Interview with artist James Volkert

James Volkert is an artist living in Conway, Arkansas. Originally from Minnesota, he earned a BA in fine arts from the University of California, Davis, and an MFA from the ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena. James has always been fascinated by museums and after college, he worked for 35 years in museums including 20 years at the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. He also taught exhibition development at George Washington University for 10 years. His love of museums and what they represent shapes his current art practice, which is about reimagining classic paintings in unique ways to encourage the viewer to re-engage with the work in new ways. More of James’ work can be found at his website jamesvolkert.com.

AAS: James, where are from originally and what brought you to Arkansas?

JV: I grew up in Minnesota through high school. We moved to California in February of my junior year – from snow parkas to shorts in a few days. I thought we were in heaven. After undergraduate work in fine art at the University of California, Davis and graduate school at Art Center in Pasadena, I launched myself unsuccessfully into the art world with a gallery, but not a single painting sold. I moved into museums focusing on exhibitions, starting at the Junior Arts Center in Los Angeles, where I developed the gallery exhibitions – not exhibitions of children’s art, but exhibitions for families that pushed the limits of engagement and interactivity. We did a show on movie special effects with borrowed props from the studios where kids could create their own special effects magic, an exhibition of the drawings of an LA artist that used animal bones as inspiration, to which we added his collection of bones and a live horse boarded in a corral in the gallery. This experience led me to always look for new ways to engage audiences.

I moved to Washington D.C. and became the head of exhibitions for the Smithsonian American Art Museum, spearheading the exhibitions there and the Renwick Gallery. Here I could live with the great American artists – Homer, Remington, Hopper, Man Ray. Again, the exhibitions always looked to push the edges of interpretation and resulted in great experiences for me – escorting Juliet Man Ray [Man Ray’s wife and muse] to Man’s studio in Paris, having drinks with Luis Jimenez in Juarez, Mexico. I then moved to the emerging National Museum of the American Indian and built and opened their three facilities in New York and Washington. While I was teaching at The George Washington University, I met my wife, Barbara Satterfield, a ceramic artist and, later, the director of the Baum Gallery at UCA and followed her to Conway after retiring from the Smithsonian.

AAS: Were you exposed much to art growing up?

JV: There were a few key moments growing up. I had an art teacher in high school, Mr. Hansen, that recognized my growing interest in painting and gave me great latitude to explore media and push limits. UC Davis was abuzz with artists when I was there. I took classes from Wayne Thiebaud and Robert Arneson, met Richard Diebenkorn and Sam Francis, and interviewed Hans Hofmann and Peter Voulkos. I knew I wanted to always hang around art and museums.

“Museums are awesome spaces, or awe-full places. Walking up to objects that have witnessed history and are just itching to tell you their stories is an amazing experience.”

AAS: What do you think it is about museums that excited you as a kid and still now as an adult?

JV: Museums are awesome spaces, or awe-full places. Walking up to objects that have witnessed history and are just itching to tell you their stories is an amazing experience. Too many museums miss the opportunity to make this connection. But when museums succeed in unwrapping the layers around the object, when they understand what you, the visitor, is bringing to the encounter, when they take you by the hand and are your perfect companion for the visit, they provide memorable experiences that are unique and powerful.

AAS: I would like to ask you first about Lost: After Rembrandt. It is a beautifully painted version of Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee. What was it about the history of this painting at that inspired your tribute?

