Interview with artist Kim Brewer

Kim Brewer is an artist living and working in Little Rock, Arkansas. Her work explores social justice issues with the intent to raise awareness and promote discussion. This passion developed during her time at Texas Woman’s University where she earned a BGS in Women’s Studies and Criminal Justice then an MFA in Drawing & Painting. Kim has exhibited her work throughout Texas and now Arkansas and is currently in the traveling exhibition Arkansas Women to Watch 2021: Paper Routes. More of Kim’s work can be found at her website kimbrewerart.com.

AAS: Kim, you attended college in Texas. Are you originally from Texas? If so, how did you end up in Little Rock?

KB: During my last semester, my wife was offered an amazing job opportunity here. It was too good to pass up, so I spent the last semester of graduate school commuting back and forth from Little Rock and then I moved here once I graduated.

AAS: You describe your work as an investigation of social justice issues. Has this always been a topic you’ve wanted to explore with your art?

KB: Yes, social justice has always been a topic of my work although not always as directly as it is in my current work. Just existing as a young lesbian in in the 90s in Texas was a political act. When a large part of the world is opposed to who you are as a person, most everything is political from goods and services to the big stuff like strangers trying to talk to me about the eternal damnation of my soul. In college, I vacillated between art, criminal justice, and women’s studies. In the end I got my BS in general studies and then went into post-baccalaureate classes in women’s studies because I still felt like I needed solutions to all of the political issues I had been wrestling with: poverty, inequity both gender and race-based. I didn’t know where I fit in any of the conversation, but I was definitely forced to wrestle with my privilege in society. I went back to the art department and committed to an MFA because art is, and always has been, how I see and experience the world. It has been the thing in the hopeless heaviness of this world of social injustice that has made me know change is possible. I think people are more susceptible to considering ideas that in other formats might be entirely unapproachable, but art creeps in through the senses and it changes people, sometimes in spite of their own politics.

“I think people are more susceptible to considering ideas that in other formats might be entirely unapproachable, but art creeps in through the senses and it changes people.”

AAS: Your portrait images are vibrant, often stark. I find this adds to the aggressive feel of the image. And I believe you’ve said they are inspired by mugshots, which are meant to be emotionless, but of course never are?

KB: I ran across a mugshot newspaper in a local gas station when I was an undergraduate and I couldn’t escape the haunting nature of the images as portraits of state control. I also started reading Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida around the same time. Barthes explored the nature of photography and the relationships and dynamics of power between the taker of the image, the sitter, and the viewer. I then felt an odd sense of responsibility to try to reinterpret these images from another perspective. If the mugshot is an involuntary image of state control, I wanted these images to be viewed from the perspective of one who seeks to understand. As a society, we are responsible for each other in both big ways and small. I think it is more evident than ever now that we have all walked through a pandemic together some masked, others not. We are killing each other with a virus now, but it’s been happening slowly daily through social apathy for decades it’s just been made undeniable this past year. When we talk about criminal justice reform, we talk about recidivism, race in America, and education. The problem with the whole thing is the chronic disenfranchisement of those who are the system’s harshest critics. How can the system be changed if those who it has failed are not allowed to vote to enact change? These are the issues and questions that I was wrestling with when I engaged in this type of artmaking. I wasn’t sure where it would go but I knew it would open a lot of doors to have conversations about things that need to change in this country.

