Interview with artist Jerry Phillips

Jerry Phillips is an artist living and working in Little Rock. He considers himself a collector – a collector of images from which he extracts their essence to create remarkable drawings that transform the image into something quite magical. His skill with graphite is so remarkable that is it easy to forget these are rendered by hand. Jerry’s work is in major collections and museums in the US and in Europe. More of his work can be found at his website and at M2 Gallery in Little Rock.

AAS: Jerry, tell me about yourself and what brought you to Arkansas.

JP: I am originally from Iowa. I moved to Arkansas with my family in the middle of my junior year in high school. After high school I moved around a bit – I went to college in Florida and studied art history, then I moved to New York for a few years. I had always wanted to live there, but I didn't really have goals, or any kind of focus really. I came back to Arkansas with the intention of just staying for a few months, but then I met my future life partner, and I began to develop an interest in making art. I made friends with other artists here in Little Rock and I took advantage of the fertile, nurturing community of creative people here at the time. Little Rock was really fun in the late 80s! So, then I decided I wanted to pursue graduate school, because I felt strongly about my work, but I knew it could get better if I had more direction. I had recently visited the Whitney Biennial and many of the artists had one thing in common – the California Institute of the Arts. I had some friends who had studied there, so I decided to apply. It was the best decision I could have made. Anyway, jumping forward quickly, went to California, moved back to New York after graduation, started showing my work with a gallerist who fostered my work in a very positive way, eventually realized I could be more satisfied personally if I came back to Arkansas and worked from here, so voila. Living the high life in Little Rock again!

AAS: The California Institute of the Arts is ranked in the top 5 graduate art schools in the country. What was your experience like there?

JP: CalArts was critical in my evolution as an artist. I entered the program with vague ideas about what I wanted to communicate, and why, and over the course of my studies I began to refine my ideas about what it means to create an image and put it out into the world for consumption. At the time I was very interested in the confrontational aspect of the work of Barbara Kruger, and I was fascinated by the work of Adrian Piper in terms of its ability to implicate the viewer in the act of looking. So, I went into the program with the intention of making work that would influence viewers and attempt to produce social change.

The beauty of the CalArts situation was that my expectations were consistently thwarted at every turn! It wasn't so much that my interests changed, but I began to think more about the presentation and reception of art. I also developed a much deeper awareness of my own psychology and how it informed everything I produced. So, really, it was like a two-year therapy session and I came out on the other side with a lot more tools for evaluating and interpreting both myself and the culture around me.

The program at CalArts was focused on theory, so my classes consisted of readings and discussions. For example, my painting class was called "Painting Issues" and didn't involve putting paint on a canvas. It was more a gathering to discuss current practices vis-a-vis other options for representation. So, while I entered the program with the intention of making paintings, I soon switched over to drawing so that I could produce images more quickly. And I wasn't too fussy about how the drawings looked back then. I was more interested in what was being represented, rather than how.

AAS: When did first realize you had a talent for drawing and wanted to become an artist?

JP: I'm not sure if I ever set out to become a visual artist. Growing up, certainly I was always interested in making things. But I was also interested in music and playing instruments, theater, dancing – arts-type stuff. I guess I had to find a way to express myself that would be most conducive to my personality type. I'm not hugely verbal and my relationship to language is somewhat fraught, and I have found that the most effective way for me to stake out a place for myself was through visual arts.

When I was young – junior high and high school in Iowa – I had an incredible friend who found constant amusement in the world and together we were always exploring and making things. We wrote movie scripts, made books, wrote goofy songs. We spent a lot of time wandering the stacks at the local library for new ideas. That friendship made the small town we lived in seem ripe with possibilities and I still carry the sense of wonder that was nurtured in those years with me today.

AAS: The first work of yours I ever saw was your self-portrait at M2 Gallery. It is a stunning drawing. What does it say about you?

