Interview with artist Andy Huss

Andy Huss is a Little Rock sculptor and educator. After earning degrees in sculpture from Northern Michigan University and the University of Michigan, he studied sculpture with some of the most influential sculptors in the country before relocated to Arkansas. Andy has taught at several central Arkansas Universities and is currently an Assistant Professor of Art at Hendrix College. More of his work can be found at Boswell Mourot Fine Art in Little Rock, and at his Instagram and website husssculpture.com.

AAS: Andy, where are you from originally.

AH: I grew up in northern Michigan. I graduated from Northern Michigan University in 1988 with a BFA in Sculpture, then graduated from the University of Michigan a few years later with an MFA in Sculpture. I then studied with a sculptor named Bob Engman at the University of Pennsylvania for a year. About 5 years ago I decided to finally put my degrees to work for me and got work teaching art as an adjunct at University of Central Arkansas, Arkansas Tech University and Hendrix College. Ultimately Hendrix College hired me as a full-time Assistant Professor of art teaching sculpture and ceramics a couple of years ago.

AAS: Did you always like working with your hands and building things as a kid?

AH: Mostly just the usual kid stuff. Go-carts, tree forts, plastic models of cars, Estes rockets. In grade school there was a poster contest sponsored by the local bank. I hadn’t finished my entry and was quite disappointed when I found it had been submitted anyway. I was given a C or a D or something. Turned out my unfinished poster won the contest and my teacher actually apologized and changed my grade to an A. I felt bad for her because at that moment I knew I only won because my dad was buddies with everyone at the bank. He was an elected official, and everyone was always trading favors. I certainly didn’t deserve to win the poster contest. I won because the fix was in. I learned a lot about the nature of the way the world works because of that experience, and I’ve looked at the system with a jaded eye since then. I’ve carried that lesson with me all these years since.

It wasn’t until undergrad when I discovered a love for creating objects and probing the history of art, I became dedicated to the lifestyle. When I switched my major to art, there were resources and encouragement that had been previously unavailable. That’s the environment I expose my students to, a place where they can explore ideas and materials with lots of encouragement and no judgement.

“I’ve always been intrigued with the three-dimensional form. To me, the negative space that envelops a piece is as important as the piece itself, and that is the way I approach my work.”

AAS: Your sculptures place emphasis more on the openness or what’s not there rather than the heaviness that is often depicted in sculpture. Why is that?

AH: I’ve always been intrigued with the three-dimensional form. To me, the negative space that envelops a piece is as important as the piece itself, and that is the way I approach my work. Sculptors like Brancusi and Hepworth developed work that defied traditional expectations, they were intuitively considering the positive and negative space as part of the whole.

AAS: One of my favorite examples of that airiness is an almost spiral form in aluminum. Tell me about that piece.