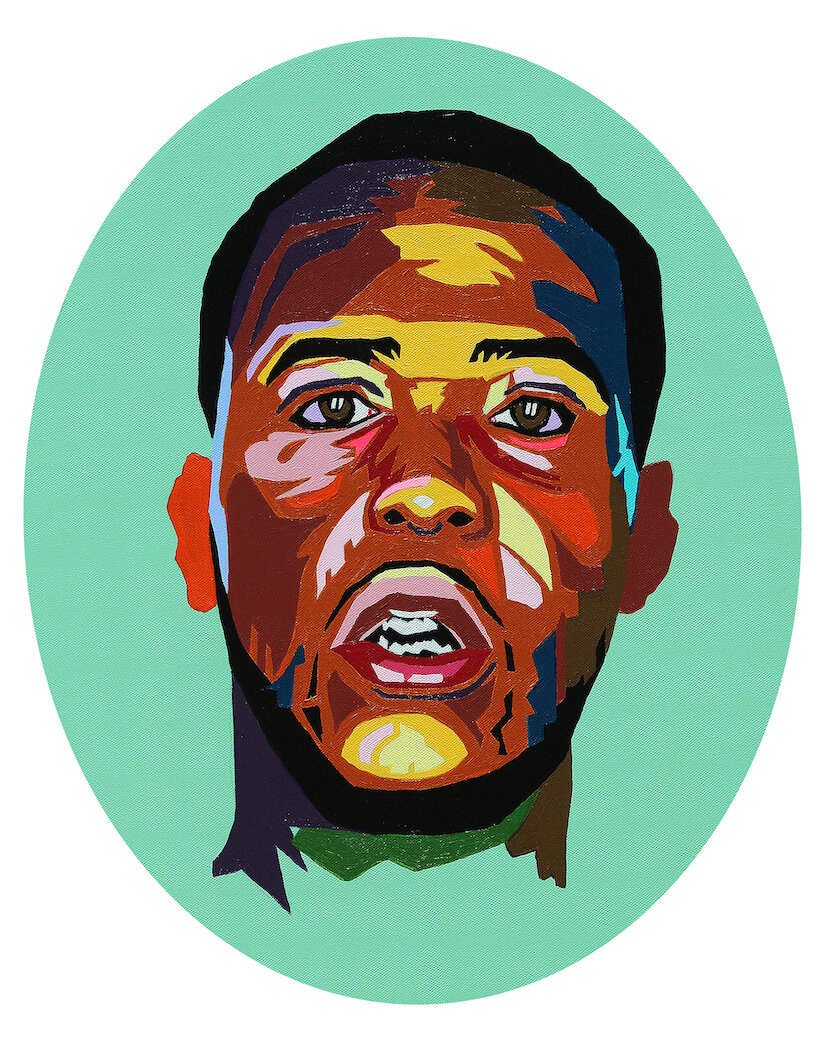

AAS: Would you comment on your “Alleged Shapes” series? Alleged Shapes No. 5 is an especially haunting image with its wonderful use of color as shading.

Alleged Shapes No. 5, acrylic on canvas, 20” x 16”

KB: When I began working with mugshots as source imagery, it was important to me to interrupt the image, but my artistic background was almost exclusively in photorealism. The work started to evolve through using craft mediums to interpret the images in a more domestic context. Stepping off from that experience, I began working on the Alleged Shapes series by collaging construction paper. My thinking with this series was referencing specifically the abstract and intangible nature of the mugshot in our current society. Mugshots were originally intended to exist as physical images in limited possession for the sake of identification. The modern mugshot is wielded as a weapon of perpetual incarceration for offenses that may or may not be the fault of the person in the image. In abstracting the images, they are broken and reassembled. The process of creation begins, as these images did, in a very physical place with cut papers and moves to a digital editing process, and then to painting. The play between mediums in both their creation and in the resultant image creates a tension and an autonomy that satisfies my need to give the images their own life and identity separate from the original. This series references Victorian cameos in its composition and orientation in a desire to lend to the pieces a kind of familial preciousness found in those objects.

AAS: You were chosen as one of the Arkansas Women to Watch in 2021 and are exhibiting in the Paper Routes State Tour, curated by Allison Glenn of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. This must be very exciting to know your unique style of portraiture was not only recognized but will be viewed all around the state.

