Interview with artist/art instructor Robert Bean

Robert Bean is a native Arkansan who grew up in North Little Rock. He earned a degree in studio art with emphasis in drawing from the University of Arkansas Little Rock. He is an artist and teacher – now heading the Department of Painting and Drawing at the Museum School of the Arkansas Arts Center. Robert’s work can be found at Gallery 26, his website, and on his Instagram. His photo is courtesy of the Arkansas Arts Center.

AAS: You describe yourself as a storyteller and you mention in your bio that comic books were a big influence as a child. What are your strongest memories about comic books growing up? How did comic books shape your interest in story telling?

“Comics are my foundation, even if that’s not the format I use to express my ideas, my narratives, and my images.”

RB: When I was about eight I can remember going to the Little Rock airport with my parents. I don’t remember why we were there, who we were picking up or meeting, but I do remember that we got there early. We had time to kill, and so we went to the little newsstand and started looking around. My parents, wanting to help keep me occupied, gave in and bought me a couple of comic books. I believe they were issues of the Avengers. I sat down to read them and was entranced. It didn’t matter that I had managed to pick up a couple of issues that were completing a story arc I hadn’t read the first parts of. I was hooked. I had read comics before, and I had drawn before, but never had those two things clicked for me. They were dynamic. They had an explosion of energy I hadn’t ever experienced before. More to the point – I could see the drawing in them. I could see the marks. It was illuminating – and they told a story – with drawing – with words.

After that I started reading comics more regularly. I became a collector, and an imitator. I started copying the drawings I was seeing in comics and that’s where I really started to learn for the first time. I started trying to make my own comics.

All of these things have stayed as strong influences on me and my work. I’m still far more interested in the draftsmanship you’ll see in illustration or good drawing than I am in the contemporary works you’ll often see at some of the bigger fine art events around the world. I’d rather dig through, and be influenced by, a book on the illustrations of pulp fiction magazine covers from decades ago than read an issue of Art Forum. It doesn’t mean I don’t understand, appreciate and like some of the things I come across in Art Forum, but rather that the kind of work I’m exposed to there doesn’t sing to me the way an incredibly complex and well rendered noir illustration will.

I work almost exclusively in series, and I attribute that to my upbringing on comics. I used to try and create one off style paintings, but inevitably they just didn’t have the same power to me as creating twenty paintings all exploring the same theme and using a lot of similar elements. Eventually, I even just started to relate all the images together, allowing them to almost be read like a story. Comics are my foundation, even if that’s not the format I use to express my ideas, my narratives, and my images.