Self Portrait, 13” x 10”, graphite on paper

JP: Thinking of myself as the product of encounters and influences, I constructed a self-portrait that reflects an amalgam of fragmented interests. To be a true representation of self, this composition would need to be continuously transformed as new encounters are incorporated into my artistic DNA, but for this piece I chose to represent myself as the sum of these parts (from left to right): the bemused Ernest Thesiger (the actor who portrayed Doctor Pretorius, creator of the intended bride in the eponymous "The Bride of Frankenstein"); my best friend John, who is the ideal with which I measure a successful life; German actress Hanna Schygulla (in my mind the epitome of self-possessed cool); my hometown girl Jean Seberg in a still from the film "Breathless" by director Jean-Luc Godard (whose thoughts on filmic montage and the power of images are a constant source of inspiration); philosopher and social satirist Voltaire, who reminds me continually to "cultivate your garden;" my great friend Enzo, who radiates freshness and spontaneity and compels me to look at the world in unexpected ways; Japanese anime character Tetsuo (from "Akira"), a juvenile delinquent who develops technopathic powers after being subjected to covert scientific experiments; and, lastly, Frankenstein's monster (as portrayed by Boris Karloff), whose cobbled-together form best represents my ideal conception of self.

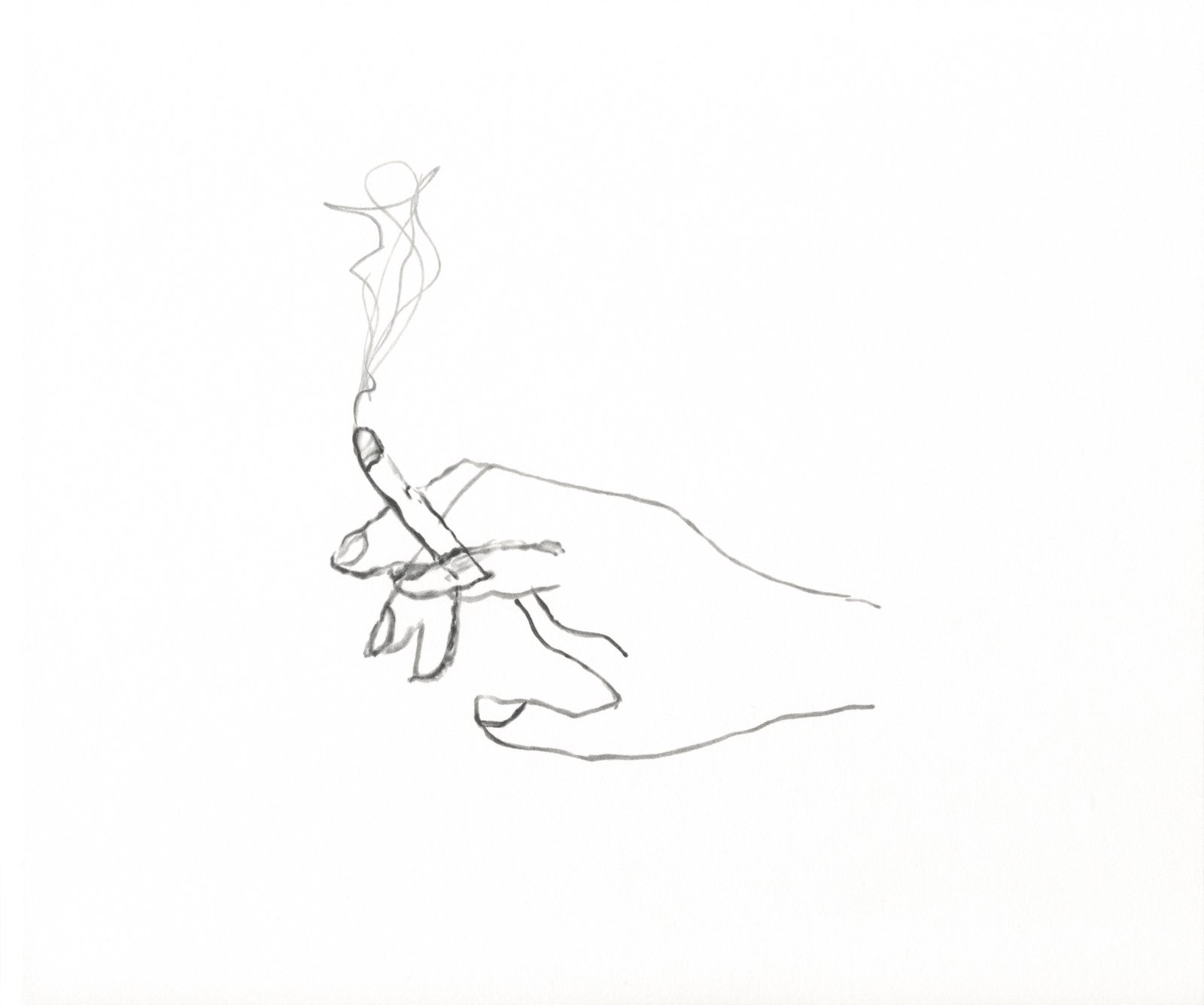

AAS: Many of your drawings have an ephemeral look – like they are drawn in smoke. One example is the woman floating within the architectural piece. It is marvelous work.

Untitled, 8” x 9”, graphite on paper