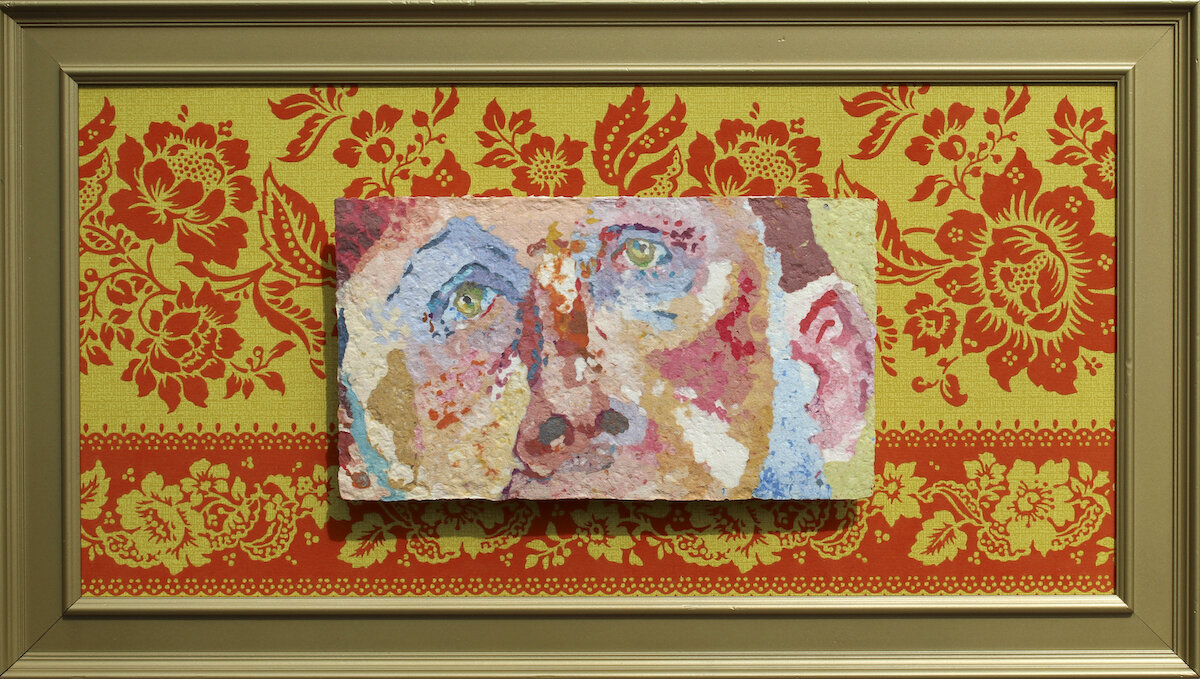

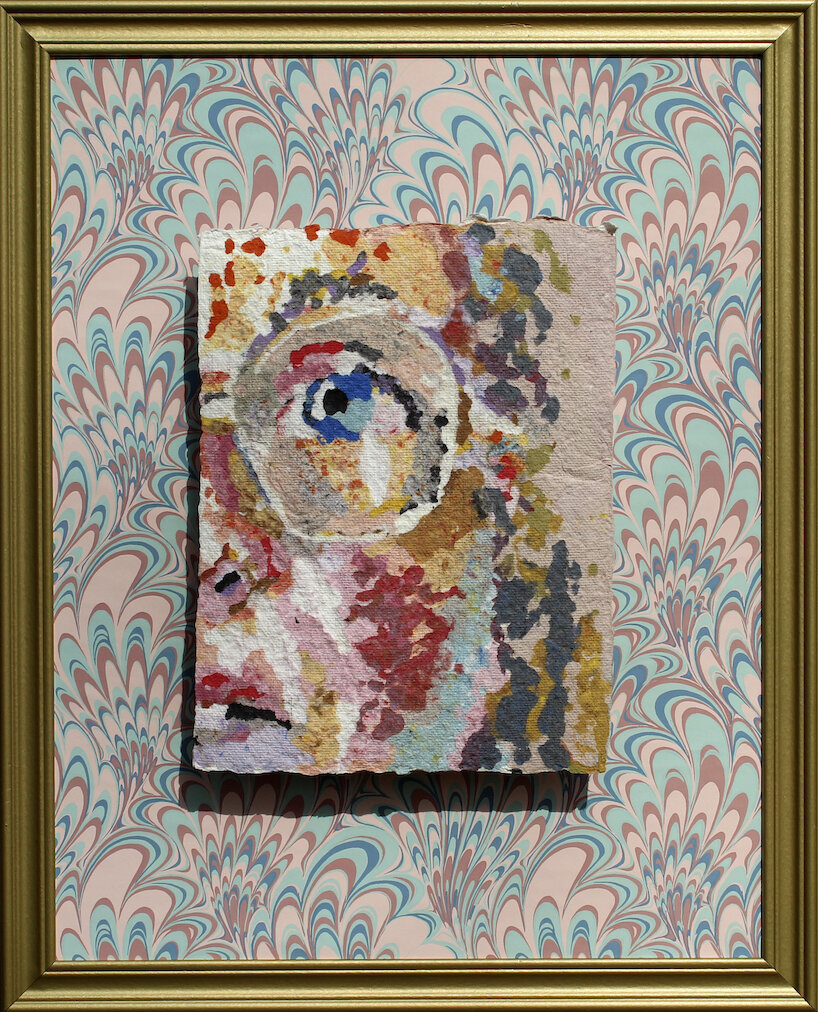

Rosebud Moments in Paper Planes No. 3, pigmented cotton linter pulp, vintage wallpaper mat, found frame, gold spray paint, 28.5” x 24.5”

KB: Yes, being chosen has been exciting. Making work that is personal and political isn’t always the work that appeals to people. I have always wanted to make work that that didn’t require a degree to appreciate. When the work can also be recognized by someone as highly respected in the art world as Allison Glenn, it is a real honor. Contemporary portraiture can take so many forms and these pieces definitely live on the edge of that genre.

Rosebud Moments in Paper Planes is a series of handmade pulp paintings which have been hung on vintage wall papers placed in found frames that have been spray painted with a faux gold finish. The pulp paintings for this series were done from sketches I had made of several mugshots. I was in a paper making class as part of my intermedia minor in grad school and I decided to work on a cropped portion of the image. Pulp painting as a medium does not lend itself to detail so I wanted to highlight the best aspects of the medium. You have to work blindly onto the surface of the mould as the water drips through, so not only is there an unknown element to the process, there is also an immediacy to it because you cannot let the work dry out. The pressure and tension in the mediums and its strengths and limitations really opened up a world of conceptual approaches to working with the images.

The addition of the wallpapers situated the pieces in a domestic space so that they may be viewed as portraits of loved ones or family members rather than objects of documentation. The series title Rosebud Moments in Paper Planes references the film Citizen Kane and the idea that each of us has moments in life that if other people knew about, we would instantly make sense to one another. These pieces are in a lot of ways about giving the viewer an opportunity for empathy. No one knows what another person is alleged to have done or their experiences and possible choices in a given moment.