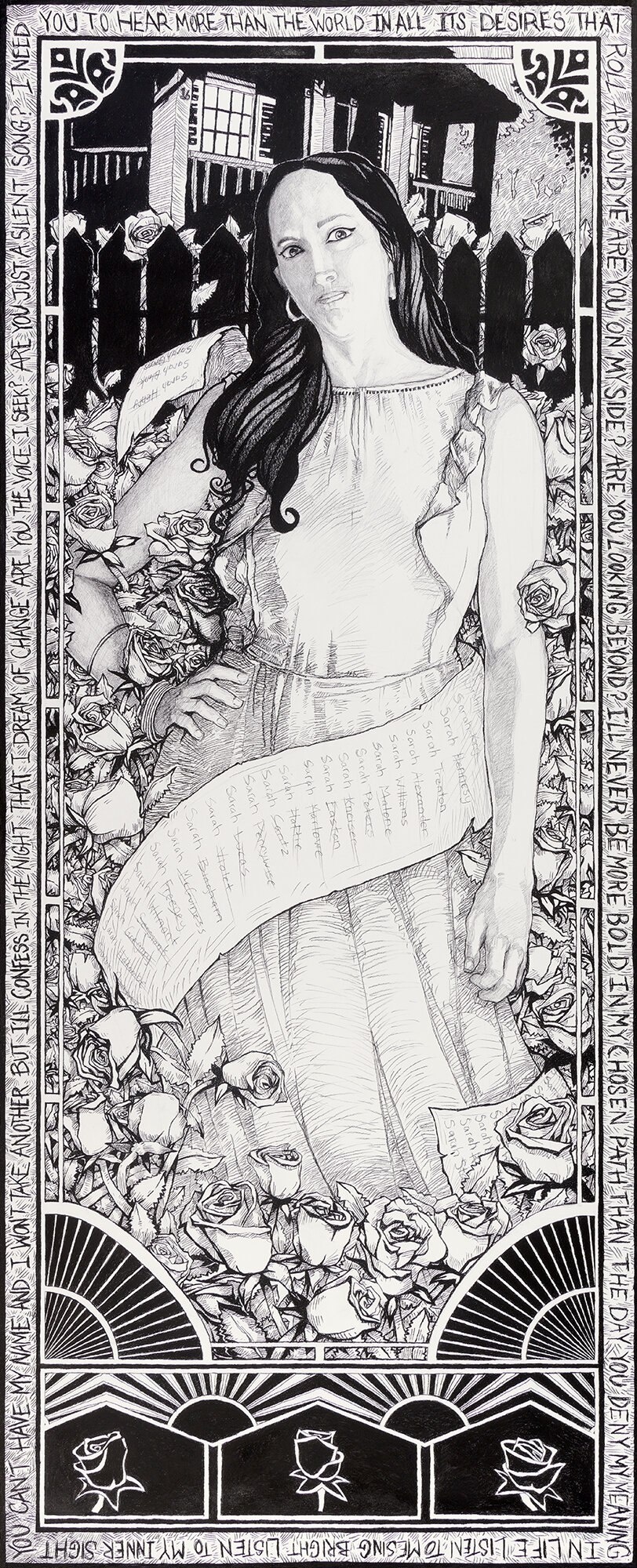

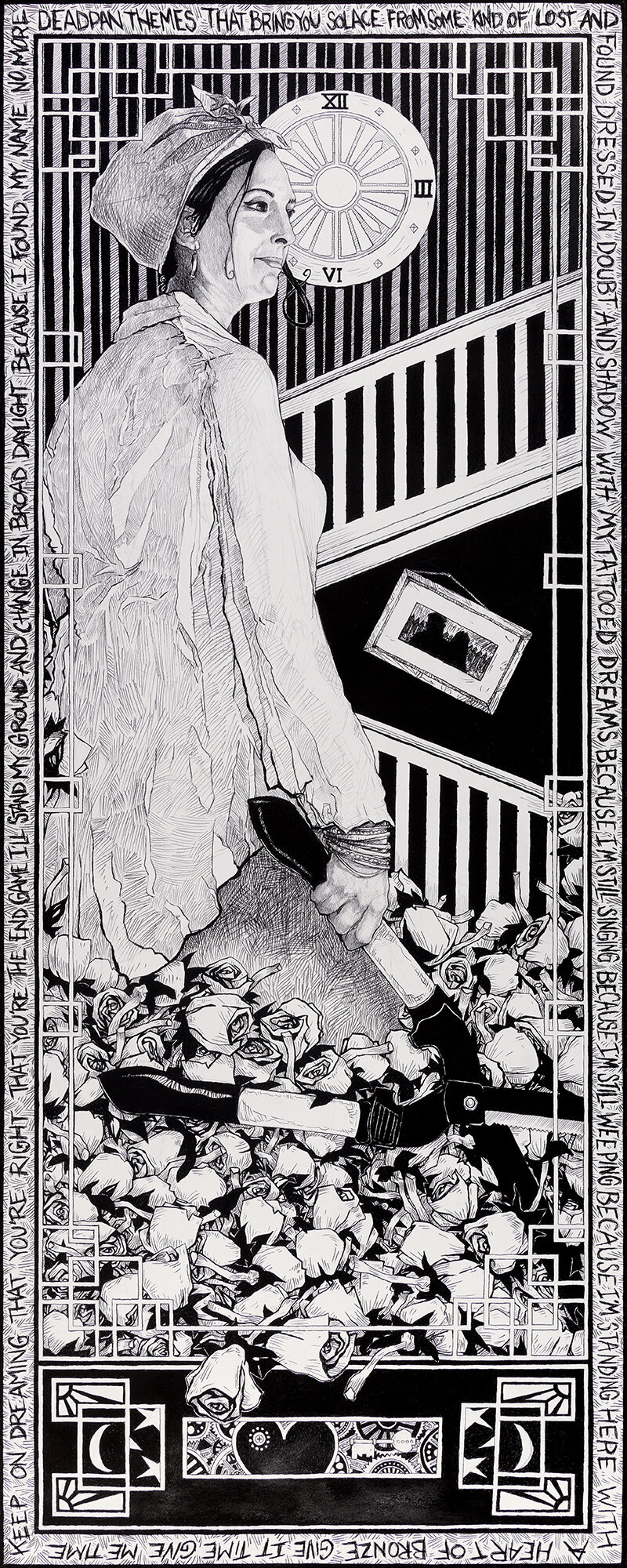

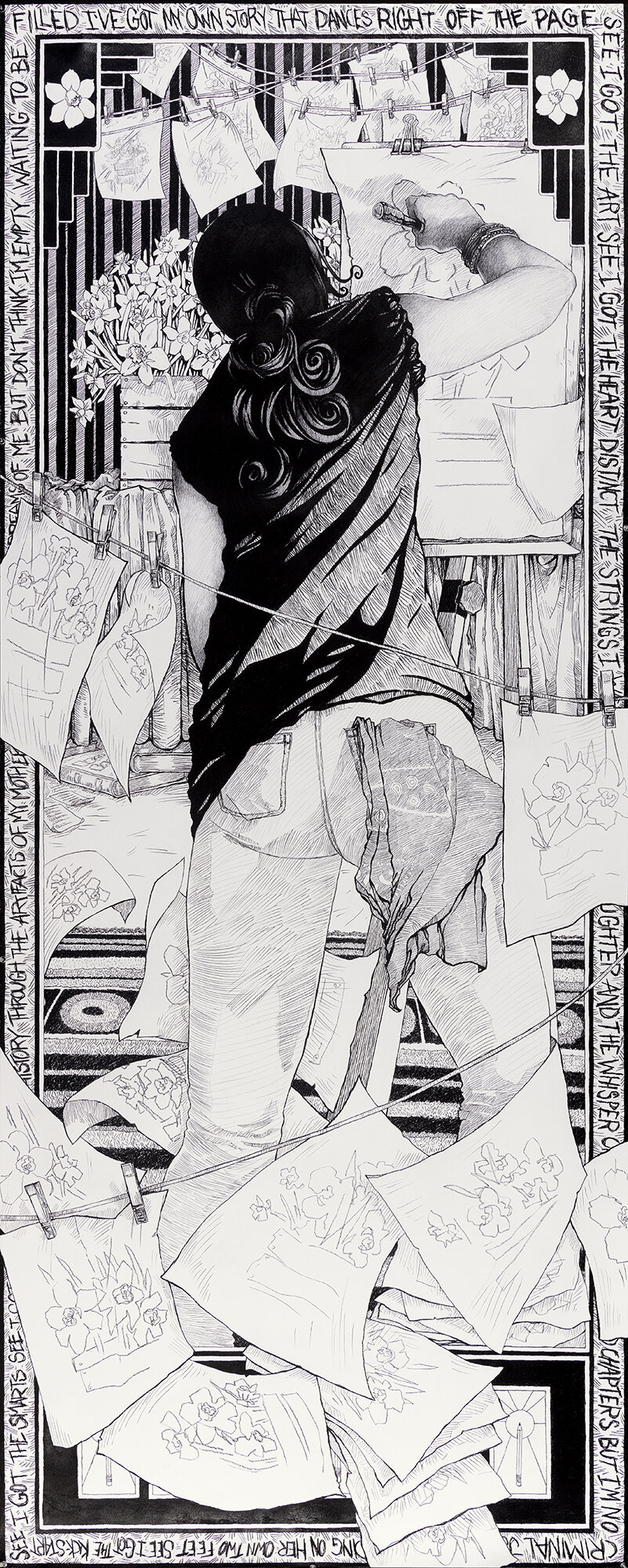

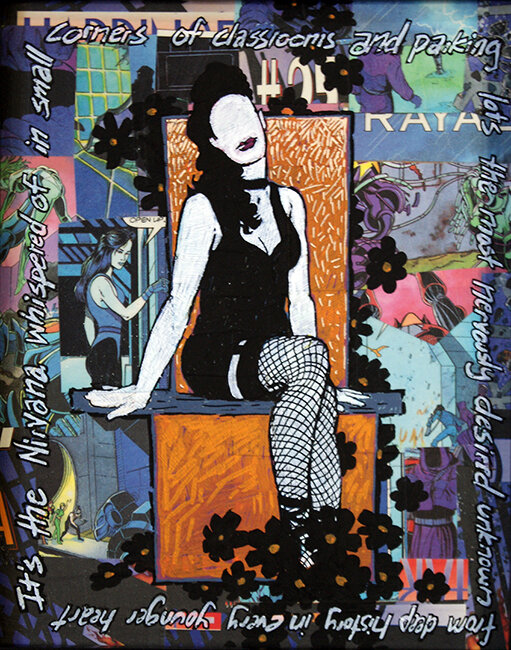

Pulp fictions Pulp Truths, ink on paper, 17” x 11”

AAS: I can see the influence of comic book illustration in your wonderful Collage Narrative Series from 2019. What inspires you to draw these days? Will there be a new 2020 series reflecting the social changes we are all going through?

RB: That series actually uses parts of comics to create the collage background I drew on. As a collector, it was soul wrenching to cut up comics, even if those comics weren’t valuable and I had multiple copies of each issue. But it was also freeing in a way to put those bits and pieces of comic pages together into something new, something I could build on. I had a lot of fun, once I got over the deep gasps of “can I really do this?” while cutting them up.

I’m inspired by a lot of things, but rarely the “big” topics of the day. I’m always more fascinated by the individual, the character, the story of the person and how they react to a setting or a conflict. So even if there’s something grand in scale, I’d rather tell a story about the aches, pains, triumphs and joys of a single person or couple of people within that drama then try to comment in broad strokes about a big concept. To me you can express so much more about that big event or big idea through the very human frailties, failures, and reactions of a single person. To use a current example, I’m not interested in making works that are blatantly about a pandemic, but I would be very interested in exploring how a single person is dealing with being isolated at home alone (and the reason behind it could be a pandemic or something else, it’s not the cause I’m interested in, but rather the effect).

I know that what’s going on in the world will influence my work – you can’t really escape it. But, I have a feeling it will be reflected in the expression of something on a much smaller stage rather than something on a societal level.

AAS: An illustrator is someone who enhances or interprets written material with visuals? What does illustration mean to you as an artist [who creates both the ‘written concept’ and visuals]?

“So even if there’s something grand in scale, I’d rather tell a story about the aches, pains, triumphs and joys of a single person or couple of people within that drama then try to comment in broad strokes about a big concept.”

