paper, 30” x 22”

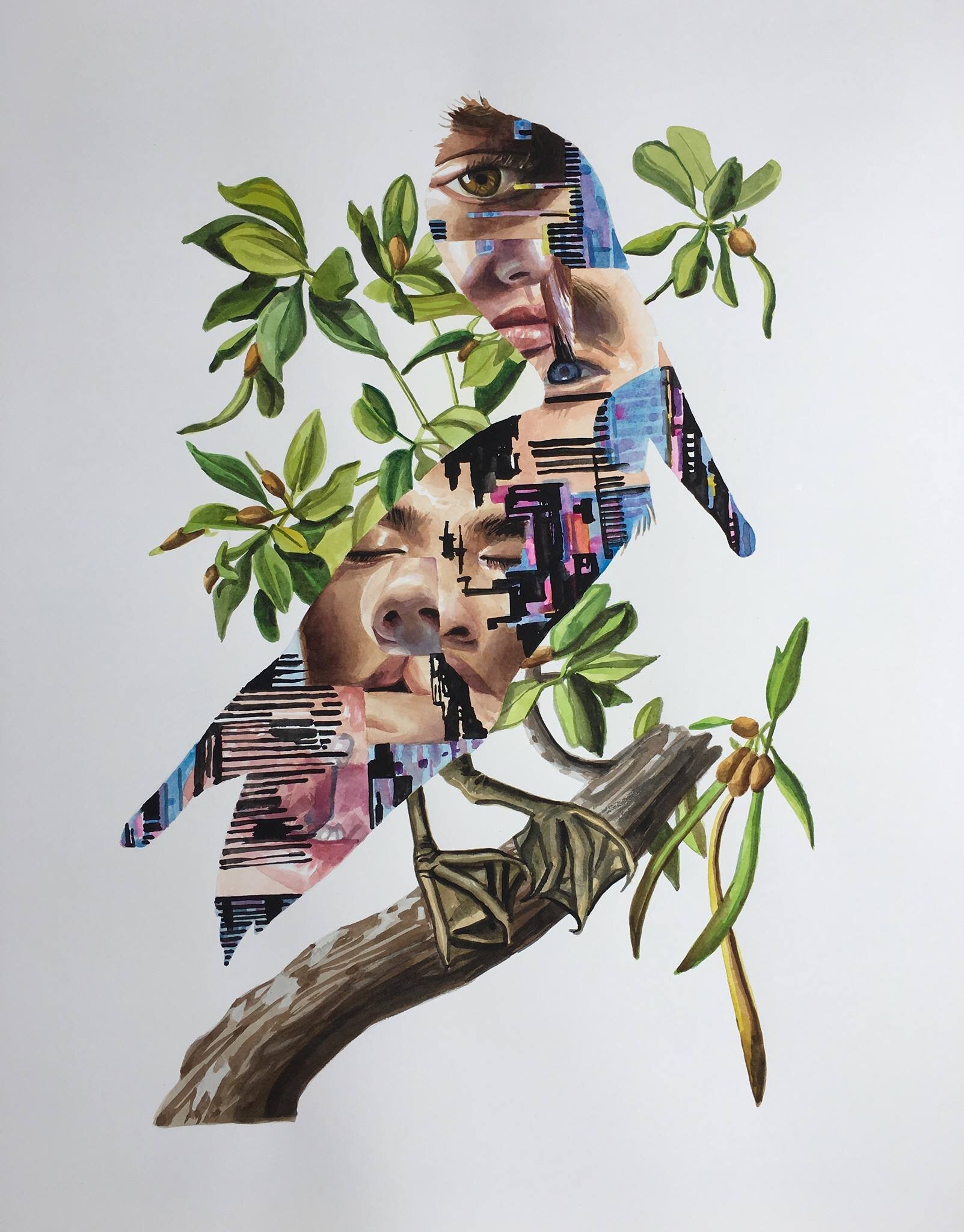

Woodpeckers, watercolor on paper, 30” x 22”

AAS: A few years ago, you started a wonderful series in watercolor called UnNatural Histories. Two of my favorites are Woodpeckers and The Seeing Wreath. They are so captivating and a little spooky. What inspired that series?

MW: I made that body of work for two reasons, because I wanted to paint sensual things and to honor the tradition of watercolor in naturalist illustration. I think a lot about cabinets of curiosity in that wonder can be stoked by objects. Imagine standing around a cabinet at night with your kids and pulling out fossils, shells and prints depicting far off exotic birds. Asking the question, “if a curio had watercolors in it today, what would that look like?” I’m aiming for exotically strange and pure delight. I can’t help but be influenced by advertising and bling, seduction and the visceral quality of surfaces. How in the world do you get a disco ball and pair it with dripping suckers in a painting? So, I essentially remixed these objects within the silhouettes of already existing natural history prints, much like windows. I was looking at a LOT of John James Audubon and Jacques Barraband illustrations. So, I painted the backgrounds pretty faithfully from their sources and redesigned the creatures as a surrealist hodgepodge. I pull tons from Pinterest to create the plans for the paintings.