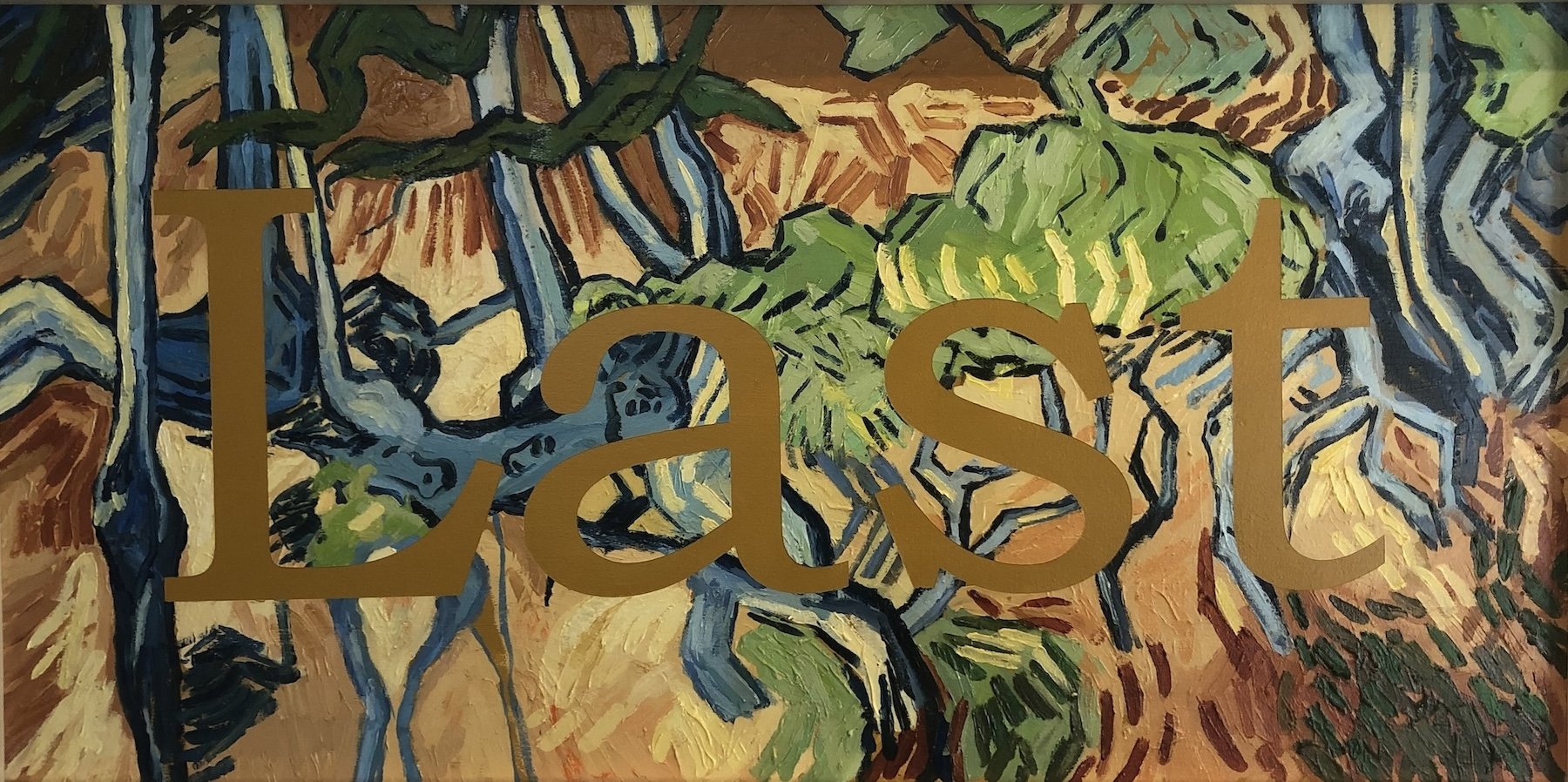

JV: In thinking about creating multiple avenues for viewers to engage with artworks, I began looking at incorporating words and language to play off familiar images. The first was a series of three pieces called Lost, Last, Lust. I thought the Rembrandt painting was perfect for Lost because of the plight of the disciples in the boat and the fact that the painting itself remains lost, stolen from the Isabel Gardner Museum in Boston in 1990.

Lost: After Rembrandt, oil on linen, 20" x 40"

AAS: Your painting Night Lights: After Hopper is wonderful. It must be fun reimagining great works of art in the hand of the original artist.

