Interview with artist David Mudrinich

David Mudrinich recently retired from the Department of Art at Arkansas Tech University in Russellville., where he was a professor of drawing and painting. David is a location painter recognized for his expansive landscapes and more intimate locations. His works are part of major private and corporate collections around Arkansas and throughout the South. More of David’s work can be seen at Cantrell Gallery in Little Rock, Arkansas.

AAS: David, you just retired from Arkansas Tech University after teaching art for more than 20 years there. What brought you to ATU?

DM: Art jobs in higher education are very competitive and hard to get. If you want to secure one, you have to be willing to move for that opportunity. ATU was one of the schools that I applied to and I was fortunate enough to gain an interview. The meeting went well and I received a job offer at the end of my visit. I called home that night and my wife Eve agreed we should make a go of it.

The area reminded me a bit of western Pennsylvania where I was born. I attended Penn State University initially enrolling to be a naturalist in parks and recreation. I found myself hanging out with art students more than science people, so after a year my longstanding interest in art motivated me to switch my major to art education. My desire to teach at the college level eventually led me to completing my MFA degree in drawing and painting at the University of Georgia.

AAS: When did your passion for art begin and when did you realize you wanted to teach?

DM: As far back as I remember, I was always drawing. As a kid I would sit at the kitchen table in the evening and draw animals. I would then cut them out and staple them onto another drawing that I did of a landscape. It must have been a desire to enhance some sort of 3-D effect.

In elementary school, we had art twice a month with a roaming art teacher. She was the first art professional I met. When I got into high school the guidance counselors said I should take additional math courses, instead of art, to increase my chances of getting into college. I finally got into art class my junior and senior year. My teacher, Charles Mangus, had a unique character and provided the space that allowed me to begin to consider art as a career option. Art really wasn’t encouraged by either the community or my family as a way to make a living though. That is why I hesitated to major in art and first looked at a career option that would have me outdoors.

When I switched majors, I found out that the art education program at Penn State was top notch in the country at that time. The passion of the instructors and their ability to show the relationship that the arts played in culture and the world was highly motivating. As I searched for my purpose in life, teaching art seemed to be a logical way to share and communicate with others.

“If your art has a good sense of design and a visual message that reflects on humanity, you can build a bridge that will reach out to others.”

AAS: Would you talk more about your love of the outdoors and what drives you to want to capture the landscapes you are known for?

DM: I was always outside as a kid growing up. We lived on a small plot of land with a creek running through the back. This is where I first discovered the natural world of plants, animals and design patterns in nature. The creek was always moving, supporting life and changing the natural appearance of the stream bank.

Parallel to this experience, I would also spend time in the steel mill town of Farrell, Pennsylvania where I was born and where my grandmothers still lived. It was just over the hill, three miles from this backyard creek, but it was an extremely different environment. All the houses and streets were in rows lining the hillside. This setting was dwarfed by the gigantic, loud, dark, bellowing steel mills that filled the river valley below. The blast furnaces would turn the sky red at night. I always thought that the brick buildings were black in town until I saw them pressure-washed one time, revealing their true red-brown color. This dual contrast in environments, as a youth, was striking and remains with me forever.

As this steel economy collapsed, I moved south near Athens, Georgia. Here my young family and I lived mostly off-grid, renting an old tenant farmhouse without plumbing and heating only with wood that was cut from the land. Living like this brought you close to all the elements of nature. It was a large piece of acreage that backed up close to the University of Georgia School of Forest Resources research property called Whitehall Forest. To help support my family I was hired in that experimental forest as a forestry technician, working a number of years while I also attended graduate school at UGA for art. This experience provided a practical scientific understanding of the environment that I blended with my more poetic spiritual view on nature. These accumulating experiences gave me more insight into the landscape that I seek to portray.

Red Rock Valley, pastel on dark grey paper, 10” x 15”

AAS: One of my favorite pieces is Red Rock Valley. It is a pastel done on grey paper. Many of your pastel landscapes are on dark paper. Why is that?

DM: That piece is from a region in the Ozarks in Newton County. I tend to get a sense of visual euphoria when looking out through distant space. That location moved me. The tree lines and hills become irregular patterns of shapes and colors. There is also a time element that I become aware of in a landscape like this. It represents both the historic time of what came before and the present moment I am currently witnessing. I try to have the finished composition I create reflect a mood of both movement and rest, as well as present time and eternity.

