Interview with artist Marjorie Williams-Smith

Marjorie Williams-Smith has worked with silverpoint for over 30 years. This drawing technique delivers the beauty, serenity and mystery her work is known for. Following a career as a graphic designer, she took up this art form only after moving to Little Rock in 1982 with her husband Aj, also a renowned artist. Marjorie has had a distinguished career teaching art at UALR for over 30 years and is in demand as a lecturer, author and metalpoint workshop instructor. Her works can be found at her website, Hearne Fine Art in Little Rock, and the Arkansas Arts Center.

AAS: You earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts from Howard University, Washington, D.C., then a Master of Fine Arts from Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York. Did you grow up in the northeast?

MWS: I was born in Washington, D.C. and lived there until I moved to New York for graduate school. Most of my relatives lived in Maryland and Pennsylvania. So, my early years were pretty well grounded in the mid-Atlantic region.

AAS: You came to Little Rock and the University of Arkansas at Little Rock as an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Art in 1980s. What prompted that move to the south?

MWS: I met my husband, Aj Smith, at the Robert Blackburn Printmaking Workshop in New York City. He was working there as a master printmaker. We married and lived in Queens, New York. In 1982 Aj was invited to interview for the Artist-in-Residence position at the Arkansas Arts Center. When he told me about the interview, I was not excited. I thought if he was awarded the position, we would have to move to Arkansas but I did not want to do that – at all! When I thought of Little Rock, Arkansas, I could only remember the 1957 Central High School crisis. Well, the interview was successful and Townsend Wolfe, Director of the Arts Center, offered Aj the position. Now, Aj had to convince me to move. It just so happened that I was extremely busy at my job. I worked as a graphic artist for a marketing company. The art department was working on a big promotional campaign that needed to be done ASAP. I was tired and we had just learned that I was expecting our first child. Aj suggested that moving to Arkansas would give me a break and I could focus on having our baby. Also, he said we could move back to New York after a year, if we didn’t like Little Rock. What can I say? We stayed! Aj accepted a position at UALR and a year or so later I excepted a position as well.

“When I draw with metals, there is a whole different feel to it than when I draw with graphite pencil. I sense a smoothness as I leave a mark on the page.”

AAS: In 2017 you retired from UALR with emeritus status after 33 years. I recently retired from UAMS after 29 years of research and teaching. What I miss most is the interactions with students. What do you miss most after retiring from UALR?

MWS: I really enjoyed seeing the “light bulb moment” for a student when they grasped a new technique or made a discovery in their art work. I could see the student gain confidence and take on a willingness to push themselves further. That was really rewarding.

AAS: You have clearly kept busy since your retirement from teaching – conducting workshops and exhibiting your new works. You are regarded as an authority on silverpoint and a master of this drawing technique. Recently, [February, 27, 2020] you delivered an invited lecture at Hendrix College entitled “The Resurgence of Silverpoint: A Contemporary Approach”. Talk about silverpoint and its history.

“Writing or drawing with metals has a long history dating back before the Renaissance.”

MWS: Basically, silverpoint involves drawing with a silver tool on a drawing surface prepared with a coating. The terms silverpoint and metalpoint are often used interchangeably. Silverpoint makes use of silver. Metalpoint refers to drawing with any metal other than silver, such as copper, gold, aluminum, or brass. Metals will not leave a mark on plain paper, but it will leave a mark on a surface coated with a ground. For a ground you may use acrylic gesso, a traditional ground (crushed marble, rabbit skin glue, and pigment), gouache, or watercolor. You may also use commercially prepared paper.

Writing or drawing with metals has a long history dating back before the Renaissance. Vellum, parchment, or wood panels were used as the drawing surface until the introduction of paper to Europe in the 12th century. Drawing preparation took a great deal of time and work because artists had to make their own ground. Reference materials suggest that artists mixed ground chicken bones with animal-skin glue, a pigment for color, and saliva or oil. This ground was applied to the drawing surface and allowed to dry. If an error was made in the drawing process, the mark was removed with dried bread crumbs. Removing the mark also removed the ground, so errors were avoided as much as possible. Drawing with metals reached a high point in the Renaissance. Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and Filippino Lippi were among the many artists who made drawings with metals.

AAS: What encouraged your interest in silverpoint?