JP: With this drawing, I layered several images on the paper to suggest an elusive dialogue. More often, I present the drawings in salon-style groupings where juxtapositions invite the viewer to intuit meaning through proximity. This has been my primary occupation throughout my career and I truly believe that through these visual setups we can find freedom. Interpretive freedom, if you will. Because so much of the way we consume images is largely mediated by those in control of dissemination. I want to create an arena where the viewer is the agent of interpretation. With this piece I placed the elements on one page so that the conversation is contained within the frame. In a sense, the visual elements waft over and through each other and the linkage feels more suggestive and intimate.

AAS: How do you achieve the powdery smokey look to your drawings?

JP: This technique has evolved considerably over time. As I mentioned, in graduate school I was really just whipping them out. Eventually, I found myself focusing increasingly on the application of graphite as a method of seduction. Over the years that surface has become more and more burnished as I start with softer pencils, then add to the surface using harder pencils. My technique has always been a contentious subject for me. I try to retain a sense of neutrality with the medium so that it doesn't get bogged down in "mark making" which isn't something I want to explore much. But admittedly this is a kind of marking and I can't completely disavow the craftiness of it. When I began drawing, I had no interest in issues of style, but over time this technique has evolved organically, and it has snuck up on me. And I admit that the graphite work can be a useful method for convincing people to take a closer look.

AAS: You have drawings in museum collections around the world including these two at MoMA. Tell me about those two pieces.