Night Lights: After Hopper, oil on canvas, aluminum plate, 25” x 31”

JV: I have always loved art history as a window into another world at another time. Most of my museum visits are spent inches from the painting reveling in the paint connected to the brush, connected to the artist’s hand, connected to the artist’s mind, an instant in the past. For me, it about looking carefully at the painting and its intent, but also trying to understand the artist’s process. What did they do first? Exactly what is the sequence of making the work?

AAS: You wrote that “making art for me is about making objects, the perfect combination of museum and hobby shop.” Can you elaborate more on that? I guess your experiences as a kid had a lot to do with what your art practice has become?

JV: I have always built things. As a kid, I built model airplanes, cars, boats. Every Saturday I would spend all afternoon at the Robert St. Hobby Shop in St. Paul, maybe to the annoyance of the owners, looking at every model over and over – particularly the built examples in the cases. They were perfect objects. How did they get the flat finish, or the camouflage so perfect? Oh, and I would usually buy a 19-cent stick and tissue model to build the following week. It really instilled a kind of reverie for beautifully made things. Models also had a life cycle. After sitting on the shelf for a time, they were meant to be played with – flown on imaginary trips, sailed across stormy seas, raced around the track. It let me know that beautiful things could also be played with.

AAS: Tell me about Difficult Passage: After Turner. Why did you choose to interpret that painting into one that is interactive?

Difficult Passage: After JMW Turner, oil on canvas, wood, brass, 36” x 36” x 10”

JV: I had been looking carefully at JMW Turner and saw his Calias Pier, 1803, and was taken with the power as the ferry arrives under heavy seas. As a sailor, I have been in situations where the sea is in command. I wanted to make the painting into an object that conveyed this power. The image is cut into 30 narrow strips, each sequentially driven up and down by cams and a hand crank at the bottom so the ships and seas rock and roil. I have always been fascinated with antique toys that create movement with gears, rods, and cams. The piece is now owned by a collector in Florida, so it is closer to the ocean, as it should be.

AAS: Another of your interactive pieces that I really love is Examination: After Eakins. Coming from the medical field, Gross Clinic has always been one of my favorite paintings. Yours it is so cleverly executed.

JV: I am drawn to paintings that have an embedded narrative and drama. This Thomas Eakins painting is rich and potent, both because of masterful painting of an anatomy lesson and the critic’s reaction to it as “vulgar”. Much like the instructor in the painting would have said, “Look closely at this”, I wanted the viewer to look carefully, to “examine” parts of the painting. The whole piece has the character and finish of a 19th Century medical tool.

Examination: After Eakins, oil on canvas, steel, brass, convex and concave lenses, 34” x 20.5” x 5”

AAS: Evidence (water): After Eakins is another fun piece, beautifully painted and with added ‘realism’. I have to ask the origin of the water, but I suspect it is from the authentic location? How much planning goes into your pieces?

JV: The whole Evidence Series looks to raise questions about what do the words “real” and “authentic” mean. Each painting is overlaid with an actual object collected from the place depicted in the image to get the viewer thinking in those terms. So a Georgia O’Keeffe piece is overlaid with air and earth collected from her studio site in Abiquiu, NM. In Evidence (water), the water is collected from the actual site of the race on Schuylkill River in Philadelphia.

Once I decide on an image, I either collect the objects from the site myself, or have someone from my network of museum friends who live near the site collect with very specific instructions: a gallon of water, a pound of earth, rocks, etc. from a very specific place. It is also amazing what you can find on the internet. You can order a stone from Jerusalem and water from the Jordan River!

As I approached these pieces (and really all pieces) I generally know the intended outcome and work toward it, always measuring the results with the ideal in my mind. This allows me to go forward with the painting while waiting for FedEx and UPS to bring me wonderful things. Having worked decades in museum exhibition production, I love the intricacies of making little brass mounts or figuring out how to attach the glass vials to complete each work.

Evidence (water): After Eakins, oil on canvas, water from the Schuylkill River, glass bottles, wood, 18" x 36" x 6"

AAS: Strong Onshore Breeze – After Homer is brilliant! I know your work has been exhibited around the country. What kinds of responses do you get from your work?

