Interview with artist Heidi Carlsen-Rogers

Heidi Carlsen-Rogers is an artist living and working in Northwest Arkansas. She used floral photography, tapestry, and thread to create oversized gardens that seem to magically spill into their environment. Heidi is a recipient of grants from the Walton Family Foundation - Mid-America Arts Alliance, and from the Arkansas Arts Council. Her work is one of three artists in the Arkansas Women to Watch: New Worlds 2023 exhibition, by the Arkansas State Committee of the National Museum of Women in the Arts touring throughout the state. More of Heidi’s work can be found at her website heidicarlsenrogers.com.

AAS: Heidi, tell me about your background. Where did you grow up?

HCR: Most of my time growing up was spent in Ohio, so I experienced a very Midwestern perspective in terms of place. I was actually born in Alabama and my family is originally from the East Coast (New York and Connecticut). We spent time in the northeast visiting family as kids, so there was always a mixing of perspectives, environments and “ways of being” in those different parts of the country that still influence my work as an artist today.

I attended Kent State University and after graduating worked in the corporate visual display and retail design industry in Cleveland, Ohio. My husband and I spent several years living in Chicago before moving to Northwest Arkansas in 2007.

AAS: When you were a kid, did you ever think you would one day be a full-time artist?

HCR: That’s an interesting question for reflection. I lived in a very non-creative household with little art exposure early on, but I was an extremely observant, curious, and creative kid. At a young age, I was always getting into trouble for re-arranging furniture, collecting things I found outside, putting together wild outfits, making messes – my creative spurts were not really embraced or encouraged!

Once I was in school that changed, and I was able to create more freely in art classes. There was a pivotal experience in my early teens that was the first real inkling of becoming an artist. When visiting relatives in Washington DC when I was about 12, we went to the Phillips collection. In the gift shop I saw a print of Georgia O’Keeffe’s Red Hills – which was an abstract painting of the landscape. I couldn’t stop looking at that print and ultimately talked my parents into getting it for me. That artwork hung in my room and haunted me until I left for college. I studied it obsessively and felt an affinity for the artwork even though I didn’t understand abstract art or what it was about. It felt serendipitous, you know?

In my teens I was also drawn to fashion magazines like Vogue during a time when fashion photography was becoming more avant-garde. This was pre-internet, so the only way to gather new information was at the library and I felt like magazines were a portal to another world. I think this shaped much of my visual aesthetic and sense of possibility.

Later in life, I had two significant mentors, one in the art world and the other a non-artist. During my time working on the corporate side, I had a boss who was extremely entrepreneurial, very visionary and went against the corporate grain – a risk taker. He used to tell me, “Always say “yes” to a client request even if it seems impossible and then trust you can figure out how to make it happen”. I’m not sure if that is solid advice in retrospect, but it did build my muscle in problem solving, creative thinking, determination, and willingness to try impossible things that I’d never done before. His example of working with an entrepreneurial mindset and way of operating in the world has served in my creative practice over the years. Computer aided tools were not readily available at that time, so pieces had to be made by hand – hand traced and lettered, designs cut and glued together - one at a time. In that, I learned how to build and construct things from the ground up and understand how things are made – an invaluable skill in the studio. And understanding how to approach and execute large scale projects has been another skill that has translated to my art practice.

In college, my abstract painting teacher was the first person to really advocate for my work and was instrumental in introducing me to artists like De Kooning and Joan Mitchell who were pivotal in embedding the ideas of pure expression and the pushing back of painting conventions at that time. I will always be grateful for how he challenged, encouraged and supported me to push forward, think more broadly and not give up in frustrating art moments!

AAS: Do you think relocating from a more urban environment to Northwest Arkansas has shaped your work?

HCR: Moving to Northwest Arkansas from Chicago 16 years ago, really shifted not only my environment, but expanded my perspective on many levels. There is a beautiful rhythm in Northwest Arkansas and the Southern culture that I’ve experienced. Slowing down, savoring of the moment, and living in close proximity to the natural environment helped be more present to my surroundings, absorb the ebb and flow of the landscape and hone my observation skills as an artist.

Gaining the ability to notice details, especially in nature, that I would have previously overlooked has become catalyst for my work. I especially love the openness and the willingness for people to take time and share their stories. This influenced my own daily writing practice – helping me dig into a deeper well of reflection and creative resource that I hadn’t plugged into prior.

Specific to Northwest Arkansas, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art opened in 2011 – less than 10 miles from my art studio! I had the privilege of being part of the inaugural gallery guide program at the museum and having intimate access to world class art and artists has been aspirational and pivotal in developing my creative outlook and voice. I don’t believe the flower tapestries would have come to fruition if I had lived in any other location – in a sense they are kind of “Arkansas grown”!

“There is always hidden meaning embedded throughout my work, a deeper story beyond the surface.”

AAS: Your recent work combines photography with tapestry and thread – and the thread is seemingly used in almost a painterly way. Is there a connection or reference to painting in your textile work?