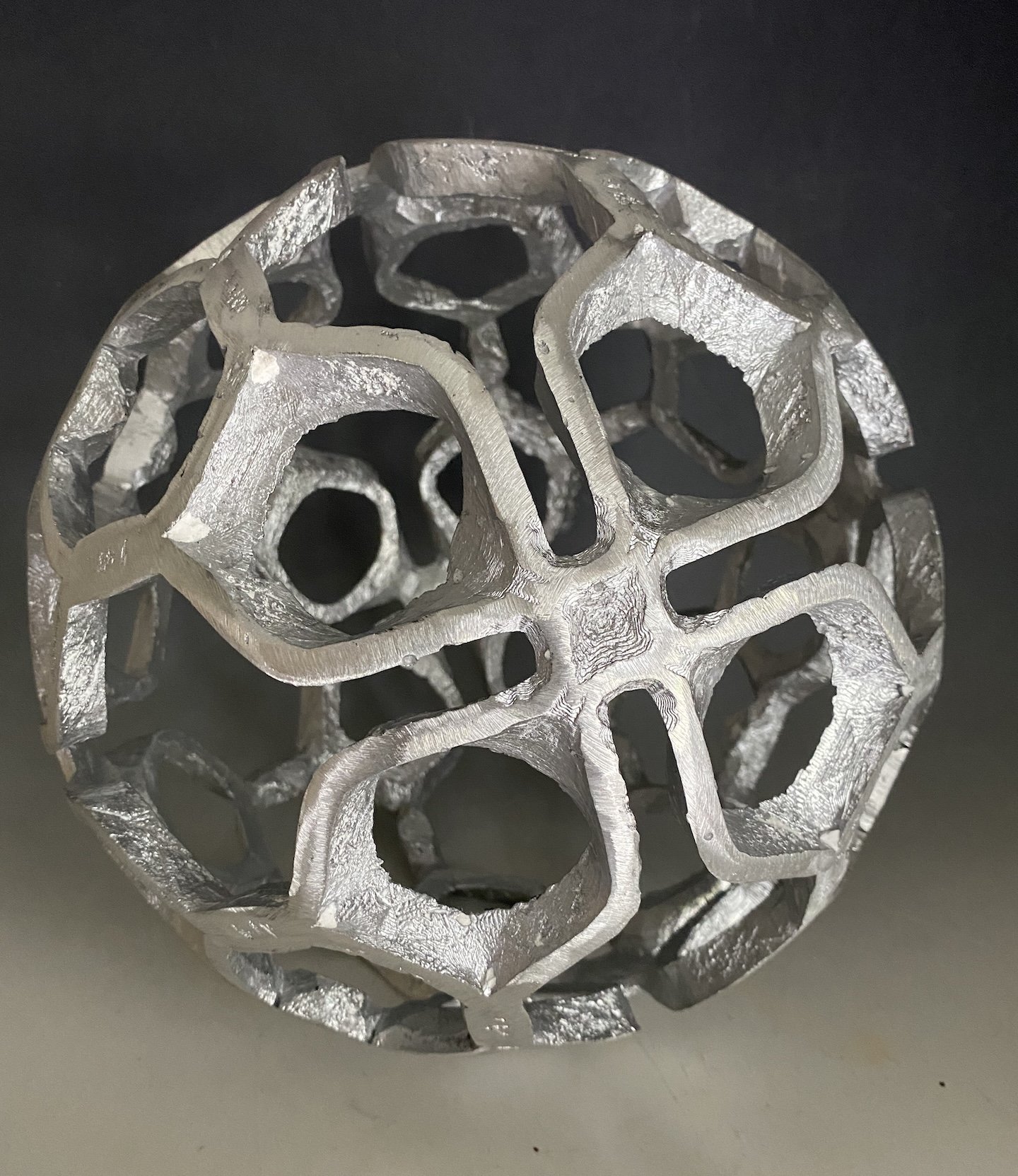

AH: That piece was as much an exploration of form as an exercise in what was possible to create with the 3D printer. The form is based on an equation that describes a triply periodic minimal surface called a gyroid. It is a complex form that can be reduced to a single unit cell. That cell is based on a cube and can be assembled into an infinite three-dimensional grid. All I did was remove an ovoid shaped piece from that infinite grid. It’s very difficult to visualize a gyroid. This was just one in a series of pieces I’ve messed around with while trying to understand the nature of this weird object. I’ve since seen people do similar things. I guess it’s what you do when you first start exploring those shapes.

Untitled, 24” x 24” x 24”, aluminum

Untitled, 24” x 24” x 24”, aluminum

AAS: Before we jump into talking about more of your sculptures, tell me about your design and construction process.