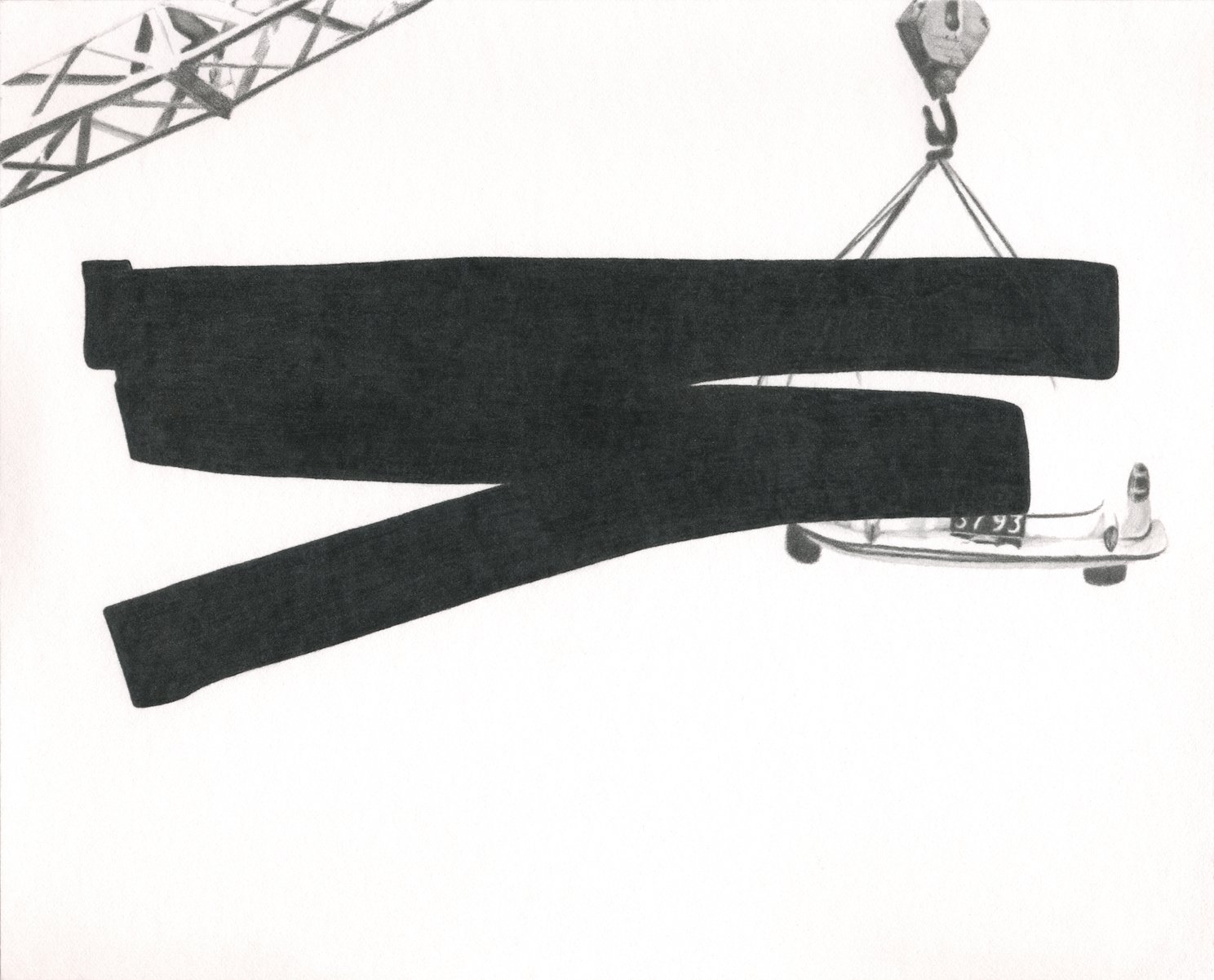

Untitled, 6.5” x 11”, graphite on paper, collection Museum of Modern Art, New York

JP: These two pieces were part of a body of work that hinted somewhat vaguely at ideas about suburban idylls and the David Lynchian forces at play behind the facade of contentment. My work is largely a collection of found images (usually photos, but also sometimes handwritten texts and drawings) which I then draw and assemble into groupings that are hung to suggest a quasi-narrative which is really more of a visual poetic essay than a thesis. In this particular collection, I combined images from newspaper photos of "this week's top real estate sale," an explosion from a still from "The Bride of Frankenstein," a portrait of one of the Manson family members, and other sundry finds. These two drawings were based on an internet image of a landscape with sunrise and of an image from an automotive magazine. The 'heads' to me suggested four faces gazing out at the viewer and added an anthropomorphic paranoia to the overall grouping. The pieces were selected as part of an acquisition by a museum donor who made the purchase with the assistance of the director of the drawings department at MoMA.

My work came to the attention of MoMA through my affiliation with a gallery called Feature Inc. in New York. In the international art world Feature was known for its innovative, individualistic and unconventional exhibition program. I was introduced to the owner/director, Hudson, by one of the CalArts faculty members when I moved to New York after graduation. Hudson believed in the power of each artist's imagination and he gave us all a laboratory in which we could explore our individual worlds without concern for mainstream acceptance or market validation. He didn't follow art world trends and certainly didn't believe in setting them. If he believed in the work, he would support it without reserve. As a gallery artist, this allowed me a great deal of latitude because I wasn't required to produce work to meet market expectations. And collectors were drawn to the gallery because of the integrity and ingenuity of its programming. My relationship with Hudson and Feature Inc. lasted just shy of 20 years, when the gallery closed suddenly after Hudson's untimely death. The memory of his unbridled curiosity continues to inform my daily practice.

Untitled, 5.5” x 22”, graphite on paper, collection Museum of Modern Art, New York

AAS: Your drawing in the collection of the Museum Overholland in Amsterdam is a wonderfully organic piece. Tell me about that piece and your connection with Museum Overholland.