When painting or working in pastel I rarely work on a white surface. I’ll tint the canvas a neutral dark warm color or use colored paper when working in pastel. The dark paper used in Red Rock Valley establishes the darkest color I use in the drawing. This is the opposite approach of using the white of a paper for highlights. I then add lighter values and colors, working towards the final application of highlights to get my desired contrast. Starting out with the darks makes me feel like I am working with the deeper soul of the subject matter. Technically it allows me to work faster too.

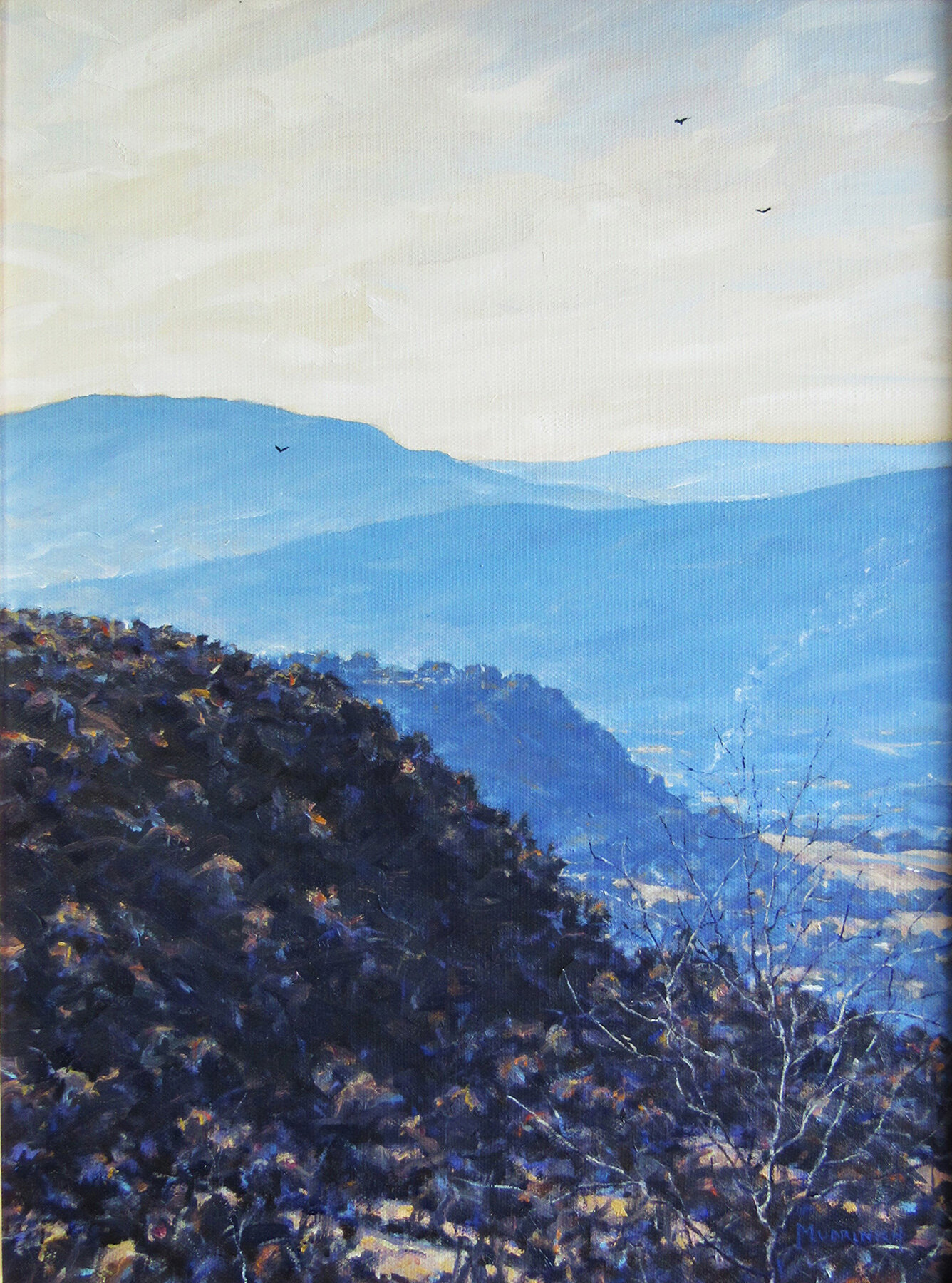

Passage, oil on canvas, 30” x 24”

AAS: You also paint in oil and I have to say Passage just took my breath away the first time I saw it. I found its imagery haunting. Would you talk about that painting?