MWS: I was introduced to silverpoint drawing when I saw the exhibition The Fine Line: Drawing with Silver in America at the Arkansas Arts Center in the fall of 1985. This exhibition was organized by the Norton Gallery and School of Art in Florida. The work was amazing! I visited the exhibit many times to view the work up-close. How were these drawings made? I purchased the catalog and read every detail. The catalog included an essay by Bruce Weber who was Curator of Collections at the Norton Gallery of Art. This essay provided information on the tools some of the artists used in their drawings. I was determined to give it a try. My first silverpoint tool was fashioned from a silver ring. I tried using silverpoint as if it were a pencil – using a continuous tone to build value. The result was not what I expected. I studied the catalog further and found that many drawings were constructed with hatched and cross-hatched lines. Realizing this, I worked on this technique to gain more control with the silverpoint tool.

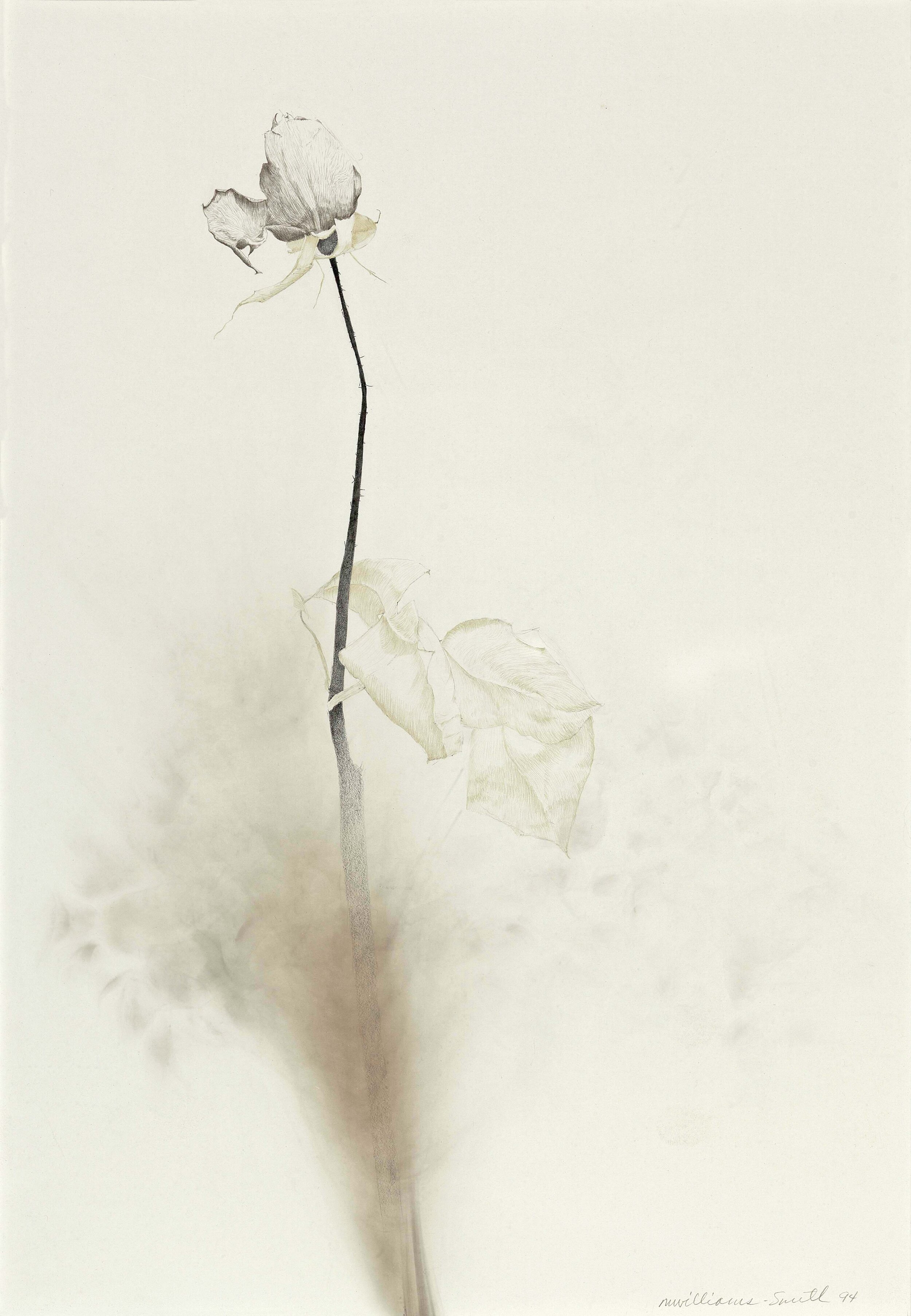

AAS: What does metalpoint offer to you that other media or techniques may not?