Untitled, 19” x 12”, graphite on paper, collection Museum Overholland, Amsterdam

JP: This piece is in a way, quintessential. It's based on a small fragment of a found image and it was drawn after being manipulated in the computer. I don't necessarily like to give the source subject away, because I prefer the drawing to occupy an undefined space in between realism and abstraction, but for the purposes of this interview let me say that the source was a fashion advertisement for Christian Dior and I chose it for that organic quality, which was heightened even more in the rendering process.

This piece is one of eight in the collection of the Museum Overholland. The director of the museum was unique among collectors in that he often came to see the work in my studio in New York. His engagement with the drawings was satisfying because he enjoyed talking about the entire process - the image hunt, the manipulation, my relationship to content - he connected in a way that was, of course, what any artist would hope for.

AAS: You also have three drawings in the La Centre Pompidou collection in Paris. How did you develop a relationship with them?

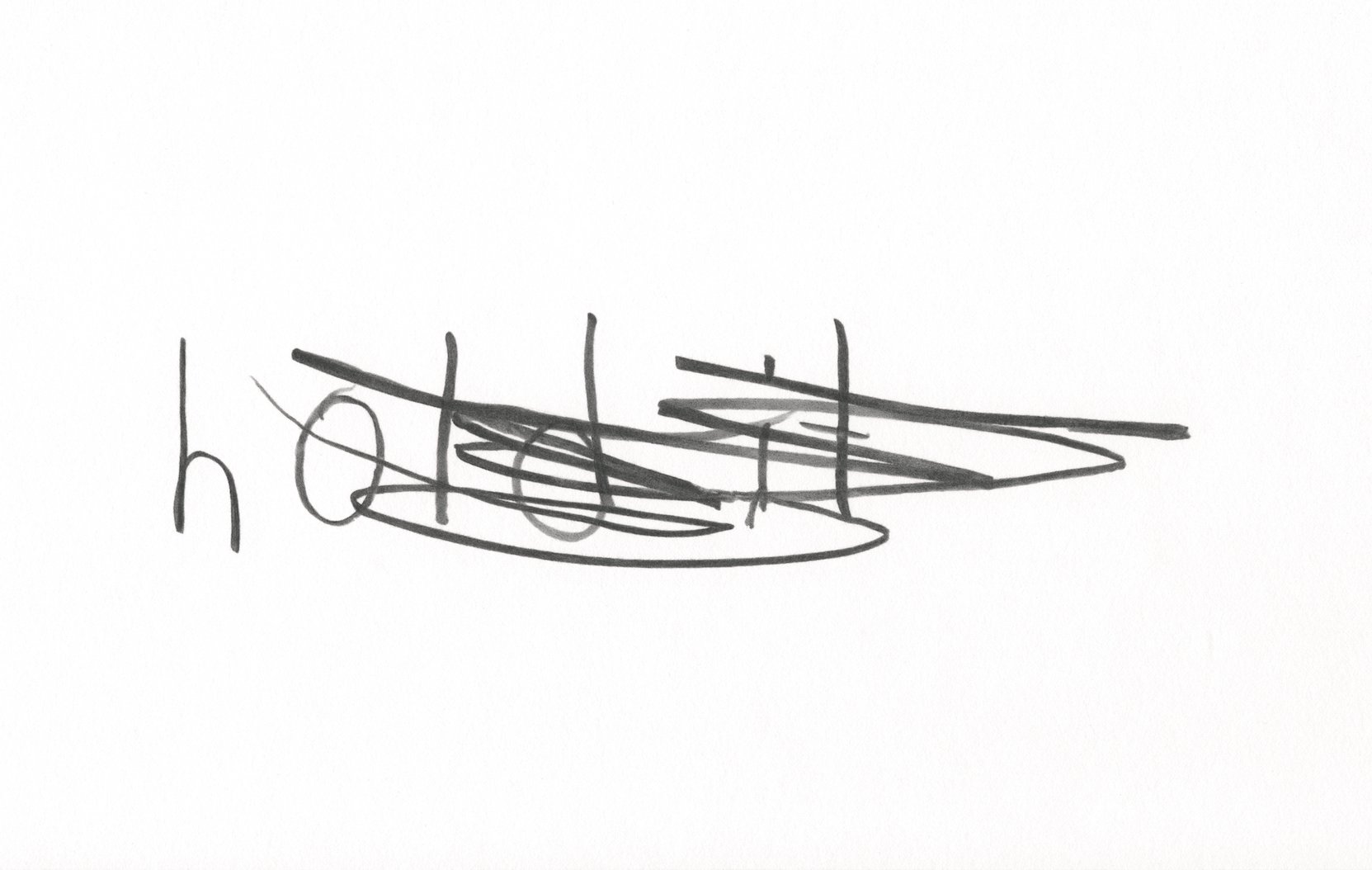

Untitled, 28” x 20'“, graphite on paper, collection Centre Pompidou, Paris

JP: One of the drawings in the collection of the Pompidou is an enlarged rendering of a scribble taken from a piece of scrap paper I leave next to my pencil sharpener. I always make a little scribble with my pencil after sharpening to get rid of any sharp jaggies on the tip, and I took one of these marks and copied it so that it appears to be a large version of the original. When closely examined, it is clearly a painstaking recreation of the original but drawn using graphite layers to form the delicate lines. I find that using labor-intensive processes to reproduce spontaneous gestural moments pleases me in an absurdist way, as it creates a tension between the implied importance of such a commitment of labor and the whimsy of the throw-away subject matter.

