Interview with artist Donnie Copeland

Donnie Copeland is an abstract painter who works primarily with painted paper to produce collaged canvases emphasizing pattern, texture, and color. Originally from South Carolina, Donnie actually grew up in West Africa, where the culture, sights and sounds influence his art even today. Donnie moved back to the US and Arkadelphia, where he attended Ouachita Baptist University and earned a BA in studio art in 2000. After earning an MFA from the University of Dallas, he returned to OBU and where he is Professor of Visual Arts and Chair of the Department of Art & Design. More of Donnie’s work can be seen at Justus Fine Art Gallery in Hot Springs and at his website donniecopeland.com.

AAS: Donnie, I believe you are originally from South Carolina. So, what brought you to Arkansas and Ouachita Baptist University?

DC: The short story is that I had friends who were attending Ouachita and they had enjoyed their time there very much. My parents and I thought it was a good option. There was financial aid and I had close friends attending. But there is more to that story. At the time we were living abroad in West Africa, in Nigeria. My parents worked there as educators and my sister, brothers (who are twins) and I all graduated from high school there. Some of my very best friends growing up in Nigeria were attending Ouachita and encouraged me to look into going there. So, while it is a long way from South Carolina to Arkansas, and much, much farther from Ogbomosho, Nigeria to Arkadelphia, Arkansas - at the time, as an 18-year-old living about 6500 miles away, it didn’t seem like Arkansas and South Carolina were really that far apart or that different. Once I made the decision to come here, it changed my life. I have family in the Carolinas and visit regularly, and while I had lived and worked in North Carolina, Texas, and Missouri before returning to Arkadelphia, this place is very much home now, we have three children who would not want to move for anything.

While at Ouachita I studied art, education and communications and earned a Bachelor of Arts in Studio Art. After some time working in North Carolina and Texas, I enrolled in the graduate program at the University of Dallas, completing a Master of Fine Arts in Painting in 2005. A few years later I had the opportunity to return to Ouachita to teach on a one-year contract, which has now turned into 15 years and I have been Chair of Art & Design since 2015.

AAS: Growing up, was abstract art something that interested you?

DC: All of the places I have lived have had some connection to art and making things. And there were examples of abstraction and design all around – some of that I was more conscious of and some was certainly more in the background.

Of course, there are many creative people in my family, as there are in any family. Many on both sides worked with their hands. My grandmother was a professional seamstress, before that she worked alongside many other family members in the textile mills in the upstate of South Carolina, specifically Camperdown Mill in Greenville. Our family is still connected to what remains of the Camperdown community although the mill is long gone. My grandfather worked for many years in paint manufacturing, at Piedmont Paint Manufacturing, which I think is meaningful to my choice to work in the arts.

About abstraction, my experience in Nigeria was full of such things. Pattern and abstraction were abundant in Nigeria, in dress, textiles, architecture, and objects. The most famous art from Nigeria would be the art of the Nok, Ife and Benin cultures, but what stands out in my memory is the Hausa knot, or “endless knot”, that was common in northern parts of the country. Historically this kind of pattern was worked into the side of buildings and more commonly worked into leather goods made for tourists. In Yorubaland, the southwestern part of the country where I also lived, there was a strong hand-weaving textile tradition, and all this kind of work would revolve around decorative pattern. These are just two of many examples of how abstraction found its way into my life.

But I would not limit my use of abstraction and pattern to the purely visual and decorative. My experiences with music play a role in my thinking too. The cultures in Nigeria are very musical and in my time in Ogbomosho we attended and observed festivals and masquerades, like the Egungun festival (a festival of remembrance commemorating ancestors) and lots of Christian church services. We attended Antioch Baptist Church, where music and dance were very much integral to worship and were very lively and physically involved. I remember the music at these events, and especially the percussion, to always build up to and reach a point of a pulsing, sustained “break” of sorts, associated with dance, which I thought of as a moment of sustained emotion. I have carried these experiences along with me in my memory and I certainly relate to these memories in regard to art making, as if the paintings attempt to connect with those moments of sustained emotion.