MWS: When I draw with metals, there is a whole different feel to it than when I draw with graphite pencil. I sense a smoothness as I leave a mark on the page. Maybe this is because I am drawing on a smooth ground rather than the texture of paper. I am also enamored with the precision of the line. My tools are sharpened to a slightly rounded point. The drawn line is thin in width. Adding pressure to the tool will not increase the line width. In fact, if too much pressure is applied, the tool may scratch the ground. Working slowly allows me to focus on what I am doing and think two or three steps ahead so I can avoid errors. The other quality I like about silverpoint is that the silver tarnishes. The initial silver mark appears as a cool gray. But over time the tarnished silver takes on a warm brown tonality that will also become darker in value.

“Drawing with metals reached a high point in the Renaissance. Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and Filippino Lippi were among the many artists who made drawings with metals.”

AAS: You frequently use a combination of metals in a single work – aluminum, gold, copper as well as silver. What special quality does each metal bring to the piece?

MWS: After working with silver, I wanted to try some of the other metals that were used by artists in the Fine Line exhibition. My research informed me that copper would tarnish and become greenish. I tried it in hopes that my mark would turn green. After a year I was surprised to find that it had turned yellow! From this I learned that environment and air quality can impact the tarnishing of the metal. Later, I purchased a small piece of gold wire and tried it. Gold does not appear gold on the page. It is gray, and because it does not tarnish, it remains gray even as the drawing ages. After I learned how the metals aged over time, I started using them together. The differences were subtle which added an alluring quality to the drawings.

AAS: What types of artists are participating in your workshops? Are you hoping to inspire new artists to help ensure this art form continues in Arkansas?

MWS: The participants in the silverpoint workshops vary in age and skill level. It really depends on the venue in which the workshop is offered. Workshops at colleges and universities include students who have had academic training in art. Workshops at art centers or in a gallery setting attract a more mature art enthusiast. The skill level here may vary but I encourage everyone to enjoy the process. Whether the participant is a novice to art, an art student, or someone who has created art for a while, I hope everyone can gain an appreciation for the medium. There have been a number of participants who have said they will continue to work with the medium. This makes me happy.