The scribble wasn't like anything I had done before and I wasn't sure how it would be received. The acquisition of the drawing to an important collection was a personal validation that gave me a boost in terms of trusting my instincts. The other two drawings in the Pompidou collection are equally playful. One is a somewhat abstracted drawing of pig's feet from photo of a meat market display, and the other is a detail from a perfume ad depicting a fragment from a floral bouquet that is almost post-apocalyptic in appearance.

The drawings made their way to the Centre Pompidou via a gift from the Guerlain Foundation, which houses an extensive drawing collection in France.

Untitled, 11” x 11”, graphite on paper, collection Centre Pompidou, Paris

AAS: Your drawings are incredibly diverse. Where do you get your inspiration?

JP: I have an affinity for the ragpickers of old who scavenged through discards looking for items of value. There is a high degree of randomness to my project in that I often don't know what I will use next until it presents itself, often haphazardly. The library is a big source of material because I still enjoy spending hours wandering the stacks as I did as a child. The internet is sort of good, but actually it's easier to find images on the internet if you have use parameters and I prefer to allow for more of an aspect of chance. For example, boxes of ephemera at flea markets can yield surprising visual gems. And like many a good flaneur, I find amusement from whatever piece of cultural detritus crosses my path. At the same time, in the midst of assembling a new collection I may have an idea for a type of image that will add to the mix in a desirable way. I have boxes and stacks and folders full of scraps and clippings, and I have a good memory for what I've collected. I might think of something I saved years ago and realize that it fits with whatever grouping I am currently working on, and usually I can go straight to the place I've saved it. Given that my practice is largely additive, I am always thinking about how each new piece is an attempt to engage with past work and to articulate something new to those pieces that came before.

AAS: What can we expect next from you?