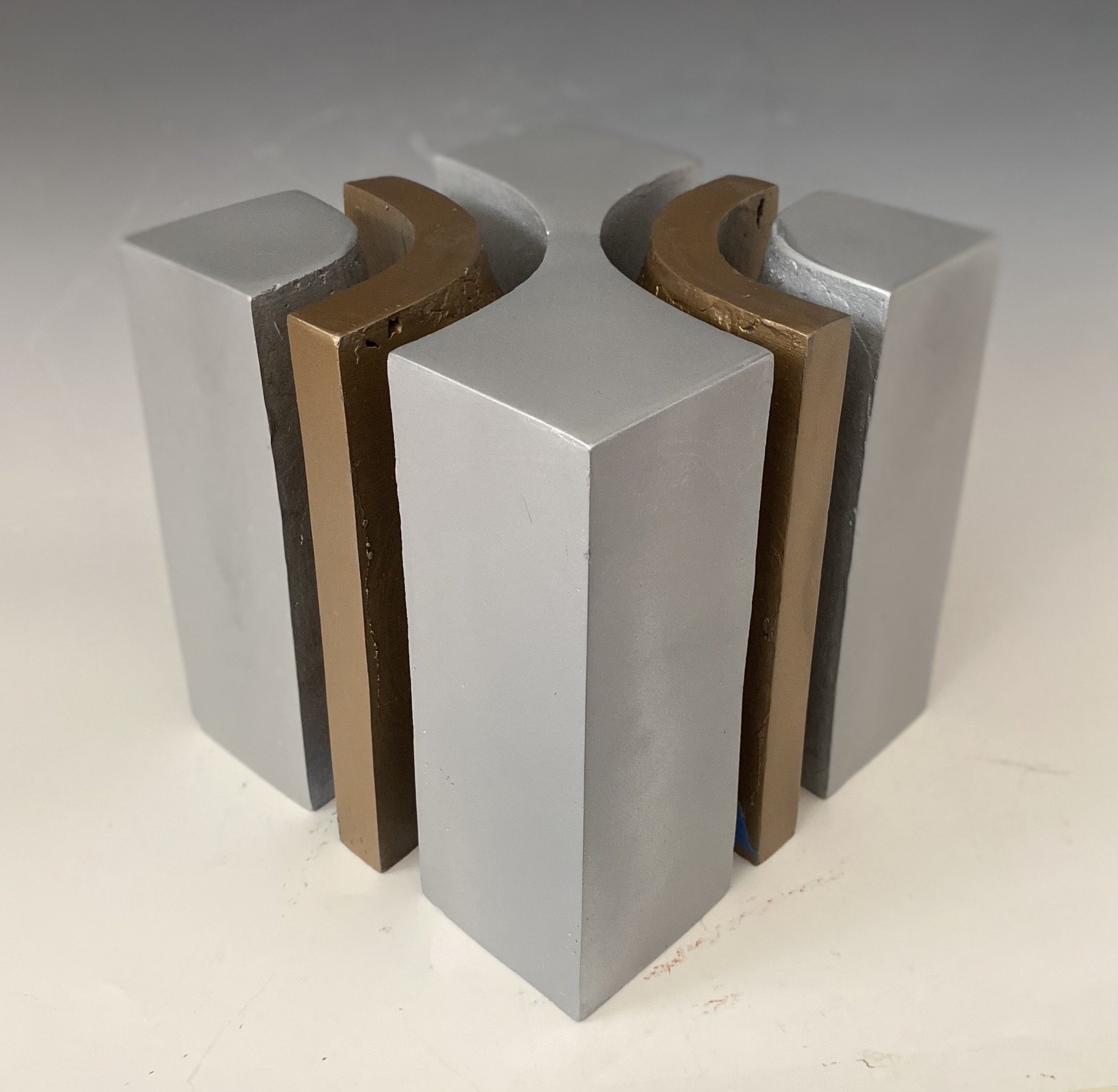

AH: I worked for years with a sculptor in Philly named Robin Fredenthal. He had Parkinson’s and was unable to fabricate models himself. I was the last in a long line of people who fabricated geometry-based models for him. We made hundreds together, all made with cardboard, scotch tape and drafting tools. My work now is mostly model making but using 3d printers and laser cutters to speed up the process. I was always frustrated but the time it took to render each permutation of an idea, now I can pretty much keep up with ideas being generated with each iteration. When a model starts to look like a candidate to be rendered in a more permanent material, I generally increase the scale a bit and focus on the practical reality of whatever process I have at my disposal. At different times in my life, I’ve had access to tools that do a specific job, and I use the materials and fabrication process available to fabricate different work with those specific tools.

Laser carver

3D printer

At Hendrix, we have a small foundry on campus, with that I can cast bronze and aluminum. I have a collection of 3D printers. I can quickly create variations of a form I’m working on, and because the filament a printer uses has a melting point of about 200 degrees, I can use those models the same way you would use wax in the lost wax process of casting. That method of casting has been around for about 2,500 years. It’s amazing that I have robots that can fabricate models in a material than then can be used to cast metal directly from the model. Throughout the history of art, the work created has always reflected the latest technology of the times. There is no doubt my work was created in the early 20th century. The laser is also handy when creating iterations of an idea. It can cut a variety of thin cardboard, plywood, leather, rubber, plexiglass – whatever materials I have on hand to make models with. Anything I create on the small laser can be cut on a water jet cutter. This is a machine that can cut aluminum up to 6” thick or so and will accept a 4’ x 10’ sheet of material, with precision. I am creating new sculptures using 1/4” thick aluminum with this machine right now.

AAS: You created this very cool-looking lamp. How was it constructed?