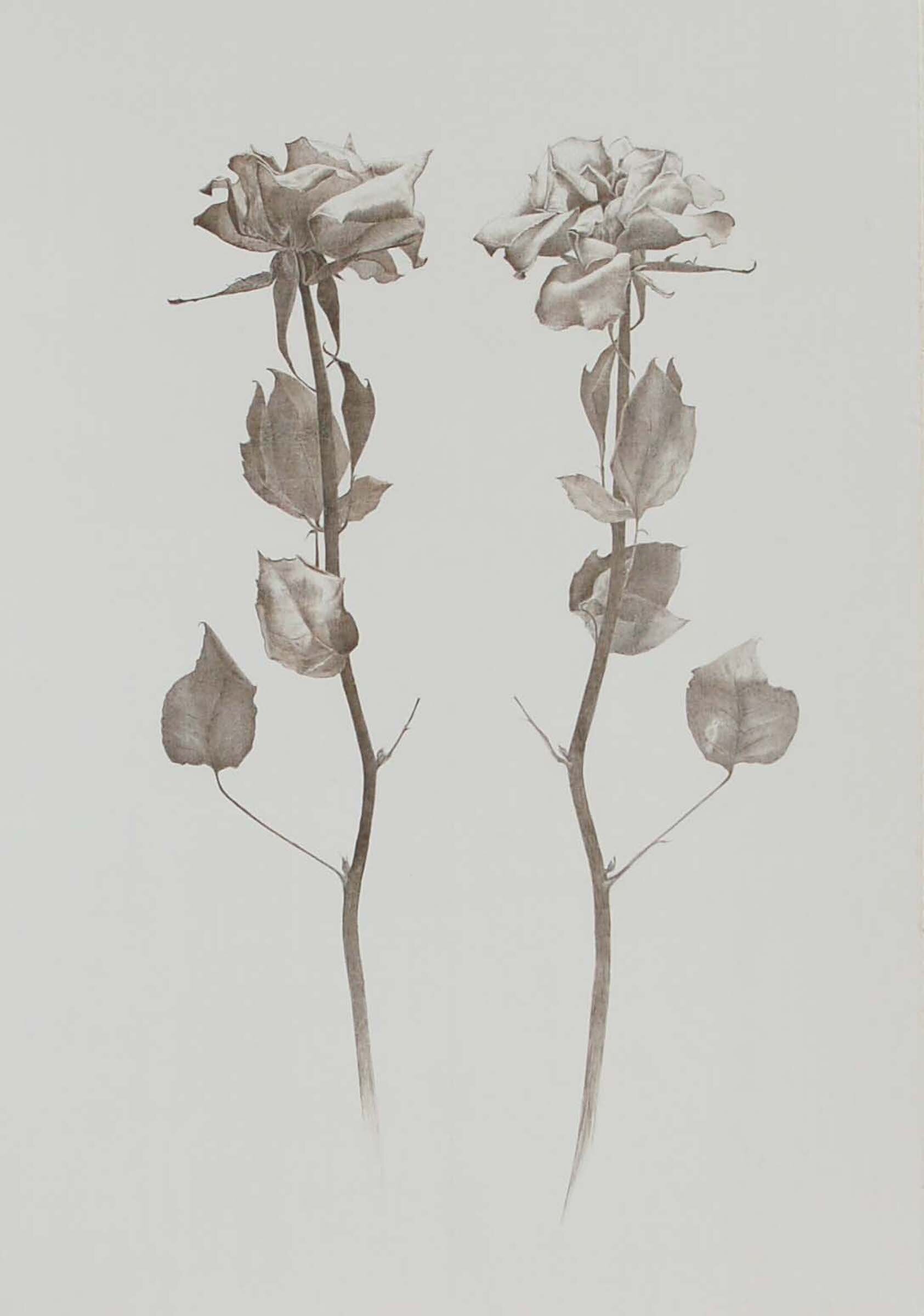

AAS: Your floral still lifes are in many ways spiritual. I especially love Life Cycle: What Remains. For me it is a very moving piece. What is it about the beauty – and the fragility – of flowers that inspires you to want to capture them in monochrome?

Life Cycle: What Remains, silverpoint, copperpoint and graphite on gesso-coated paper, 30” x 20”

MWS: I have always loved flowers. I think I got this from my Mom. Although we had a small backyard, she was able to plant a variety of flowers with colorful blooms. Often, we would cut small bouquets, put them in vases and place them around the house. I missed this when I moved to New York. So, I would buy fresh cut flowers at the market to brighten my apartment. For my first Mother’s Day, Aj gave me a bouquet of roses. Instead of pressing them in a book, I let them sit on my drawing table. Even as they aged, they were fun to observe. The petals went from bright red to a deep crimson. The leaves twisted and curled and the stems became very hard and dark in value. After they were fully dried a few of the petals fell off. One day while our daughter was napping, I decided to draw one of the roses in pencil. This felt very relaxing. That led to many more rose drawings. I loved the fragility of the petals and leaves, but I was well aware of the hard, sharp thorns. Those drawings represented how something or someone may appear fragile but there is a strength present that must be respected. Over time my drawings included other types of flowers. Because I work slowly over a long period of time, the process is like meditation and prayer. When I was teaching and raising two children, my days were quite hectic. But when I stepped into the studio, I had to calm down. Classical music helped. It also helped to have Bible verses and quotes of encouragement written on small post-it notes taped to my drawing board. Drawing became a way to get in touch with my spiritual center. Life Cycle: What Remains is a good example of this. This dried coneflower was in my backyard. I thought about its beauty when it was in full bloom. But to me it was still beautiful because it told the story of life. Death is part of the life cycle, but what remains is the spirit and there is strength in that.