HCR: For the first 12 years of my art practice, I was a painter, which has had a big impact on how I see and approach this tapestry work. Color, rhythm, and line were important elements of my paintings that translated into how I use the thread today. I hand select and combine thread colors together as I stitch, mixing the strands together creates the impression of custom, hand-mixed colors. And similar to mixing paint, I am able to create subtle shifts in hue, tone, chroma. And thread happens to come in an incredible and intoxicating range of colors so there are infinite possibilities to work with! The way the flowers are photographed and arranged, and thread placement decisions are all approached from a painter’s perspective as well.

AAS: I want to ask you first about Undone from your Meet Me in the Garden series. The way you’ve used pooling thread is wonderful. Tell me about that piece.

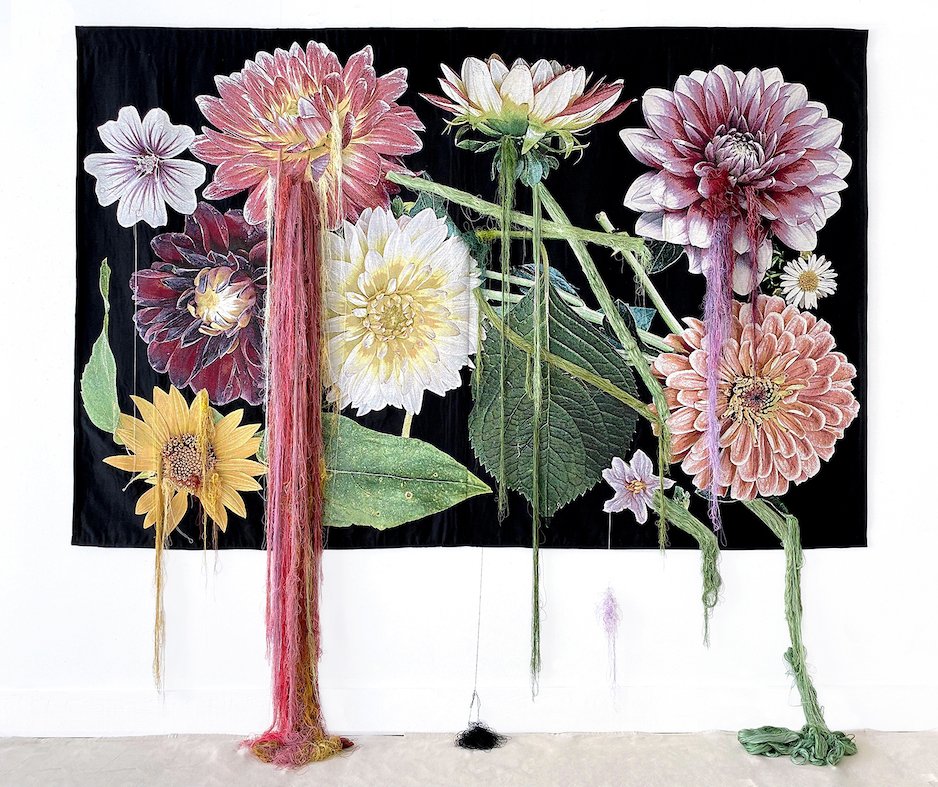

Undone, 91” x 101”, photographic woven tapestry, cotton, polyester and viscose thread

HCR: Undone was one of the completed artworks for my Artist 360 grant project Meet me in the Garden. It’s an 8’ x 8’ tapestry and in the work you can see human-sized flowers with thread spilling from the centers and edges of petals and as you mention, thread pooling into piles on the floor.

There’s an overarching theme in my textile gardens that reflect my concerns about the wellbeing of our society and planet, increasing fragmentation and growing lack of empathy. The tapestries are symbolic of our weakened natural, social, political and emotional environments. I see them as one blurred and interconnected “landscape” - all fragile, unravelling and in need of care and solutions for repair. The flower tapestries with thread spilling out are a metaphor for what I observe coming undone in our world.

In Undone, there are flowers with missing petals, faded flower buds and weeds that are situated beside perfect blooms. The traditionally excluded or unvalued from a gardening perspective are given a place of equal importance. There is always hidden meaning embedded throughout my work, a deeper story beyond the surface. For example, I was thinking conceptually about the threads as they fall downward and how they can never be rewound to their original state. And how thread, in its most basic function is made to mend and repair things – it re-connects what is torn. The fallen threads and piles are considered remnants - symbolic of what remains from what has been damaged in our world and what’s left to work with as we mend and repair it. Thread represents or expresses the problem or unravelling I see in the world – but it also represents the solution for repair.

Heidi in her studio working on Undone.

Flower and color choices are intentional and also hold meaning. The white zinnia symbolizes friendship, endurance; blue hydrangea: regret, apology forgiveness; yellow tulip: cheerfulness and hope; petunia: contrasts both a soothing nature and resentment or anger. The piles (remnants) with their primary colors, suggest a palette, when combined, can create unlimited possibilities for something new to emerge.

AAS: You mentioned the Artists 360 grant from the Walton Family Foundation and Midwest America Arts Alliance you received in 2021. Tell me about that grant and how has helped you.