DM: That work is inspired by a view from, ironically, Crow Mountain. It is a hill that runs parallel along Interstate 40 between Atkins and Russellville. Often, I will observe crows lifting up from the valley, so I decided to intersect their flight pattern over the interstate. There is a time element intended in the piece that reflects a journey. It could be traveling to a particular destination or referencing your journey through life. The aerial perspective of the crows in flight suggests a more spiritual sense of time, even though this is a specific place.

AAS: When you decide to paint a landscape, what elements of the vista or elements in the foreground do feel are most important to the painting?

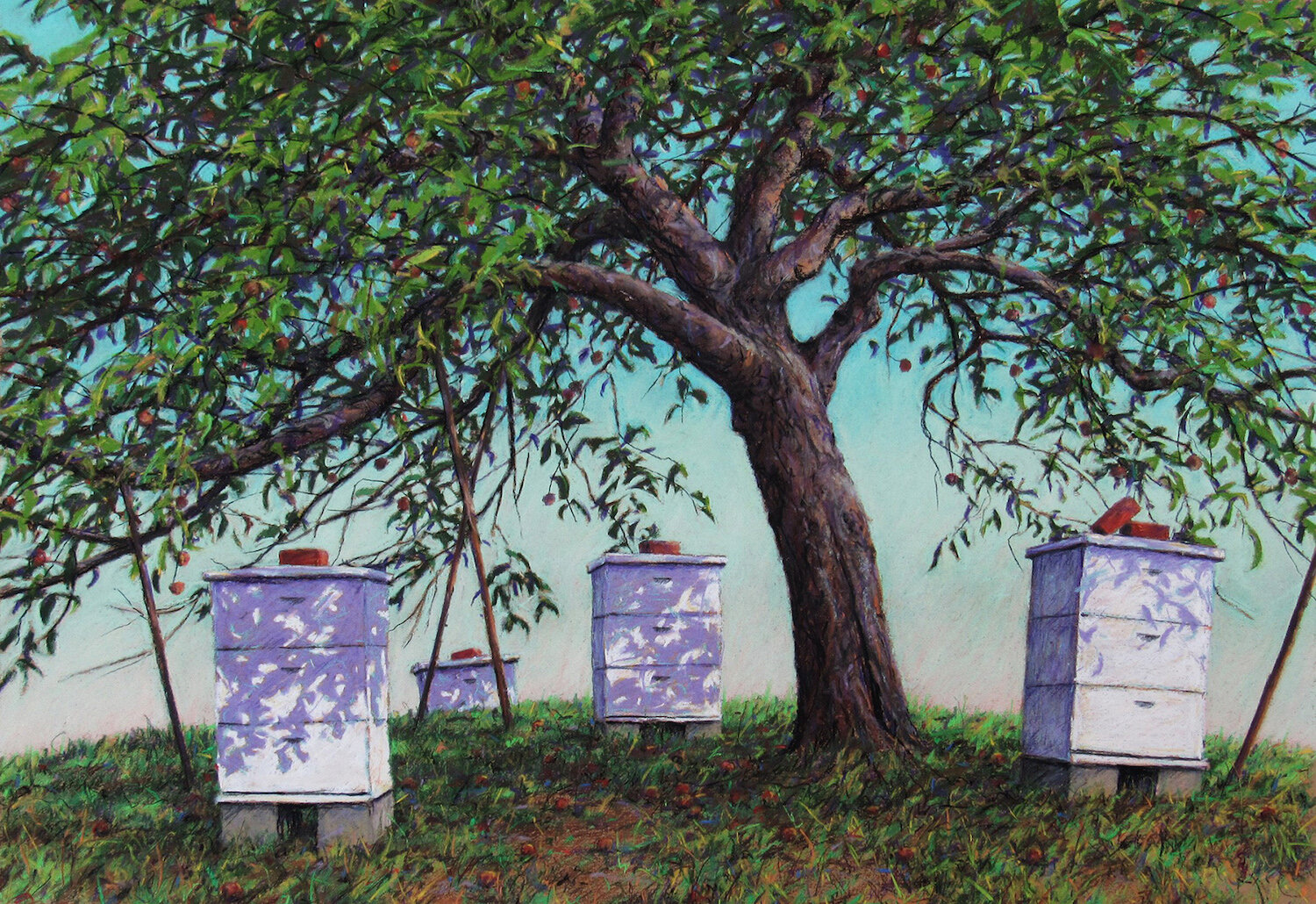

DM: It really depends on the particular experience I have with a place. As I mentioned before, I enjoy the patterns revealed in a vista that occupies deep space. By emphasizing particular shapes and colors I try to guide the viewer’s eye through the composition. Sometimes I will often avoid traditional composition conventions and eliminate any foreground material to create a feeling of suspension within that distant space. Other times, like with the beehive series, I will rely on the character nature of the subject matter and place it in the foreground to help define the narrative of the piece. Some compositions are invented and are based on several different places that I have experienced over time. I may include foreground, middle ground and background to satisfy my design or narrative intent with a work.