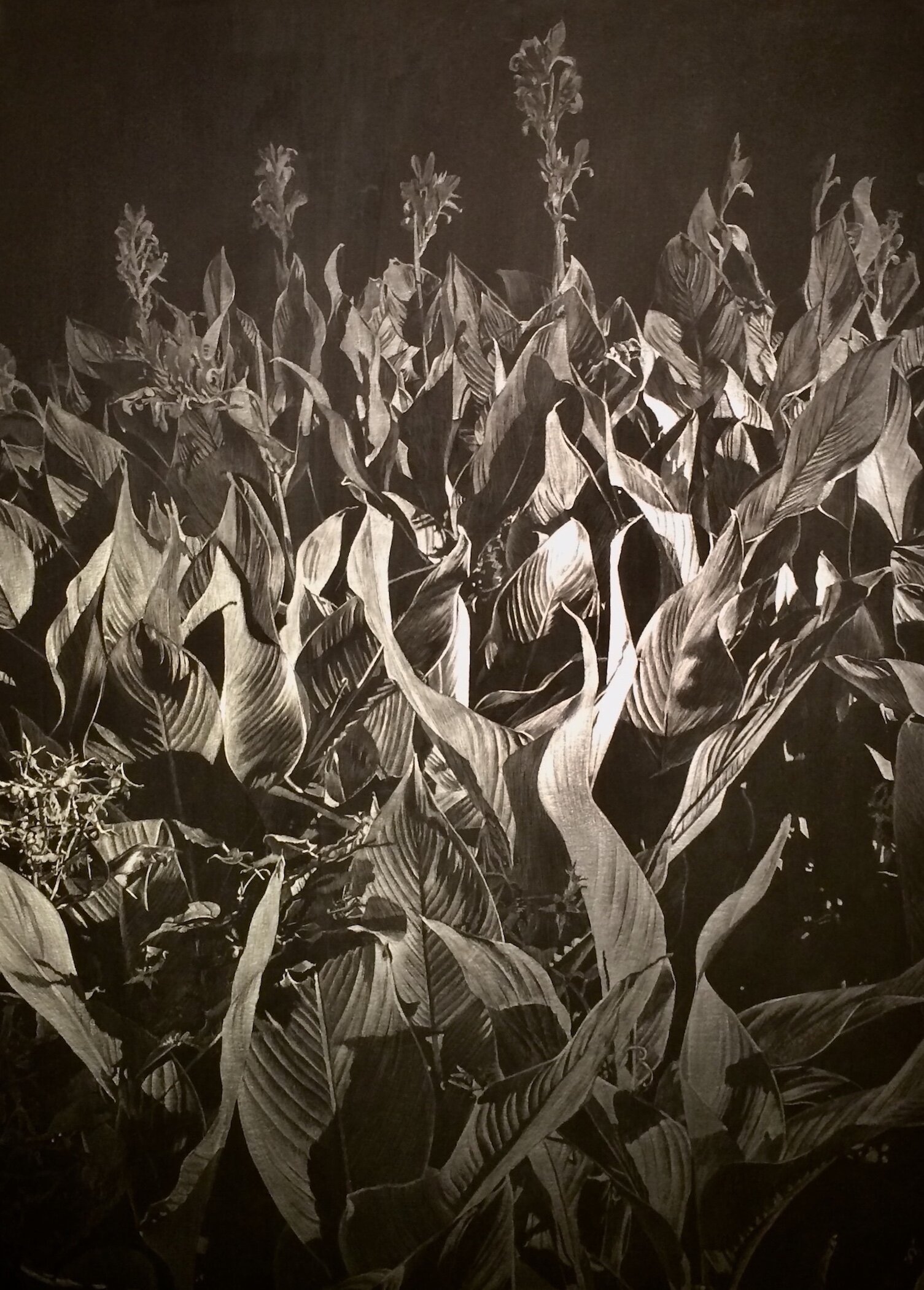

Strong, aluminumpoint, copperpoint on black acrylic gesso-coated paper, 5 3/16” x 3 1/2”

AAS: I really love how your dark background pieces have so much mystery. They ‘force’ the viewer to get up there face-to-face with the piece. In a way, it is almost an intimate viewing.

MWS: My friend Susan Schwalb suggested I try drawing on black gesso. Susan is an internationally recognized master in silverpoint. I have loved her drawings since I saw them in the Fine Line exhibition. After making one or two drawings on this color ground I realized I had to change my thinking and drawing approach. It was like drawing in reverse. Instead of using the metal to draw the mid values and shadows, I had to use the metal to draw the light. Once I figured this out, I was really hooked. On black, the metals appear as the local color of the metal itself: gold appears yellow-gold, copper appears red, aluminum appears white, and silver - once it tarnishes - appears brownish. I agree with you that the dark ground adds a layer of mystery or magic to the drawing. For example, in the drawing Strong, black acrylic gesso was used as the ground. The coneflower was drawn lightly in pencil. Lines radiating from the cone were drawn with aluminumpoint. Copperpoint was used to describe the petals and the spikes of the cone. I think the spikes on the cone head are powerful but the aluminum rays give it a sense of grace. I encourage viewers to step in closer to my work to really see all that is in the image.

“After I learned how the metals aged over time, I started using them together. The differences were subtle which added an alluring quality to the drawings.”

AAS: Talk about your involvement with the Arkansas Committee of the National Museum of Women in the Arts (ACNMWA).