RB: I think the term illustrator is a tricky one, and one that often sits the artist labeled with it at the kids table when you’re having the GREAT BIG WIDE WORLD OF ART WITH A CAPITAL A dinner party. It’s as if that very act of trying to interpret a concept or written content somehow lessens the work. I think that’s crap. There’s this weird outlook on artists that some people have that the artist is this kind of truthsayer, this seer, about what is really going on in the world. That true art, good art, rises from within the artist, this mystical place of x-ray vision that let’s them see the world as it truly is and from which they will express all the great things in life. That they cannot explore something unless they have lived it and are expressing it from their own experience. It’s that adage of “write what you know”. Well, what most of us know would make for a lot of pretty boring art, and boring stories. We don’t all live highly dramatic ready for the silver screen kind of lives, but we do have questioning minds that lead us to explore ideas. To me it’s that tension, that exploration, that makes really good art. That’s also, in many ways, what to me an illustrator is – an explorer of ideas that attempts to envision and express that very exploration. It may not be an inner truth, one of the world’s great ideas, but it’s an honest attempt at understanding and creating.

AAS: When did you become Department Chair of Painting and Drawing at the Arkansas Arts Center Museum School?

RB: About five years ago Emily Wood, who was the Department Chair at the time, asked me if I would be willing to step in and cover a drawing class that had a few weeks left and the instructor needed to move on to a new job out of town. I was happy to do so, and really enjoyed working at the Museum School. Emily asked me to teach a few more classes and I did. When Emily needed to step away from being the Chair of those two departments, I was asked to step into the role and readily agreed.

It's an incredible place to work and teach (I have an incredible group of coworkers that have a devotion and love of the arts) and has one of the best groups of students you’ll ever find. Everyone who is there wants to be there, they have a hunger and desire to learn how to draw and paint, to pull prints, to make things with clay or learn woodworking or making things with glass. It’s a genuine, deep desire to learn and understand. It’s an amazing thing to be around. They aren’t doing it for a grade, they are doing it because it’s what they want to know how to do, and they work at it, really work at it to improve and grow as artists. We’re in the middle of a big rebuilding project for our MacArthur Park location, so for right now we’re working out of a temporary space (which is wonderful in its own right), but one of the other great things about teaching for the Museum School is that when the galleries are open at the Arkansas Arts Center, I can teach from the galleries.

How cool is it to talk about drawing then take the class into the galleries and show them actual drawings by some of the greatest artistic minds in history? That’s something you just can’t get everywhere. It’s an absolute joy to teach with that kind of resource.

It’s also a way for me to give back to an institution that helped me as a young artist – I took classes from the Museum School when I was young. My first figure drawing class was at the Museum School. I cannot express how meaningful it was to have that experience, and I’m happy to be able to carry on the tradition of helping others get that very same experience that I had as a young artist.

“Enjoy the positives and praises, roll with the blow of those that are negative or don’t care, and keep your eye on the next piece on the easel, because that’s the important part, that’s the thing you have to remember: you get to do one of the coolest things in life and make art and the next piece is waiting for you.”

AAS: Years ago, I took a watercolor and then two pottery classes at the AAC Museum School. I was not very good, but the instructors never ever were discouraging. I think the Museum School is an important component of the AAC for the young and ‘old’. What is the overarching goal of your department.

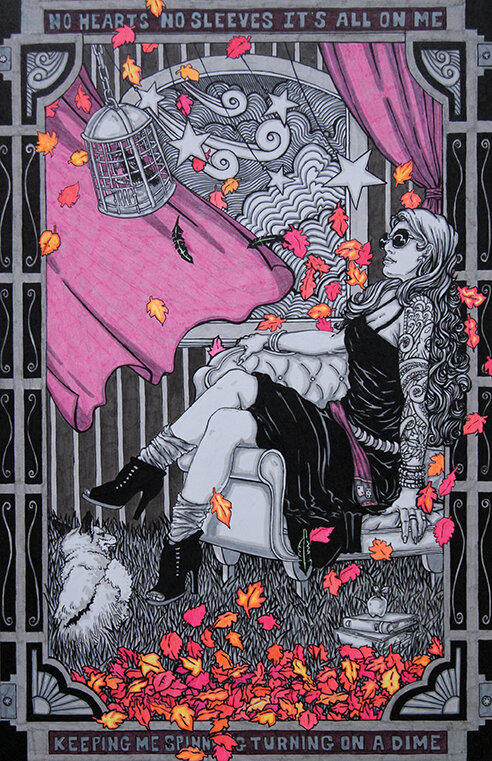

#drawmeathome Day 15 - Ume, Mars Lumograph, white charcoal and colored pencils on toned gray paper, 12” x 9”

RB: The Museum School is a gem for Arkansas. An absolute gem. We have a group of faculty that love not only their craft but their students and will work as hard as they can to help those students develop as artists. You’re absolutely right about how positive our instructors are.