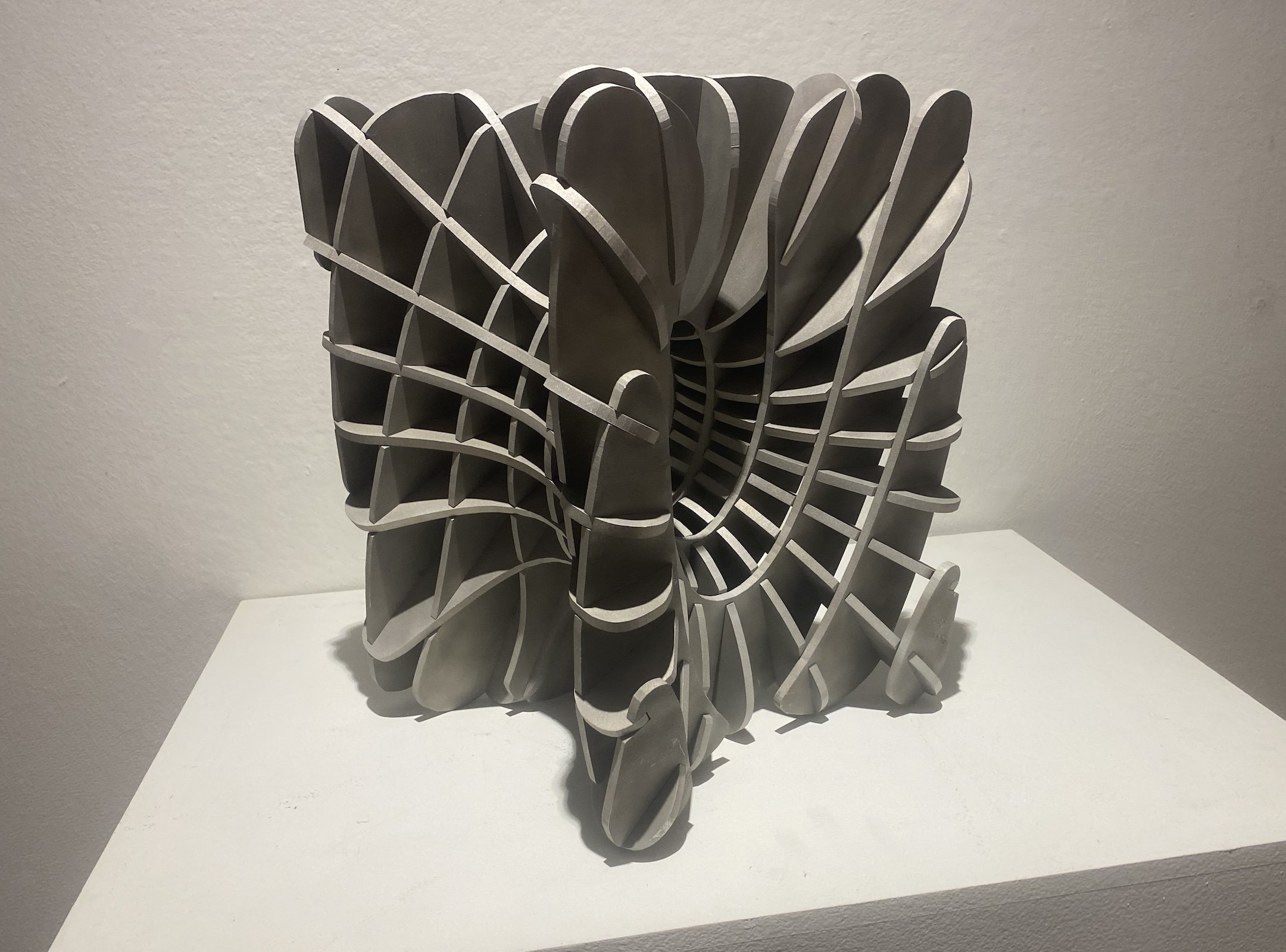

Lamp, 15” diameter, polylactic acid printing

AH: That lamp was the result of playing with a new computer rendering program and trying to see what my printer was capable of creating. The challenge with that piece was to create a grid that would obscure the lightbulb, but allow light to shine through, and to create it without adding supports during the fabrication. If the object you are printing has any overhang, you have to add a support structure in the program so that the printer doesn’t just start squirting material into space and messing up your print. This piece is all overhang, but designed in a way that doesn’t require support. Supports cause surface blemishes on the object and can look awful. It also increases the amount of material you use and slows down the printing. That lamp took two and a half weeks to print.