HCR: The 360 grant award was definitely a critical piece in the development and advancement of my current work. The Meet me in the Garden tapestries were part of my proposed project. Without the grant, I wouldn’t have been able to produce work at such a large scale and test my concept in such a fully realized way because the cost of materials is prohibitive. Right in the middle of my project, I ended up needing an industrial sewing machine to finish the pieces – this was totally unplanned. It would have been difficult to acquire that equipment without the funding the grant provided. It allowed me to keep working and alleviated the financial pressure of self-funding.

I have such gratefulness to the generosity of the Walton Family Foundation and Mid-America Arts Alliance. The award really was life-changing and pushed my work forward at an accelerated rate. And the ongoing peer and development support has been immensely valuable.

Unexpectedly, as the works were being finished, I was contacted by curator Chaney Jewell and invited to be part of the Arkansas State Committee of the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Women to Watch: New Worlds exhibition 2023, which is happening right now. Two of my 360 grant tapestries have been travelling around the state of Arkansas this year – it’s been amazing to meet and connect with students, curators and communities statewide. That never would have come to pass without the grant award. I highly encourage any working or student artist in this region to investigate the grant and apply!

AAS: In Unravel and Fade from your By a Thread series, you used thread as rays of colored light. It is a fascinating work.

Unravel and Fade, 51” x 58”, photographic tapestry

HCR: I love that you see the thread as rays of light! This is an earlier piece where I was writing about the idea how I felt things had been coming apart “one thread at a time” – which made me think about unravelling. I wondered if I could represent that visually and planned to unravel a tapestry literally “one thread at a time”! This took about five weeks to de-thread and then several more to reconstruct the remaining piece because it had become super fragile. I think I listened to 50 podcasts while working on this – it was a slow process!

AAS: Your tapestries are about destruction or maybe construction – I like the way that is left open for interpretation.

HCR: That’s a great observation! Embracing the idea that beauty and destruction are happening at the same time in the natural and human world is challenging. I often talk about my work as holding space for the “beautiful/terrible” – a term I use to encompass the truthfulness of what I see, beauty alongside reality, which to me represents a more complete, wholehearted picture.

In my flower tapestries, you see blooming next to dying flowers, perfect blossoms with insect eaten leaves, broken stems, torn petals, weeds, bugs on wildflowers. I find them all to be incredibly lovely and perfect in the state they are in. In my mind, they are equally important and worthy of celebration. This is my way to make the gardens panels inclusive, as the flowers stand in not only for nature, but people, our society.

In my process, you can see dismantled or deconstructed areas along with additive threads and stitching on the flower imagery. One is an act of “undoing” the other intended as a gesture of mending. A question I was reflecting on when I first began this work was: “Are we contributing to the mending or fraying of our world?” That question kind of became the two conflictive spaces I’m working from in the tapestries.

AAS: In Garden, you printed your flowers on metal and have the gorgeous threads pouring out like a waterfall. I especially like the contrast in materials and textures. Tell me about that piece and your techniques for printing.

Garden, 62” x 30”, photographic print on aluminum, sild, viscose, cotton and polyester thread

HCR: Garden was my first finished thread artwork, completed in 2019/2020 – I was still figuring out materials, concept and experimenting with process at this time. The tendrils spilling out from the center of the piece, as if nature itself is unravelling, are comprised of hundreds of yards of silk, cotton, and rayon thread – each is hand-mixed, and color matched to the flowers in the photograph; up close you can see the subtle shift in thread colors. The thread was essentially stitched into the metal.

I was trying to create a sense that flowers themselves or the environment around the flowers are weeping or disintegrating – so I love that you thought of a waterfall! This ended up being a one-off test piece essentially as I was envisioning woven textiles with thread in my mind and immediately shifted towards figuring out how to develop my concept in tapestry.

AAS: In After, you use a very different color palette and the entire effect is lovely. Is this a new direction in your work?

After, 51” x 64”, photographic woven tapestry, cotton, polyester and viscose thread

HCR: Yes! This is a new direction I’m heading in this year – a new garden series with brightly colored backgrounds and working at a larger scale as well. I’m looking to use color and light to influence emotional response, induce rest, calm – a focus on healing colors. I’m also experimenting with applique techniques and material dyeing to create new backgrounds.

AAS: Heidi, what can we expect from you next?

HCR: Building bigger textile gardens with giant flowers is at the top of the list! I’m in conversation about having a solo exhibition next year where I would be able to create an immersive garden installation – which I’ve been wanting to do. And with that opportunity would be a chance to interact and work with a new community, which is a gift – so more to come on that! Also, I’ve also been doing research on ecotherapy which is basically how nature or images of nature can facilitate healing, lower stress response, and have other beneficial effects.

Along with being interested in fine art/museum exhibition opportunities, I’m also dreaming about creating colorful garden installations in spaces where active healing is taking place, like a cancer center, children’s hospital, wellness space, etc. - and add large scale flower gardens to support healing from the visual side.

Another thing that’s also been swimming around in my head is to put together a community stitching/mending project – and been working on notes for that. Lots on my art bucket list – but these are a few things front and center!