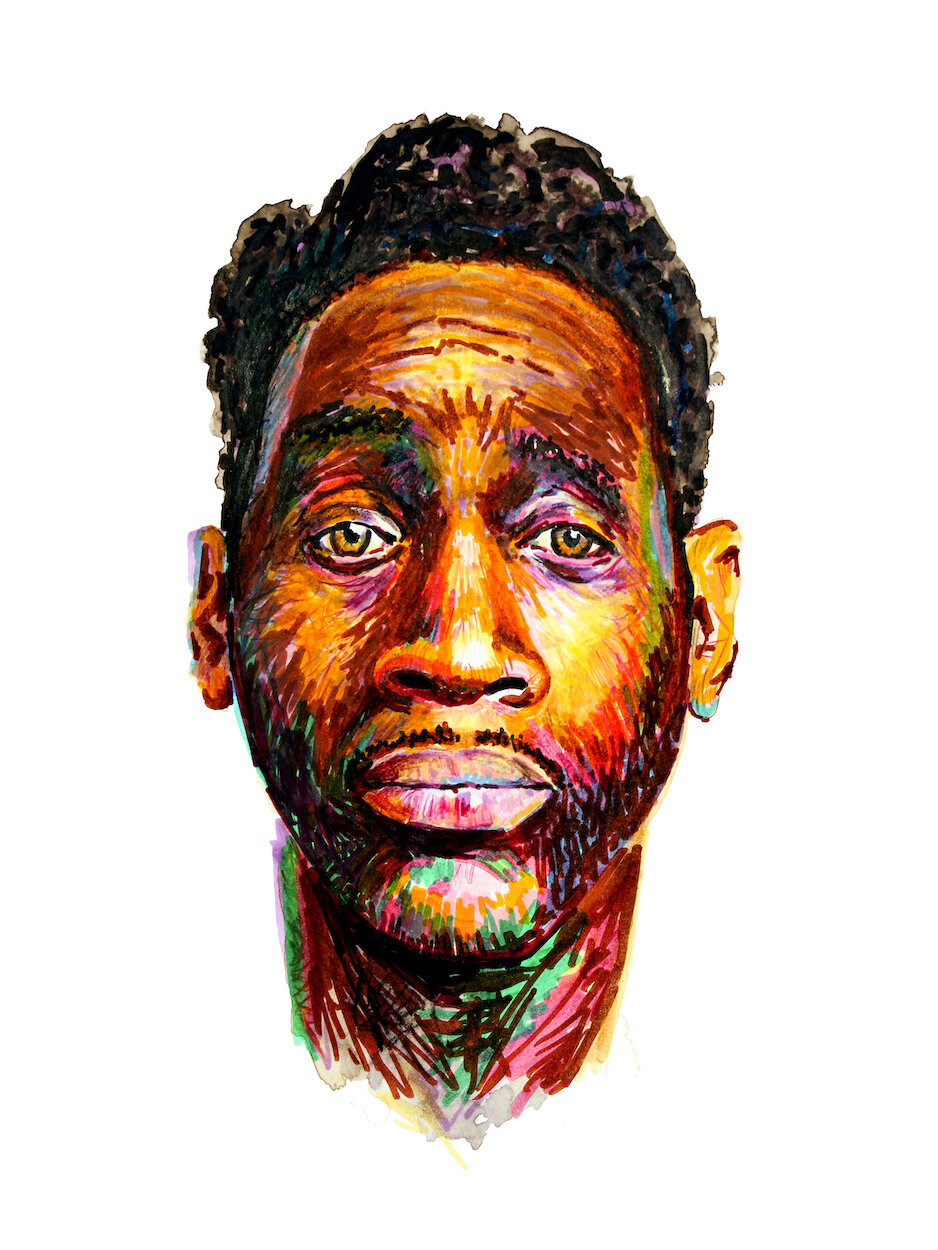

AAS: You’ve done another series called the “Marked” series. These almost have a courtroom sketch feel to them. I love your use of the color marker.

Marked No. 1, marker, watercolor and colored pencil on paper, 12” x 9”

KB: Marked was completed at a time when I was struggling with how to best approach the images to give them the most life, individuality, and emotion as possible. These images were also sourced from mugshots. In some ways it was a transitional series that became a color and value study for the use of other mediums. After my series Rosebud Moments in Paper Planes, I had come to the realization that a lot of the conceptual power of the work was coming in the exploration of the mugshot in different mediums. I became primarily interested in using craft mediums or those that have historically been viewed as the low arts like crewel embroidery. Having the images presented in a variety of ways opened up the conversation around the work to include not only the sociopolitical attitudes around the prison industrial complex but also to look at what we consider painting in contemporary art and a lot of the perceptions that still linger around the primarily male dominated medium. Many of these mediums were also slow to produce and were difficult to work in expressively. I was looking for a process to add to the way in which I had been approaching each medium that would allow me to be free and spontaneous in the visual language of the piece. I used a cropped portion of one of the Marked pieces as a reference to make a latch-hook rug for my graduate show. Having that extra step of removal from the original image lends to it a further sense of abstraction which really worked well in trying to interrupt the intended purpose of these images.