AAS: What do you find inspires you now? What inspires you to create?

DC: As I said, all that experience of music and dance became memories after I left Nigeria. More recently and locally, I turned to ideas about land, landscape, and things like geological strata. I am referring to hillside cutaways in the Ozarks, both those cut by the rivers and others cut to make way for the highways, and how the strata are revealed in those instances. I also think of rice fields, there is a large farm just across the Ouachita River from us here in Arkadelphia that is often planted with rice. The shapes and patterns are similar. These associations became more prominent in my thinking after the first striated paintings were made and exhibited and I think they have become important as a way to communicate with audiences, as a way to connect them to the paintings in another sense. I don’t think that the striated canvases need to be associated with all these other things, but I don’t think it hurts either. Although once someone wrote that a painting of mine reminded them of a flag, which it is not. That sort of hurt because the piece was so badly misunderstood.

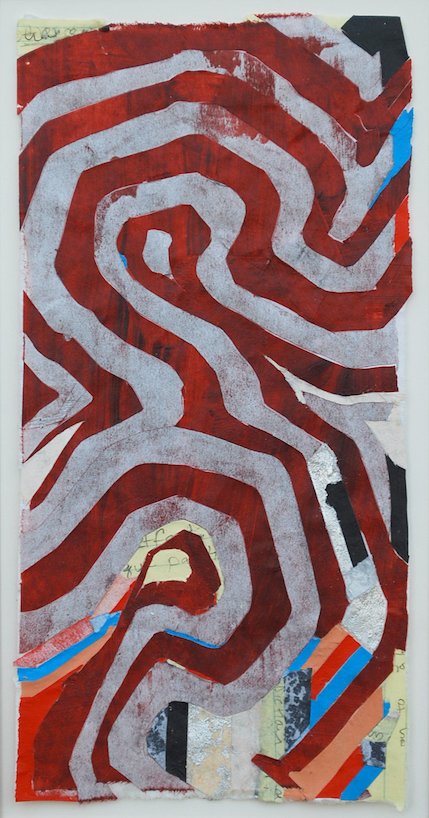

AAS: What I find so interesting about your work is that you take lines and shapes and colors that on their own can be chaotic, but somehow you make them speak to each other. STR132 is one of my favorite ‘conversations’.

STR132, acrylic, paper on paper, 19” x 17”

DC: My more recent work has taken an interest in relating bits and pieces of things that initially appear to be opposed to each other. STR132 is an example of this kind of work, of which there is an ongoing series of pieces. These efforts have involved taking scraps of previous efforts or other discarded materials that had not been considered suitable and bringing these together, finding a combination and cut pattern that would bring about a resolution between the elements. Sometimes things work out well, sometimes they return to the studio floor. I find that when the outcome is successful, I am really pleased with finding resolve in something so unlikely to have found that place of rest. And sometimes the pieces seem to work out even when they are not at rest and the discord remains. There is a pleasure in this as well.

AAS: Tell me about the techniques you use to create these paintings.

DC: One thing I really enjoy about making these paintings is the sense of adventure in producing them and to some degree, the unknown - not knowing how they will turn out. These pieces are made of painted and cut paper, all cut up and reassembled.

I typically begin work on these pieces by putting together large sheets of painted paper, full of movement, rhythm, pattern and variations in color, value, and texture. Typically, these sheets will be the size of whatever the overall size the canvas is going to be, maybe a little larger or a little smaller. Somewhere along the way, a pattern is drawn in graphite, usually on a translucent paper, which becomes a template to follow for cutting the painted sheets later on. That template pattern will be worked and reworked in consideration along with the colors, textures and other details that will be part of the arrangement. Finally, all these sheets are stacked and layered together, put on a cutting board, and then cut along the lines of the patterned template to produce what I think of as a large puzzle with long, zigzag-like pieces. There are usually 3 to 5 layers put together to be cut, and once cut, the resulting pieces offer several options, meaning different cuttings could be applied to the canvas. Selecting one cutting versus another alters the outcome, so there are many multiples of possible works that could be produced from one set of cut papers. Typically, two complete canvases will result from one initial design. Many of my pieces have a pairing, another similar piece that was made from the same effort. I think of the pair as twins.