And you’re right about age groups – we have classes for almost every age group. I’ve had students in my classes that were teenagers up to students who were looking at eight or nine decades of being around. All of them were happy to be there and learn, too.

As for my departments, I’ve been working to build a curriculum that focuses on learning the fundamentals, the skills and technical knowledge of a medium before you start to really explore putting a lot of meaning and high concepts. We have classes that do all of those things, but we want you to be comfortable knowing how to draw before you decide what it is that you’re going to draw, if that makes sense. For those that have a good grasp of the fundamental skills, or once they’ve learned them in the Museum School, we offer classes that allow them to explore expressing who they are as artists, or present an interesting technical approach to working in drawing and painting. For example, once you have the basics down of drawing, I teach a class that meets off-site called Urban Sketchbook, where we go to different places around Little Rock and North Little Rock and learn how to draw what is happening around us. It’s high energy and helps if you have a basic understanding of drawing techniques. So you take Beginning Drawing and learn those fundamentals, then take Urban Sketchbook and see a different side of drawing, one that isn’t in the studio. We want you to be technically proficient AND expressive, not one or the other.

#drawmeathome Day 11 - Ume, Mars Lumograph, white charcoal and colored pencils on toned gray paper, 9” x 12”

AAS: Has the desire to teach drawing always been there? You have somewhat come full circle from student at UALR to teacher at the AAC Museum School. What advice do you give to young (or not so young) budding artists who might be afraid to show their art to the public.

RB: I come from a family of teachers. My grandparents were teachers for a long time, my aunt and uncle were teachers, and I’ve kind of been around it all of my life. Early on in my career I didn’t want to teach. It wasn’t because I didn’t enjoy the thought of it, it’s because just trying to learn how to be an artist is hard enough. I didn’t want to try and learn to be a teacher at the same time.

I’m actually adjunct instructor at the University of Arkansas Little Rock right now as well. They asked me to come teach figure drawing, which I’m doing and enjoying. It’s a different environment than the Museum School – there’s a little more pressure I think on the students because they are dealing with grades and a GPA – but it’s still a great place to be. It’s also interesting to be teaching alongside some of the professors I had when I was an undergrad. There are a lot of great people at the Windgate Center for Art and Design. I think the art department is a terrific program that is only getting better.

As for that last part, the advice for budding artists who might be afraid to show their art to the public, all I can say is this: Don’t be. Not everyone will love your work. That’s ok. That’s part of it. You can take some of the greatest artists there have ever been, hang their work on the walls, and still have people that zone out when looking at it. Art is subjective, it has to connect with the viewer, and sometimes there just aren’t connections to be made. If you’re worried that your work isn’t good enough, stop doing that too. You’re the artist and I’m going to go ahead and tell you now, you’ll mostly think it isn’t up to par. You’ll have occasional works that you think I nailed it! But more often than not, there will be an aspect of your work that you aren’t happy with. That’s ok, that’s what’s supposed to happen, it’s what will motivate you and help push you forward to make the next piece. Put what you make out there, and let others make their own decision about your work. Enjoy the positives and praises, roll with the blow of those that are negative or don’t care, and keep your eye on the next piece on the easel, because that’s the important part, that’s the thing you have to remember: you get to do one of the coolest things in life and make art and the next piece is waiting for you. So, get your work out there, let others enjoy it, and while they’re enjoying it go make something else to show.