MWS: I am a new member of ACNMWA having joined the organization in January of 2020. This organization is an affiliate of the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C. and supports and promotes the creative work of Arkansas women artists and arts professionals. I joined this organization to help spread the word to more women artists about the opportunities ACNMWA provides. Advocacy for Arkansas women artists is accomplished through four ongoing programs: the Artist Award to support new creative work; the College Internship Stipend to encourage educational excellence in the arts; guest-curated art exhibitions; and through its affiliation with the national museum’s biennial competitive Women to Watch. I’m sure there are many women artists in our state that do not know of these opportunities. I hope my participation will help increase awareness and support for ACNMWA’s activities.

The Congressional Medal of Honor (front side), awarded to the “Little Rock Nine” in 1998

AAS: You have earned so many prestigious award and honors – I will not ask you to say which you are most proud of, but I would like for you to talk about designing the Congressional Medal of Honor awarded to the Little Rock Nine by President Bill Clinton in 1999. That must have been an unforgettable experience.

MWS: It seems ironic that someone who did not want to move to Arkansas because of the Central High Crisis, winds up creating the design for the Congressional Medal of Honor awarded to the Little Rock Nine. In 1982 I had no idea I would one day have a part in the history of the Little Rock Nine. Everything in this life happens for a reason! I was contacted by Joey Halinski, a UALR graduate, about submitting sketches for the medal project. Although she had moved out of state, she learned that the U.S. Mint was looking for an artist to work on a design for the medal. She gave me the contact information for the Mint and I soon contacted the project coordinator. Immediately I started to think of ways to design the medal. All of my ideas included illustrations of the nine students. However, once I got the full details from the project coordinator on what was required for the medal, I learned that I could not use any pre-existing photographs to create my design. I had to scrap all of my ideas! How could I portray the students’ heroic moment of entering Central High School without using any photographs from those events? So, I thought about it. You don’t necessarily have to see the students faces. What if I portray the students walking up the stairs to Central High and you see the students from behind? So, my husband and I went to Central and took photographs of the building, the school entrance, and the front stairs. I also asked Aj to walk up the stairs and pose in several locations. He also posed holding a broom stick as if he were a soldier with a rifle. Next I asked my oldest daughter to pose with a poodle skirt (which she just happened to have) and walk up the stairs (in our backyard) carrying a notebook and books. From these many photos I was able to develop my illustration of the nine students ascending the front stairs of Central High School. This illustration was used for the front of the Congressional Medal of Honor. When I saw the medal on display at the Clinton Library, I was very proud!

“It seems ironic that someone who did not want to move to Arkansas because of the Central High Crisis, winds up creating the design for the Congressional Medal of Honor awarded to the Little Rock Nine.”

AAS: Just last year you received the Governor’s Art Award for Individual Artist. That is high recognition and must make you proud to know you have made a real impact on the arts in Arkansas.

MWS: It was truly an honor to receive the Governor’s Art Award. I have had the opportunity to meet so many people in Arkansas because of the arts and this has been a true blessing. I remember one afternoon, Aj and I were visiting the Arkansas Arts Center, viewing an exhibition of work from the permanent collection. One of my drawings was on display along with a photograph of me. It just so happened that a group of African American children was touring the gallery with their teacher. They were from a small school district in Arkansas and this was their first visit to the Arts Center. We could tell that they were very excited to be there. As I was looking at a few images, Aj stepped away to talk to some of the students who were looking at my photograph. He asked them if they would like to meet the artist. They looked over, saw me and were quite surprised. They were so excited to meet a real artist in person. I gave them an impromptu talk about being an artist. Their questions were so sincere and I could see how much it meant to them to meet a real artist – who was also African American. Like I said earlier, everything happens for a reason.

AAS: You mentioned your children. Having grown up in a very artistic household, have any of them pursued a career in art?

MWS: Our daughters, Nilah and Aeisha, are very artistic. Growing up they had access to most of our art supplies and they made great use of this. All of their school art projects were stellar (in my mind). As adults they have not chosen art careers, but they are both very creative. I’m really happy that they visit art museums on their own, without parental prodding.

AAS: You and your husband Aj Smith are Arkansas art treasures and have been collected by museums and private collectors throughout the US as well as the home collector who can afford only a few special pieces. That must give you both great satisfaction.

MWS: The objective and reason for being an artist and continuing to make art, even after retirement, is that the artwork is a way to communicate with others. Whether it is a corporation, museum, or an individual, we try to establish a relationship with other people. We are not trying to tell others something they do not know, but rather, speak to all that we share – our spiritual, emotional, and physical connectivity. Hopefully, viewers will connect to something they have seen in our artwork. That is really rewarding.