Seeing Wreath, watercolor on paper, 30” x 40”

AAS: I watched your TEDx video on being an artist and having a more creative life. Very inspiring and insightful. In it you say, “Creating something is intrinsically uncomfortable”. How have you overcome that feeling of vulnerability?

MW: TEDx came to ASU, organized, funded and sanctioned by TED talks. I applied with my talk, thinking it wasn't very esoteric and somewhat inspirational...and it was approved. They don't let you have notes so it's quite nerve wracking in that each talk must be under 17 minutes.

You know, there aren’t many people that make things in our world. We put it off to machines now…for ease and mass production. Making something, ANYTHING tangible-requires the risk of failure. Your soup is lumpy. Your table is wonky. You blew that crocheted blanket for your nephew royally. We see great works in the world created by human hands, and we only see perfection, wherein if one looks closely, you actually do note the imperfections. God doesn’t create in straight lines and so why do we hold ourselves to impossible standards? There is nothing more human than failure. I’ve been able to accept this because I don’t actually believe I’ll ever make a perfect painting. I just try to make the next one better than the last. Keeping going and staying motivated comes from seeing the things you did right as encouragement to continue and seeing the things you did wrong as a lesson. I did a few things wrong in that talk and one thing that I probably should have said was that making is LEARNING and learning is intrinsically uncomfortable. Will you look at that? I made a mistake, acknowledged it and learned. HA HA!

AAS: You recently served as juror of the 2021 Student Competitive at UALR. That must have been a lot of fun.

MW: It’s always an honor to be asked to jury exhibitions and I’ve done many over the years. It’s fun and challenging because the discretion it affords is the thing you have to keep in check. You don’t want to juror a show that COMPLETELY aligns with your own rigid tastes. It reflects a kind of bias and doesn’t honor the diversity inherent in the selections and it certainly doesn’t create an engaging exhibition. So, I pull from experience teaching in that I curate work in that is up to a solid standard and communicates a clear vision from the artist. It doesn’t necessarily have to be beautiful, but it has to be interesting. Juroring, along with many things in the visual arts is horrendous during Covid. I looked at the work digitally and I’ll just say that I’m so over the pandemic. Art, for me is meant to be enjoyed in person. It’s antithetical to expect a facsimile of an experience to honor the artist’s efforts. And for that particular show, the student’s efforts were great. Also, shout out to the curator who invited me, Brad Cushman. He is a gift to the world.

“Art, for me is meant to be enjoyed in person….The fact that an entire generation of artists are now being convinced that one doesn’t need to make pilgrimages to see art saddens me to no end.”

AAS: What are art students most worried about these days and has that changed during COVID since most viewing of art has had to move to online?

MW: Well, I think those are two different concerns for them. In the Delta where I have taught for so long, I think students are most worried about feeding themselves. They are mostly lower middle class and often the first in their families to graduate. They definitely don’t have trust funds waiting for them. Will they be able to make ends meet and be able to make art? I have always related to this because I grew up the same way most of them have, without a safety net and pretty darned poor. The affordance of time is the biggest constraint in that one needs a good deal of it to make anything worthwhile. Time is the actual currency of the privileged class. They want to be able to be creative in their occupation, honor their gifts and make ends meet. So many of them have to give up on this once they go out there and see the hand they were dealt. A career in art takes a long time to build.

As far as COVID goes, I’ve noticed that young artists feel more isolated and left out. For young people the internet is the place they go for affirmation, confidence and permission to do bold things. They don’t look to the things we probably looked at as kids as much. Instagram is their beacon of creative inspiration, but it’s also riddled with minefields and untruths. “Likes” don’t actually sell artwork, the hustle does. They seem obsessed with what I call “varnishing porn.” You know those videos of folks making really mediocre paintings shiny with too much glossy varnish. Smoking hot young artists taking lots of selfies in front of their work but not actually making any. So many selfies! It’s also a platform that only reflects the successes of artists in their studios and never the absolute turds that we avoid showing people. The world thinks the work comes so easily, without failure and without trail. So, to be frank, the iterations of art online reflect only the candy of the art world. It tastes sweet but has no real nourishment. The fact that an entire generation of artists are now being convinced that one doesn’t need to make pilgrimages to see art saddens me to no end. And if they finally get there, they look at it through their phone wondering if it’ll be good “Insta” curation. Life isn’t meant to be entirely lived behind a screen.

AAS: What is next for you, Melissa?

MW: I’m going to try a make a living just selling my paintings in the New York area, where I moved a week ago. Wish me luck because I’m absolutely terrified.

AAS: I certainly wish you all the best success!