AAS: Your work has been exhibited all around the US and the United Kingdom. Do you hear different comments from viewers in different regions of the country and abroad?

DC: It is hard to say in what different ways audiences appreciate my work, especially since I engage these audiences over time. I think I find the greatest difference in responses to my work to perhaps have something to do with the contrast between urban versus suburban versus rural audiences and the cultures that are endemic to each kind of area. I often find that urban audiences are more receptive to my work, and that is probably because they also are more often engaged in engaging with art, art is more familiar to them, and they have more exposure to it, they expect art to be just around the corner at that gallery... while that may not be the case for other audiences.

Not too long ago I was invited to show my work at an arts center just outside a small town in what is an agriculturally industrious region. I remember a couple of visitors coming into the gallery, apparently husband and wife, and she was eager to look around and encourage her husband to join in with her. He took one look around the room and then shook his head and walked out, as if to say, this is not my kind of thing, I don't care to see it. And that is fine, it was an honest response, which I appreciate on some level. Anywhere I go, the audience brings its interest, expectations, and biases with them, some expect one thing and get another. Some expect to see representational art they can read or translate, that they can understand and draw meaning from in a way they are more accustomed to, while others are willing to go with me on this visual journey and look at the works. That hasn't changed whether we are talking about Arkansas, New York, or the UK.

AAS: You have said yourself that your work is often seen as geological. I like that it can be imagined as macroscopic or microscopic views of nature. STR128 is a piece like that, to me. Tell me about that work.

STR128, acrylic, paper on canvas, 24” x 18.5”

DC: Like STR 132, STR128 is another piece in that same series, seeking to bring together several elements that had not found a place in an earlier composition. The colors were largely begun as an investigation of what if... What does this pink look like if dragged over the ochre? The question later became one of whether these pinks, ochres and purples, along with the splotchy reds and greys, could be brought together and harmonize. The result is what I think of as a series of fragments, of areas appearing more solid in contrast with the lighter, textured areas. Some of this looks like paint peeling off a wall, fragments of bits and pieces of things that used to be whole and singular.

AAS: STR112 was part of a show and installation you had in the Deep Ellum neighborhood of Dallas, at the Umbrella Gallery. I especially like the muted tones with a splash of color. Tell me about that piece and do you always work in series?

STR112, acrylic, charcoal, paper on canvas, 60” x 60”

DC: STR112 does have its twin and I suppose you could say several cousins. There is a family of pieces I produced much earlier than this that utilize the lighter grey color, a color I make by combining charcoal powder and zinc white acrylic to produce a grey that has a bit of a shimmer to it; there is nothing else like it. This is tinted even more as it goes on to the paper sheets that I would use in the final composition to give it some tonal variations between darker and lighter combinations of the charcoal and white paint. I had worked with this mixture on several canvases in prior years, on large and small canvases, sometimes pairing it with other colors of a similar tonal range but often using only the grey made with the zinc and charcoal, it is just that wonderful. Much of that work was focused on exploring variables in the undulating pattern running across the canvasses, investigating movement and negative space and how these affect the outcomes of different pieces. In STR112 I wanted to break with what had largely been an investigation of these things in monotone. So, this piece got a large helping of these various yellows, browns, solid, dark grey colors, and a bit of pink. This piece is also 5 by 5 feet, larger than most of the works I have produced.

Installation at the Umbrella Gallery in Dallas.

AAS: STR118 is a very bold piece that I find really plays with the eye. I want to sort of reach into it. Tell me about that piece and how much of the effects you achieve are preplanned or just occur as you create it.