AAS: I like that your work combines math and engineering with design. Is it a challenge convincing your students that they must be willing to appreciate and learn the role of math and engineering in the creation of fabricated sculptures?

AH: It’s only a challenge if you tell them it’s math. There are a number of rendering programs that are designed for beginners that I use in the classroom, and my students are creating work within minutes of being introduced to them. All geometry can be described mathematically, but also can be examined and played with in a very sophisticated way by following simple rules using simple tools. The Greeks used a compass and a straight edge to discover most of what we know about solid geometry. I am basically doing the same thing – no math required, just simple tools.

AAS: You created an extraordinary sculpture, which hangs in the lobby of the Art Building at Hendrix College. Tell me about its construction and inspiration.

AH: The piece is a series of rhombicuboctahdra surrounding a dodecahedron. That’s a fancy way of saying I was looking for a form that could be cut using only 90° angles. I had plywood and a router at the time, and I wanted to work with polyhedra, but didn’t want to have to cut complicated angles. This piece only required cutting material at a 45° or 90° angle. I still marvel at the complexity that was derived from such simple shapes. Its inspiration was based on pieces I had explored before. All my work is connected to the work that’s come before. Each piece I make is part of a continuum, they are all related.

Rhombicuboctoheri at the Art Complex A, Hendrix College

Rhombicuboctoheri at the Art Complex A, Hendrix College, 10’ x 10’ x 8’, walnut plywood

AAS: You also have a large sculpture on the campus of the UALR Little Rock. Was that a commissioned piece?

Vintage Plasma on the campus of UCA, 12’ x 8’ x 8’, steel

AH: I was commissioned to make a piece for a patron and ended up making two. One of the pieces was shown in The Delta Exhibition years ago. A professor at UALR saw the second, larger piece and suggested a way we could install it on the UALR campus. I had the piece appraised so that a value could be established for tax purposes and my patron donated it to UALR for the tax write-off. I think that process ruffled a few feathers among faculty and staff over there and I heard that now there is a committee that approves such things. It was looking a tired, so last summer I snuck over there and repainted it one day. I suppose I’ll do that every few years now.

AAS: You do a lot of work in cast aluminum including elongated forms that make me think of germinating seeds. Tell me about that form and are there particular limitations or advantages to casting in aluminum?

Untitled, 15” x 4” x 4”, aluminum

AH: That form is just the result of playing with a combination of parametric surfaces. A parametric surface is a kind of surface with shape but no thickness. I can upload an equation to the computer and play with it in different ways, adding thickness, distorting the object, creating holes or different types of surfacing…the more sophisticated the program, the more interesting things I can do to the surface. In most cases I’m not trying to make a seed pod or any recognizable thing, I’m trying to create things that have never existed before. The poet Allan Ginsberg once said, “Things are symbols of themselves.” I agree with him. I’m not a fan of titles, I use them to identify objects for myself, but I would prefer the viewer engage with the work without any prompting. I am trying to make work that is interesting and engaging from all points of view so as you move around the piece the structure is very dynamic. If you are engaged with the object, you could probably interpret it in many ways, but at its core, the work is a simple parametric surface. I’ve been using a lot of aluminum in my work lately because of safety and cost (aluminum pours about 1,000°F cooler than bronze, and is a lot cheaper), but primarily I use aluminum because it is a contemporary material. Aluminum was not a common material until the 1930’s, so any future archeologist can easily date the work based on material alone. Bronze as a material carries so much baggage with it, having been in use for over 2,500 years. I see no reason to compete with that when other materials are available now.

AAS: So many of the artists I’ve interviewed are graduates of art programs at Hendrix and UCA. What do you think the art students that you teach are most interested in and most worried about these days?

AH: Most students seem to be exploring self and identity. It’s really not much different from when I was in their position 40 years ago. I think it’s just a process all artists go through when they begin to get serious about creating. Some continue it throughout life, while others find their voice in other ways. Hendrix is a small liberal arts college, and students are required to take a class in the arts to fulfill their degree requirements. Besides sculpture and ceramics, Hendrix College of Art offers photography, painting/drawing and printmaking, taught by professors who are practicing artists themselves. We are also offering Digital Arts as an area of study in all disciplines. It’s the perfect place for students to discover their inner artist. Because we are a small college, students receive a lot of personal attention from faculty. No matter what genre students chooses to explore, they have the opportunity to use the arts as an outlet for personal expression.