Strong On Shore Breeze: After Homer, oil on canvas, wood, 18” x 24” x 8”

JV: This is one of my favorite pieces! Winslow Homer was an illustrator and painter and all of his work has a story embedded in it. When I first saw his work, Long Branch, New Jersey (1869), I could almost feel the strong, sunny onshore breeze along the promenade. As I thought about how strong could it be and how could I have the viewer sense the same thing. Could it be strong enough to curl the canvas back? The playful side of me said yes.

Apparently, some viewers felt the same. This piece was on exhibit in a museum in Ft. Worth and a concerned museum visitor came up to the gallery staff and asked if they knew that one of the paintings was damaged and coming off of its stretcher bars!

AAS: Arkansas is fortunate to have many wonderful museums in different locations throughout the state – in addition to Crystal Bridges and Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts. And you have been very involved in developing exhibitions, especially for children. Are you at all concerned that the next (or current) online generation may miss out on the experiences you had at museums as a child?

JV: Honestly, yes, I am concerned. Some museums are trying take on the media challenge and outdo each other to see who can become the most immersive – van Gogh in 4D! or 5D! I think this is the wrong path. Visual Reality and Augmented Reality can be useful tools but are a kind of “sugar high”. You saw the precursors of that in watching children race around children’s museums to see how fast they can turn cranks. It’s really just action rather than absorption. For me, it comes back to finding ways to make the objects sing and tell their stories in a way that brings you right up beside them as they whisper in your ear.

AAS: Tell me more about your work in museums and serving as a curator.

JV: Over my 40 years working in museums, I have overseen the development, design, and installation of more than 400 exhibitions. I have worked both on staff and as a consultant nationally and internationally, always with the intent of figuring out how to engage visitors with the content.

I started working at the National Museum of the American Indian in the very early stages of the project to help imagine a fundamentally different kind of institution that brought forward Native thinking and voices to reveal their perspectives on the world, their histories, and objects. The museum is based on a New York collection of more than a million Native objects. The Smithsonian took over the collection with the provision that they build three facilities: a museum in New York, a collection facility outside of Washington, D.C. and a museum on the National Mall. I oversaw the architectural and exhibition design for all three. The George Gustav Heye Center opened in New York in 1994 in the historic U.S. Custom House building on Broadway as a permanent exhibition and program facility; the Cultural Resources Center opened in 1999 as a home for the collections and place for Native people to research and visit their objects (we moved the objects from New York to D.C. with a full tractor trailer every week for a year); and the museum on the National Mall opened in 2004 with a celebration and 30,000 Native people in attendance. My work afforded me the opportunity to travel the Hemisphere and see the Native world from the inside.

My museum career has been wonderful. As a consultant, I have had the opportunity to oversee exhibitions throughout the U.S., in the Middle East, Europe, and Central and South America. I have worked with the amazing staff at National Museum in Kiev, Ukraine in 2018 to imagine a new museum dedicated to their revolution of independence from Russia. All the staff were veterans of the Movement and are now collecting objects for the museum at the front of the current tragic war.

But Argentina has my heart. Over 30 years and in concert with a foundation in Buenos Aires, we developed a training program in exhibitions for museum professionals that brought together 30 participants from around the country to imagine, design, build, and open an exhibition at the host museum. We repeated this 10 times at different institutions around the country and trained over 300 museum staff in rethinking how exhibitions could be presented where visitor engagement was the priority.

AAS: James, are there any other famous works of art that you are planning to tribute? What can we expect from you next?