STR118, acrylic, paper on canvas, 48” x 42”

DC: STR118 is a piece that plays with verticality and visual weight. There is a tension that has developed between the top versus the busy, lower portion of the work. The color is also significant, it is all one color of paint which has a lot of transparency to it, so there is a visual play between layers of paint, where some areas are thin and transparent, and others are more densely painted and opaque. Making the piece started from the focal area, situated in the lower third of the canvas, working out from there and building throughout the rest of the canvas. That design and focal point was preplanned, but the decision to leave parts of the top of the piece open and bare, to create a visual weight and balance with the lower portion of the work, came about during the making of the piece.

AAS: Who are some of the artists who you admire and have drawn inspiration from?

DC: As a student I was working hard at representational modes of art making, but I was absolutely fascinated with Sammy Peters’ paintings and the depth of his surfaces. I saw these on display on gallery walks in Hot Springs. There are whole worlds within his paintings. Others have played a role too. I remember seeing a show of Stephen Wise’s paintings and feeling very liberated by what he was doing at the time, feeling like he was giving me permission to pursue something that would be hard to name, something that would not be easily consumed or understood.

In addition to the artists and cultures I have already mentioned, I would add El Anatsui. I believe you saw his work in Amsterdam and posted a few images of his work on the blog. I do admire his work and the ideas he puts out there. The work itself is just visually stunning. I would have liked to have met him when I lived in Nigeria, he had a studio not far away from where we lived, but I was unaware of him then, only learning about him years later in museums in the United States. I also dearly love the work of Vik Muniz, who I did get to meet in person once at a debut of his film, Wasteland, in New York City. I think many of us first got to know him by watching Egg the Art Show, a great show that I miss. As a student of painting, I of course loved baroque painting, and still do, especially Dutch still lifes - vanitas and otherwise. I have always associated Ecclesiastes 6:7 with those pieces, which reads something like, "All our efforts are for our mouths, but our souls are never satisfied". I was also engrossed in surrealism as a student, not just that of the 1930s, but in more contemporary surrealism, such as in the work of Polish poster illustrators like Wiesław Wałkuski and Wiktor Sadowski at work in the 1980s and 1990s. I am also indebted to the concept of faktura, which I take as the appreciation of a work for the material and physical attributions present in the work, rather than its symbolic and metaphorical attributes, which are not present. And as Carey Roberson reminds me, as an abstract painter, I am first indebted to Hilma af Klint. I look forward to catching her work in an exhibit sometime. But these are not the only artists I think of, I have to go back to all those unknown and unnamed artists, those bronze casters in Benin, makers of the gothic, and all those persons who would have set the little tesserae fifty feet above the floor in all manner of churches. I am indebted to and inspired by all these.

AAS: Tell me about the OBU art program. Are students apprehensive about their future as artists and do you think the next generation of artists will be any different given how easy it is – almost unavoidable–to see all kinds of art all the time?

DC: At Ouachita we look to help young artists grow in four key areas: developing studio skills and knowledge, developing historical knowledge, encouraging their own personal creativity and vision, and communication with their audience. About students, I think that there’s always some apprehension among students who are seriously considering a future in the arts. However, I think that those students who are serious about art have a deep sense of commitment and a kind of faith that art is meaningful and needed and that there will be an audience for it. I often encourage students to read Makoto Fujimura's Culture Care, which discuss these matters. I also think a little bit of fear is good for everyone. We are a relatively small art program, in a liberal arts context, meaning students learn broadly across many disciplines along with their studies in art and design. We offer degrees in art education, studio art, and graphic design. I am grateful to work alongside some excellent people including Carey Roberson, who you interviewed recently, and René Zimny and Ferris Williams. We also have ceramic artist Logan Hunter, and Candace Eriksson is teaching in our art education area. We are part of a much bigger program that includes music and theatre. Any given week, you can typically visit multiple performances and exhibits. I am also grateful that we have recently benefited from the generous support of one of our own, Rosemary Gossett Adams, an art major at Ouachita some years ago, who has helped us to improve our classrooms and especially our galleries.