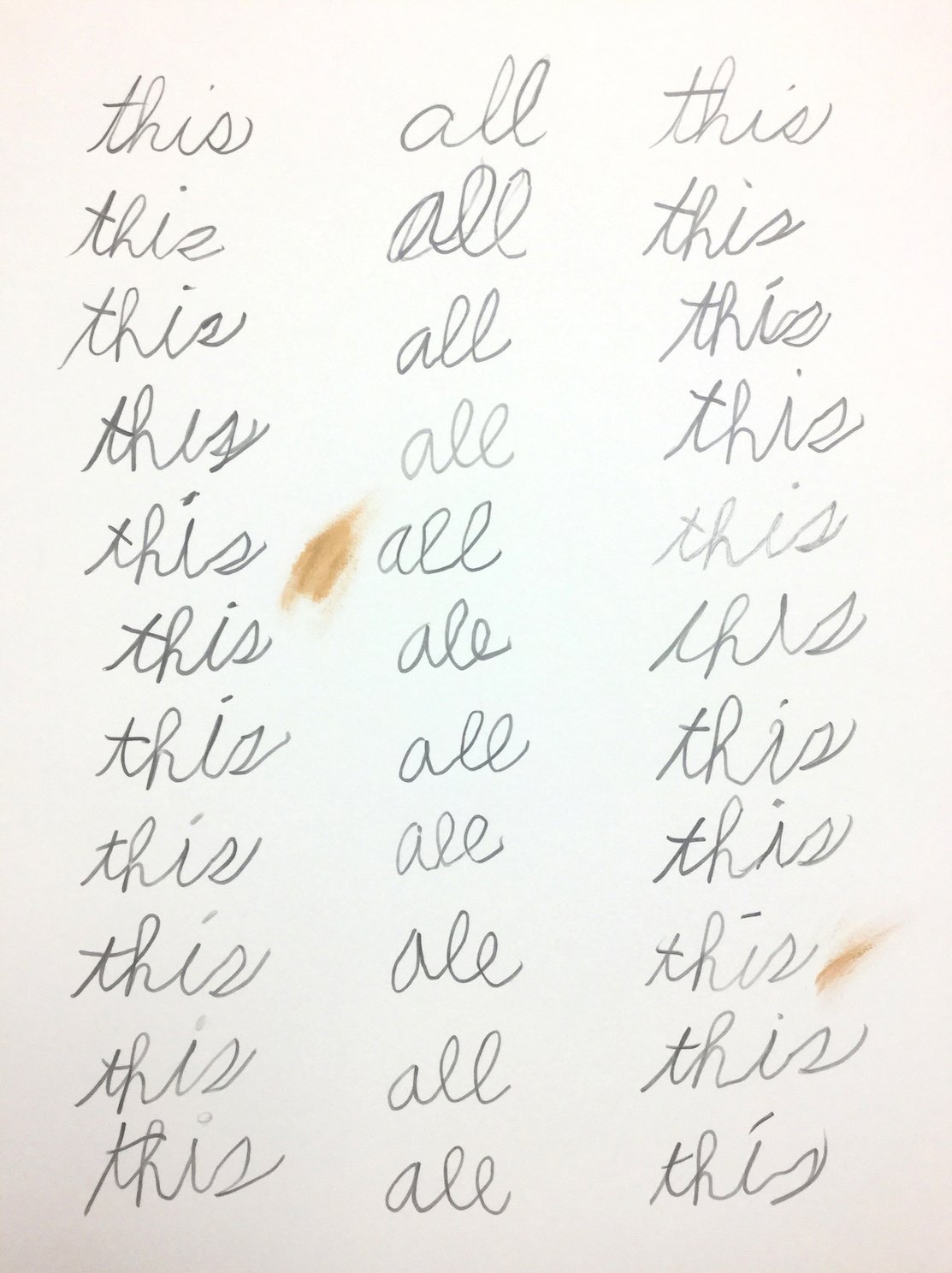

Untitled, 16” x 16”, graphite on paper

JP: Recently, I have been studying reconsidered texts from historical manuscripts. Just before Covid hit I had an opportunity, with help from a grant from the Arkansas Arts Council, to visit the Morgan Library in New York. There I was able to examine and photograph original edited manuscripts by Edgar Allan Poe, Walt Whitman and Oscar Wilde. I focused on excerpts where extensive edits had been made, as my interest was in trying to understand each writer's thought process as a generative, protean practice. Ideas about revision and rethinking have been going through my head, so I have been making some work that directly quotes from other people's manuscripts and sketchbooks. I often utilize quotation as a strategy to initiate a dialogue with the remnants of others, and these drawings represent an attempt to convey my identification with their processes. I relate this to the practice of many artists who take sketch pads to art museums and spend hours copying the work of the old masters on display. It brings one into an uncanny moment of identification that I didn't fully understand until I tried it myself.

So really, what comes next is largely a result of whatever I stumble upon, which is the beauty of the open text - it can go anywhere and, hopefully, will spark many new conversations.