AAS: But you have done more than just portraits that comment on societal extremes, at least some would call it extremes. American Veritas is an extraordinary work. I find it unsettling and all too relevant to the current craziness of American society, especially these days. The glass of milk and placemat, for me, really make it an alarming image. Brilliant.

American Veritas, acrylic on canvas, 24” x 24”

KB: Thank you so much for your comments. It was my aim to try something a little different after I graduated. I had been working almost exclusively on faces for 5 years or so. I wanted to do my take on a still life. I had just moved to Little Rock where the murder rate was exceptionally high per capita and at the national level mass shootings were becoming a very regular occurrence in the US. I wanted to situate these elements at the dinner table, the place for discussion. In using the TV dinner, I am saying this individual is eating alone, so there is a kind of apathy present here or even the illusion of American individualism/exceptionalism. The visual weight given to the presence of the gun at the table is the same kind of familial importance that too many Americans give to their weapons – the same kind of domestic banality as the glass of milk.

My father was a conservative gun-toting Texan who believed in the primacy of having a loaded gun in the house at all times. I grew up with a large amount of anxiety because of this as a kid. I was made to feel as though I needed to be ready to be attacked at any moment. I realized in adolescence that my dad’s need for a gun to protect him from this “other” was a sad embodiment of his overt xenophobia. This was about the same time that I was coming to the realization that I, as an LGBTQ youth, was an “other” to him.

AAS: FolkAF No. 1 is quite a different piece. “I can make it pretty if that will help” – would you talk about it and its imageries?

FolkAF No. 1, acrylic on canvas, 36” x 36”

KB: Yes, FolkAF is taking my work in a new direction but it is a logical outgrowth from my life-long interests in feminist ideologies and folk arts. It started for me with the phrase “…if that will help.” It originates out of the feeling of expectation placed upon women to be in a place of obliging. I am a wife, a daughter to an aging mother, and new mother to an 11-year-old. I am a kind person by nature, but the expectation that I often feel to maintain that space at all times in those identities is almost metaphysical. In addition, I am speaking to expectations that exist around being an artist wanting to speak about challenging subjects like poverty, gender and economic inequity, race, and the social divide between rural and urban America. Folk art to me has always been a tool of individual autonomy especially for women so that format for these works just made sense. Using a mirrored composition not only references quilt motifs but speaks to the idea of a mirror as a tool for self-reflection.

AAS: Kim, what artists do you admire most or have inspired you the most?

KB: The artists that I feel most artistically impacted by are second wave feminist artists like Judy Chicago, Miriam Schapiro, Barbara Kruger and contemporary artists Nina Chanel Abney, Mickalene Thomas, Ebony G. Patterson, Jeffrey Gibson, Greg Ito and Amir H. Fallah. The contemporary artists that I have mentioned all share a flat graphic approach to modeling in their work which I am highly drawn to. Gibson, Thomas, and Patterson all also have historically incorporated other mediums (often craft mediums) into their painting processes. To me, these artists reference the art historical dilemma of the relationship between folk/art and art/craft and progressing the idea of what constitutes contemporary painting in America.

“Make the art you want to see and believe in what you make because it will be rejected constantly and the making of it must sustain you.”

AAS: What advice do you have for artists, particularly women artists, who have decided to put themselves out there and try to make it as a full-time artist.

KB: As a full-time artist and more specifically a woman entering this field, I would say first and foremost is know yourself. There are no real new movements, and yes you must know art history, but this contemporary art world is one of combinations and lenses. You are all you’ve seen and experienced and the way in which you see the world and make art, if authentic, will be enough. Make friends who will be honest in their critiques and supportive of successes. Many people want to “make it,” very few also want others to do so. Keep those people close. Try to organize your time in the studio daily. Try to have something going that is a continuation of what you have been working on, but also devote time start something new and exploratory at least once a week. I am stingy with materials so for me that meant gathering seemingly useless inexpensive things and collaging as a means of composing. Find what works for your process. Make the art you want to see and believe in what you make because it will be rejected constantly and the making of it must sustain you.