Robins, pastel on brown paper, 26” x 18”

AAS: You and I both seem to share a fascination with bees and beehives. I grew up in south Louisiana and there were many beehives in fields along the country roads.

DM: They really are intriguing structures, aren’t they? My neighbors have an apiary that I see every day. I got attracted to the visual rhythms of the hives as they are arranged within this landscape. I began doing drawings of the boxes from my yard.

In researching the subject, I found that bees and hives have been symbolic since ancient times and in many cultures. In ancient Egypt, bees were considered to represent the tears of the sun-god RA. Because of their sudden reappearance after being dormant, they became symbols of death and rebirth. In early Christianity too, they tended to symbolize the coming of spring and the religious idea of the Resurrection.

Many of the apiaries I now come across are at abandoned locations that were once a home, farm or business. The introduction of these hives seems to symbolize a regeneration of purpose to what was once an active place. The visual character of the individual hives and the variety of locations that I find them in is what motivated me to begin creating this series.

Discordant Hives, pastel on brown paper, 26” x 18”

AAS: I guess one of your most recognizable hive paintings is Discordant Hives, which was in the 2020 Annual Delta Exhibition. It is an extraordinary work with great composition. Would you talk about that piece?

DM: Discordant Hives is based on an apiary next to an old house that I came upon in Carden Bottom along the Arkansas River. The house was long abandoned, overgrown and had succumbed to the elements of time. Next to it was a complex of over a dozen beehives buzzing and bustling with activity. I liked the visual contrast of the two different structures next to each other. None of the hive boxes were color coordinated which gave the site a random funky feel. The setting seemed to fit that regeneration of purpose I talked about earlier, which gave the locale a unique sense of place. I was pleased to have it selected for the Delta Exhibition. It sparked some curiosity with many viewers.

AAS: You paint in pastels and oil. Do you have a preference depending on the subject you want to paint or is it just your mood at the moment?

DM: You know, it must be mostly the mood of the moment. I tend to get bored working in just one medium and often switch after completing about three works. I also work in acrylic, watercolor and a variety of drawing media to get what I am after.

For most compositions, I usually do a drawing or color study on location that gives me a wider experience of the sounds, smells, wind, temperature, texture and history that adds to the definition of the place. Those studies may be done in charcoal, crayon watercolor or acrylic. I will rely on these sketches and occasional photographs to create a larger more finished piece in the studio. Sometimes the entire work is completed on-site as in the night view of Along the Illinois Bayou. Other times it might be a composition reconstruction from my memory that dominates the layout.

My studio isn’t that well heated, so I tend to draw more with pastel in the winter. The drawing action is faster and more direct than mixing paint. This keeps me moving to generate heat when the temperature is down. I tend to paint more in oil during the warmer months.

Along the Illinois Bayou, oil pastel on dark grey paper, 7” x 20”

AAS: You have taught art at the college level for so many years. Students can have very fragile egos, so how have you learned over the years to give constructive criticism to students without discouraging them?

DM: When a student is working on an individual project, I start by asking them questions. Why did you choose this subject? What does this content or design mean to you? What is your focus or intent for the viewer? Once I understand what they are attempting to do, I can offer suggestions that help them better to achieve their own goals. Maybe they need to increase the size of their focal point and move it to the foreground. Maybe they need to remove space and shapes that compete with the subject that they are trying to stress…that sort of thing. If we center the discussion on their ideas, there always is a better outcome. There is a mutual trust that has to be built between us for that to work.

Then there is the question of what do you want to do with your art and who is your audience? Once you decide that, if you really want to make art a major part of your life you need to develop the discipline to stay active; be flexible in pursuing opportunities; research and network your areas of interest; tolerate rejection and enjoy what you are doing. Most artists I know do additional tasks to help them make a living. Some are counselors, psychologists, carpenters and real estate agents. Like many others, I teach to help me survive.

There is so little that we can control in this life. Your art is one thing that you can control and use to communicate what is really important to you. If your art has a good sense of design and a visual message that reflects on humanity, you can build a bridge that will reach out to others.