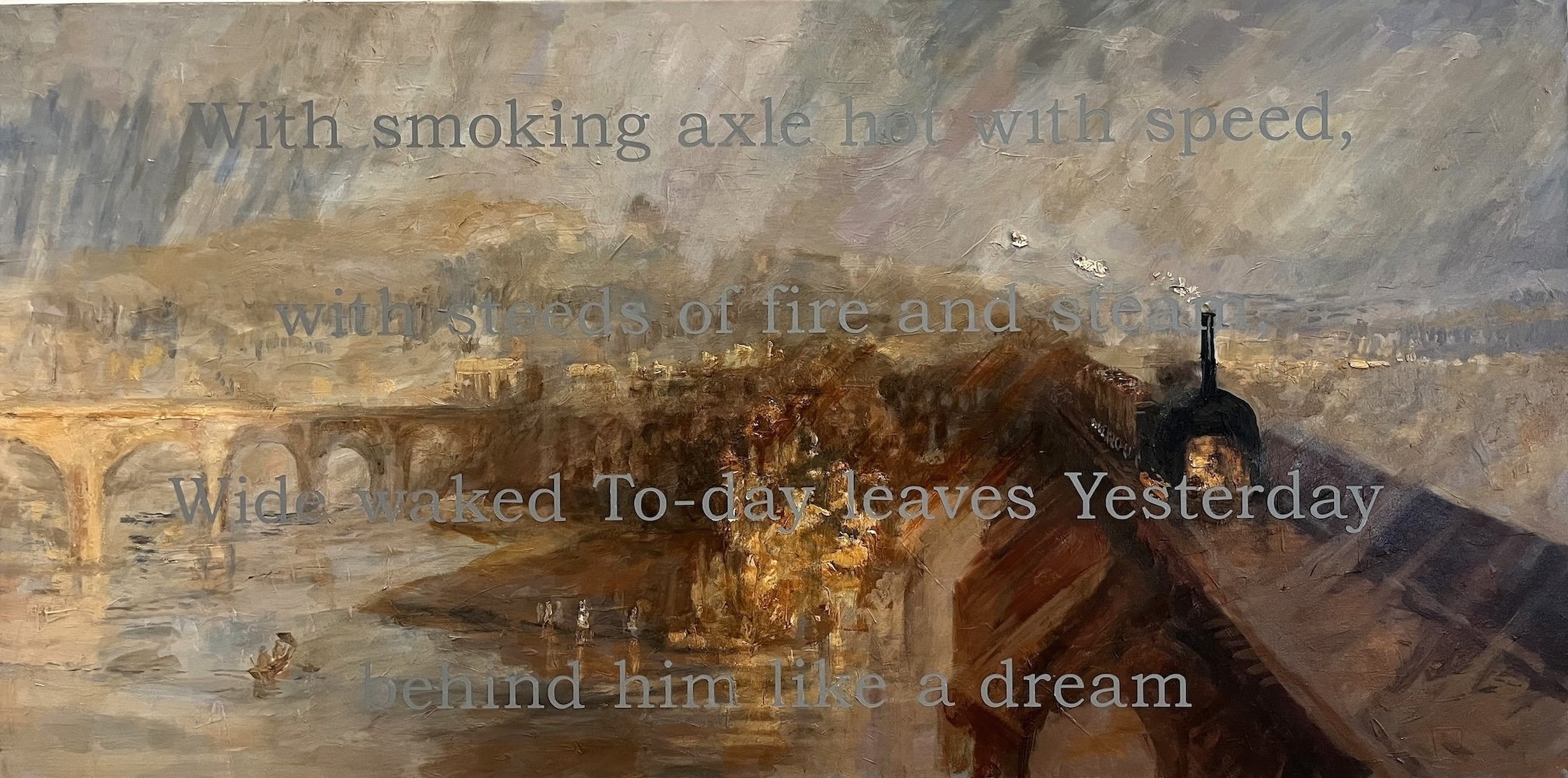

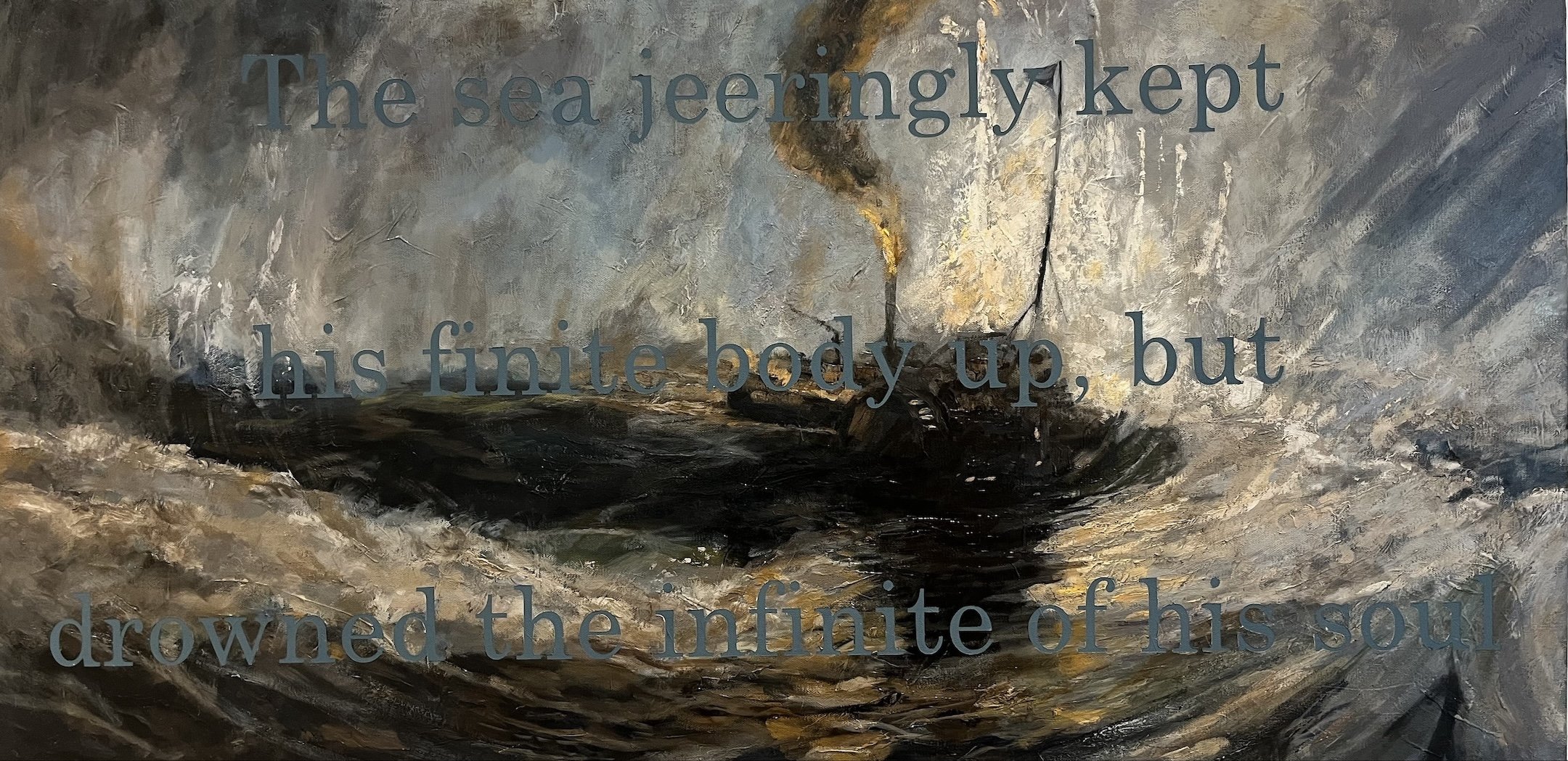

JV: I have begun to think more about working in series, making multiple pieces around the same idea. I have completed the Evidence Series and a series that combines the work of JMW Turner and quotes from literature.

Right now, I am working on a series of to-go boxes, or more accurately, To-Gogh boxes that combine a wooden box with a familiar painting by Vincent with an action figure of van Gogh from a now-defunct company I had called Fine Arts Action Figures. So, the play continues!